The pleural cavity, pleural space, or interpleural space is the potential space between the pleurae of the pleural sac that surrounds each lung. A small amount of serous pleural fluid is maintained in the pleural cavity to enable lubrication between the membranes, and also to create a pressure gradient.

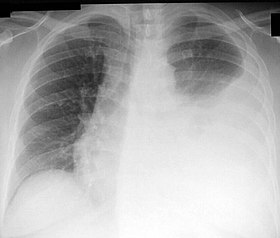

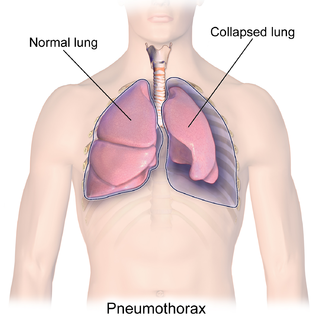

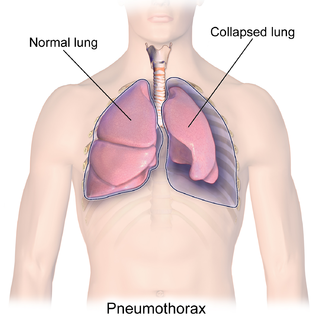

A pneumothorax is an abnormal collection of air in the pleural space between the lung and the chest wall. Symptoms typically include sudden onset of sharp, one-sided chest pain and shortness of breath. In a minority of cases, a one-way valve is formed by an area of damaged tissue, and the amount of air in the space between chest wall and lungs increases; this is called a tension pneumothorax. This can cause a steadily worsening oxygen shortage and low blood pressure. This leads to a type of shock called obstructive shock, which can be fatal unless reversed. Very rarely, both lungs may be affected by a pneumothorax. It is often called a "collapsed lung", although that term may also refer to atelectasis.

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other symptoms may include shortness of breath, cough, fever, or weight loss, depending on the underlying cause. Pleurisy can be caused by a variety of conditions, including viral or bacterial infections, autoimmune disorders, and pulmonary embolism.

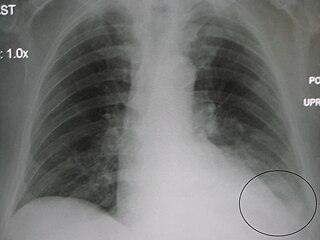

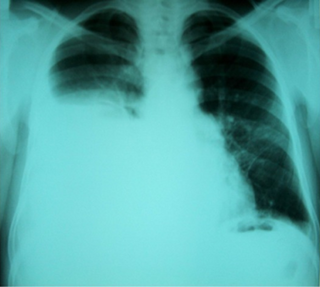

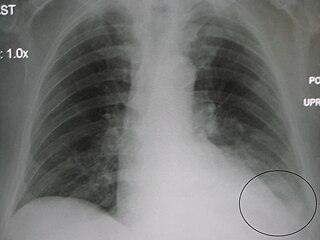

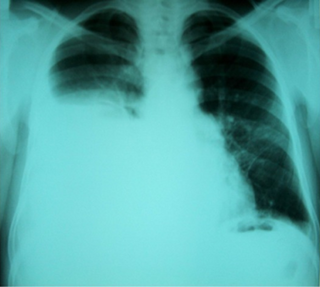

A pleural effusion is accumulation of excessive fluid in the pleural space, the potential space that surrounds each lung. Under normal conditions, pleural fluid is secreted by the parietal pleural capillaries at a rate of 0.6 millilitre per kilogram weight per hour, and is cleared by lymphatic absorption leaving behind only 5–15 millilitres of fluid, which helps to maintain a functional vacuum between the parietal and visceral pleurae. Excess fluid within the pleural space can impair inspiration by upsetting the functional vacuum and hydrostatically increasing the resistance against lung expansion, resulting in a fully or partially collapsed lung.

An exudate is a fluid released by an organism through pores or a wound, a process known as exuding or exudation. Exudate is derived from exude 'to ooze' from Latin exsūdāre 'to sweat'.

Pericardiocentesis (PCC), also called pericardial tap, is a medical procedure where fluid is aspirated from the pericardium.

A chest tube is a surgical drain that is inserted through the chest wall and into the pleural space or the mediastinum in order to remove clinically undesired substances such as air (pneumothorax), excess fluid, blood (hemothorax), chyle (chylothorax) or pus (empyema) from the intrathoracic space. An intrapleural chest tube is also known as a Bülau drain or an intercostal catheter (ICC), and can either be a thin, flexible silicone tube, or a larger, semi-rigid, fenestrated plastic tube, which often involves a flutter valve or underwater seal.

A hemothorax is an accumulation of blood within the pleural cavity. The symptoms of a hemothorax may include chest pain and difficulty breathing, while the clinical signs may include reduced breath sounds on the affected side and a rapid heart rate. Hemothoraces are usually caused by an injury, but they may occur spontaneously due to cancer invading the pleural cavity, as a result of a blood clotting disorder, as an unusual manifestation of endometriosis, in response to Pneumothorax, or rarely in association with other conditions.

Hydrothorax is the synonym of pleural effusion in which fluid accumulates in the pleural cavity. This condition is most likely to develop secondary to congestive heart failure, following an increase in hydrostatic pressure within the lungs. More rarely, hydrothorax can develop in 10% of patients with ascites which is called hepatic hydrothorax. It is often difficult to manage in end-stage liver failure and often fails to respond to therapy.

A chylothorax is an abnormal accumulation of chyle, a type of lipid-rich lymph, in the space surrounding the lung. The lymphatics of the digestive system normally returns lipids absorbed from the small bowel via the thoracic duct, which ascends behind the esophagus to drain into the left brachiocephalic vein. If normal thoracic duct drainage is disrupted, either due to obstruction or rupture, chyle can leak and accumulate within the negative-pressured pleural space. In people on a normal diet, this fluid collection can sometimes be identified by its turbid, milky white appearance, since chyle contains emulsified triglycerides.

Paracentesis is a form of body fluid sampling procedure, generally referring to peritoneocentesis in which the peritoneal cavity is punctured by a needle to sample peritoneal fluid.

Lung abscess is a type of liquefactive necrosis of the lung tissue and formation of cavities containing necrotic debris or fluid caused by microbial infection.

Transudate is extravascular fluid with low protein content and a low specific gravity. It has low nucleated cell counts and the primary cell types are mononuclear cells: macrophages, lymphocytes and mesothelial cells. For instance, an ultrafiltrate of blood plasma is transudate. It results from increased fluid pressures or diminished colloid oncotic forces in the plasma.

A pericardial effusion is an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the pericardial cavity. The pericardium is a two-part membrane surrounding the heart: the outer fibrous connective membrane and an inner two-layered serous membrane. The two layers of the serous membrane enclose the pericardial cavity between them. This pericardial space contains a small amount of pericardial fluid, normally 15-50 mL in volume. The pericardium, specifically the pericardial fluid provides lubrication, maintains the anatomic position of the heart in the chest, and also serves as a barrier to protect the heart from infection and inflammation in adjacent tissues and organs.

A parapneumonic effusion is a type of pleural effusion that arises as a result of a pneumonia, lung abscess, or bronchiectasis. There are three types of parapneumonic effusions: uncomplicated effusions, complicated effusions, and empyema. Uncomplicated effusions generally respond well to appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Malignant pleural effusion is a condition in which cancer causes an abnormal amount of fluid to collect between the thin layers of tissue (pleura) lining the outside of the lung and the wall of the chest cavity. Lung cancer and breast cancer account for about 50-65% of malignant pleural effusions. Other common causes include pleural mesothelioma and lymphoma.

A thoracostomy is a small incision of the chest wall, with maintenance of the opening for drainage. It is most commonly used for the treatment of a pneumothorax. This is performed by physicians, paramedics, and nurses usually via needle thoracostomy or an incision into the chest wall with the insertion of a thoracostomy tube or with a hemostat and the provider's finger.

Pleural disease occurs in the pleural space, which is the thin fluid-filled area in between the two pulmonary pleurae in the human body. There are several disorders and complications that can occur within the pleural area, and the surrounding tissues in the lung.

Obstructive shock is one of the four types of shock, caused by a physical obstruction in the flow of blood. Obstruction can occur at the level of the great vessels or the heart itself. Causes include pulmonary embolism, cardiac tamponade, and tension pneumothorax. These are all life-threatening. Symptoms may include shortness of breath, weakness, or altered mental status. Low blood pressure and tachycardia are often seen in shock. Other symptoms depend on the underlying cause.

Hepatic hydrothorax is a rare form of pleural effusion that occurs in people with liver cirrhosis. It is defined as an effusion of over 500 mL in people with liver cirrhosis that is not caused by heart, lung, or pleural disease. It is found in 5–10% of people with liver cirrhosis and 2–3% of people with pleural effusions. It is much more common on the right side, with 85% of cases occurring on the right, 13% on the left, and 2% on both. Although it is most common in people with severe ascites, it can also occur in people with mild or no ascites. Symptoms are not specific and mostly involve the respiratory system.