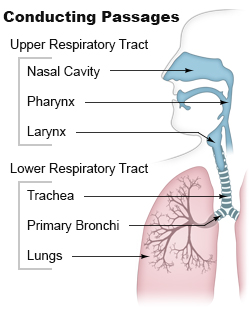

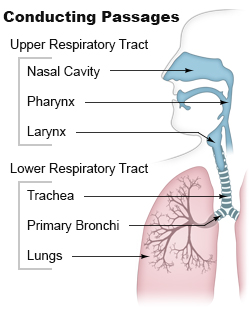

Tracheal intubation, usually simply referred to as intubation, is the placement of a flexible plastic tube into the trachea (windpipe) to maintain an open airway or to serve as a conduit through which to administer certain drugs. It is frequently performed in critically injured, ill, or anesthetized patients to facilitate ventilation of the lungs, including mechanical ventilation, and to prevent the possibility of asphyxiation or airway obstruction.

Pulmonary aspiration is the entry of solid or liquid material such as pharyngeal secretions, food, drink, or stomach contents from the oropharynx or gastrointestinal tract, into the trachea and lungs. When pulmonary aspiration occurs during eating and drinking, the aspirated material is often colloquially referred to as "going down the wrong pipe".

Pulmonology, pneumology or pneumonology is a medical specialty that deals with diseases involving the respiratory tract. It is also known as respirology, respiratory medicine, or chest medicine in some countries and areas.

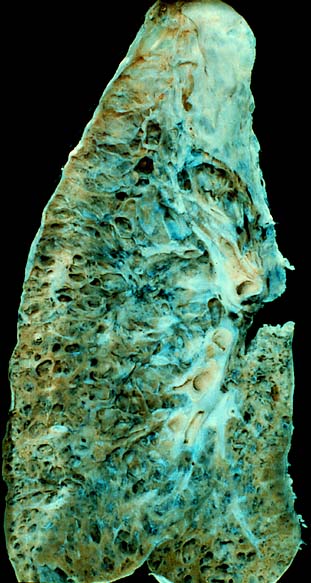

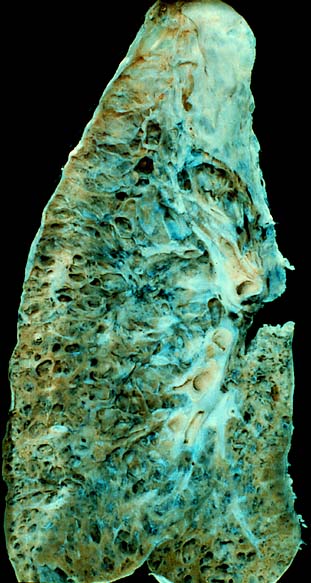

Interstitial lung disease (ILD), or diffuse parenchymal lung disease (DPLD), is a group of respiratory diseases affecting the interstitium and space around the alveoli of the lungs. It concerns alveolar epithelium, pulmonary capillary endothelium, basement membrane, and perivascular and perilymphatic tissues. It may occur when an injury to the lungs triggers an abnormal healing response. Ordinarily, the body generates just the right amount of tissue to repair damage, but in interstitial lung disease, the repair process is disrupted, and the tissue around the air sacs (alveoli) becomes scarred and thickened. This makes it more difficult for oxygen to pass into the bloodstream. The disease presents itself with the following symptoms: shortness of breath, nonproductive coughing, fatigue, and weight loss, which tend to develop slowly, over several months. The average rate of survival for someone with this disease is between three and five years. The term ILD is used to distinguish these diseases from obstructive airways diseases.

Laryngeal papillomatosis, also known as recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) or glottal papillomatosis, is a rare medical condition in which benign tumors (papilloma) form along the aerodigestive tract. There are two variants based on the age of onset: juvenile and adult laryngeal papillomatosis. The tumors are caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection of the throat. The tumors may lead to narrowing of the airway, which may cause vocal changes or airway obstruction. Laryngeal papillomatosis is initially diagnosed through indirect laryngoscopy upon observation of growths on the larynx and can be confirmed through a biopsy. Treatment for laryngeal papillomatosis aims to remove the papillomas and limit their recurrence. Due to the recurrent nature of the virus, repeated treatments usually are needed. Laryngeal papillomatosis is primarily treated surgically, though supplemental nonsurgical and/or medical treatments may be considered in some cases. The evolution of laryngeal papillomatosis is highly variable. Though total recovery may be observed, it is often persistent despite treatment. The number of new cases of laryngeal papillomatosis cases is approximately 4.3 cases per 100,000 children and 1.8 cases per 100,000 adults annually.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) or extrinsic allergic alveolitis (EAA) is a syndrome caused by the repetitive inhalation of antigens from the environment in susceptible or sensitized people. Common antigens include molds, bacteria, bird droppings, bird feathers, agricultural dusts, bioaerosols and chemicals from paints or plastics. People affected by this type of lung inflammation (pneumonitis) are commonly exposed to the antigens by their occupations, hobbies, the environment and animals. The inhaled antigens produce a hypersensitivity immune reaction causing inflammation of the airspaces (alveoli) and small airways (bronchioles) within the lung. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis may eventually lead to interstitial lung disease.

Pneumonitis describes general inflammation of lung tissue. Possible causative agents include radiation therapy of the chest, exposure to medications used during chemo-therapy, the inhalation of debris, aspiration, herbicides or fluorocarbons and some systemic diseases. If unresolved, continued inflammation can result in irreparable damage such as pulmonary fibrosis.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) refers to pneumonia contracted by a person outside of the healthcare system. In contrast, hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is seen in patients who have recently visited a hospital or who live in long-term care facilities. CAP is common, affecting people of all ages, and its symptoms occur as a result of oxygen-absorbing areas of the lung (alveoli) filling with fluid. This inhibits lung function, causing dyspnea, fever, chest pains and cough.

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), formerly known as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP), is an inflammation of the bronchioles (bronchiolitis) and surrounding tissue in the lungs. It is a form of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia.

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a type of lung infection that occurs in people who are on mechanical ventilation breathing machines in hospitals. As such, VAP typically affects critically ill persons that are in an intensive care unit (ICU) and have been on a mechanical ventilator for at least 48 hours. VAP is a major source of increased illness and death. Persons with VAP have increased lengths of ICU hospitalization and have up to a 20–30% death rate. The diagnosis of VAP varies among hospitals and providers but usually requires a new infiltrate on chest x-ray plus two or more other factors. These factors include temperatures of >38 °C or <36 °C, a white blood cell count of >12 × 109/ml, purulent secretions from the airways in the lung, and/or reduction in gas exchange.

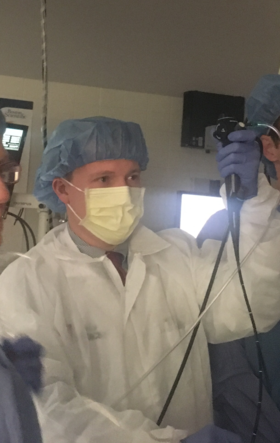

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), also known as bronchoalveolar washing, is a diagnostic method of the lower respiratory system in which a bronchoscope is passed through the mouth or nose into an appropriate airway in the lungs, with a measured amount of fluid introduced and then collected for examination. This method is typically performed to diagnose pathogenic infections of the lower respiratory airways, though it also has been shown to have utility in diagnosing interstitial lung disease. Bronchoalveolar lavage can be a more sensitive method of detection than nasal swabs in respiratory molecular diagnostics, as has been the case with SARS-CoV-2 where bronchoalveolar lavage samples detect copies of viral RNA after negative nasal swab testing.

Williams–Campbell syndrome (WCS) is a disease of the airways where cartilage in the bronchi is defective. It is a form of congenital cystic bronchiectasis. This leads to collapse of the airways and bronchiectasis. It acts as one of the differential to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. WCS is a deficiency of the bronchial cartilage distally.

Pulmonary hygiene, also referred to as pulmonary toilet, is a set of methods used to clear mucus and secretions from the airways. The word pulmonary refers to the lungs. The word toilet, related to the French toilette, refers to body care and hygiene; this root is used in words such as toiletry that also relate to cleansing.

Tracheobronchial injury is damage to the tracheobronchial tree. It can result from blunt or penetrating trauma to the neck or chest, inhalation of harmful fumes or smoke, or aspiration of liquids or objects.

Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (ENB) is a medical procedure utilizing electromagnetic technology designed to localize and guide endoscopic tools or catheters through the bronchial pathways of the lung. Using a virtual, three-dimensional (3D) bronchial map from a recently computed tomography (CT) chest scan and disposable catheter set, physicians are able to navigate to a desired location within the lung to biopsy lesions, stage lymph nodes, insert markers to guide radiotherapy or guide brachytherapy catheters.

Foreign body aspiration occurs when a foreign body enters the airway which can cause difficulty breathing or choking. Objects may reach the respiratory tract and the digestive tract from the mouth and nose, but when an object enters the respiratory tract it is termed aspiration. The foreign body can then become lodged in the trachea or further down the respiratory tract such as in a bronchus. Regardless of the type of object, any aspiration can be a life-threatening situation and requires timely recognition and action to minimize risk of complications. While advances have been made in management of this condition leading to significantly improved clinical outcomes, there were still 2,700 deaths resulting from foreign body aspiration in 2018. Approximately one child dies every five days due to choking on food in the United States, highlighting the need for improvements in education and prevention.

A double-lumen endotracheal tube is a type of endotracheal tube which is used in tracheal intubation during thoracic surgery and other medical conditions to achieve selective, one-sided ventilation of either the right or the left lung.

Advanced airway management is the subset of airway management that involves advanced training, skill, and invasiveness. It encompasses various techniques performed to create an open or patent airway – a clear path between a patient's lungs and the outside world.

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP) is an uncommon, acute-onset form of eosinophilic lung disease which varies in severity. Though poorly understood, the pathogenesis of AEP likely varies depending on the underlying cause which may include smoking, inhalation exposure, medication, and infection. In most patients, AEP is idiopathic, or has no known cause.

Interventional pulmonology is a maturing medical sub-specialty from its parent specialty of pulmonary medicine. It deals specifically with minimally invasive endoscopic and percutaneous procedures for diagnosis and treatment of neoplastic as well as non-neoplastic diseases of the airways, lungs, and pleura. Many IP procedures constitute efficacious yet less invasive alternatives to thoracic surgery.