With the use of high magnification ... one can almost always isolate the used portion of the tool and reconstruct its movement during use, as well as, in the majority of cases, determine exactly which material was being worked.

— Lawrence H. Keeley, Experimental Determination of Stone Tool Uses: A Microwear Analysis (1980), p.78.

Keeley's most noted contribution to the fields of Paleolithic archaeology and experimental archaeology was his development and defense of microwear analysis in the study of stone tools and hominid behavioral reconstruction. [6] Microwear analysis is one of two primary methods (the other being use-wear analysis) for identifying the functions of artifact tools. Both methods rely on examination of the smoothed down sections of blades, called "polishes," formed on the working edges of lithics. Microwear differs from use-wear because of the scale at which the analysis happens; microwear analysis is the use of microscopy to evaluate and understand these polishes. [7] Keeley is considered to be a pioneer of microwear analysis, and microwear analysis has become a vital method of archaeological research. [8] [3]

The primary way that Keeley demonstrated the efficacy of microwear analysis was through the Keeley–Newcomer blind test. [5] The methodology of this test was similar to other early microwear experiments, and it consisted of attempting to correctly determine tool function from analysis of lithics made and used by a researcher. The Keeley-Newcomer test differed from prior tests though because the tools were made and used by a researcher, Mark Newcomer, independent of the archaeologist, Lawrence Keeley. Keeley took up this test as a challenge from Mark Newcomer, a lecturer at London University's Institute of Archaeology and a skeptic of microwear analysis, to demonstrate the reliability of the method. [9] Running a blind test granted their results objectivity and turned the experiment into an argument for the general use of microwear analysis in archaeological research. As a result of these original results and similar tests, microwear has enjoyed consistent use and development across the field of Paleolithic archaeology since 1977. [3] [10]

Despite Keeley's successful identification of the majority of the lithics provided by Newcomer and subsequent similar blind tests by other archaeologists, Newcomer wrote critically of microwear analysis in 1986. He wrote of a series of blind tests run by London University, "there has been no convincing demonstration that anyone can consistently identify worked materials by polish type alone." [11] However, other archaeologists have defended Keeley's contribution and even criticized Newcomer's skepticism. [12] [13]

Koobi Fora study

Keeley worked with Nicholas Toth in 1981 to analyze oldowan tools from Koobi Fora, Kenya. Using microwear and use-wear analysis, the pair narrowed their research to 54 lithic flakes from among the oldowan, which they used to understand the at least 1.4 million year-old civilization. Nine of these 54 exhibited signs of wear in their analysis, which involved high power microscopy at 50-400x magnification. [14] Keeley discovered that these nine flakes, which would have been overlooked by most traditional studies, were actually used as stone tools themselves and were not simply debitage from the creation of lithic cores. [15] Their conclusion was that flakes themselves were the desired tool in lithic reduction, which was supported by their identification of flakes used for butchery, woodworking, and standard cutting of plant matter. [16] At the time of publishing, this use theory ran counter to a competing theory that lithic cores were the primary intended tools. [17] Since publishing, however, their theories have become widely known and have found support in several other studies. Their joint study was published in Nature and has been widely cited as an example of hominid behavioral reconstruction. [5]

Toth later hypothesized that these flake tools were likely to have initially been created accidentally from the creation of cores but later became the desired result instead of cores. He also stated that the development of flake tools was crucial in the evolution of human intelligence, a theory that has found support even outside of archaeology. [7] [18] [19]

War Before Civilization

Keeley's best known work is War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage, published by the Oxford University Press in 1996. This book was an empirical rebuttal of the popular romantic anthropological idea of the "noble savage." [4] Keeley's core thesis is that western academics had "pacified" history, especially relating to the role of violence in the history of human development, and that overall death rates in modern societies were remarkably lower than among small-scale Paleolithic groups. War Before Civilization reinvigorated classic arguments regarding human nature, largely inspired by Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau's perspectives on the subject. This book also initiated a renewed interdisciplinary interest in war in the context of sociocultural evolution, which lasted through the latter 1990s. [20] [21] [22]

The findings of this book have been the subject of some criticism, including a short 2014 article reprinted by Indian Country Today. [23] Keith F. Otterbein, an anthropology professor, criticized Keeley's book in American Anthropologist , explaining that Keeley was right to identify two competing theories on human nature, but that he did not capture the full scope of historical developments by disregarding the idea of peaceful prehistoric hominids. Neil L. Whitehead, another notable anthropologist and someone identified by Keeley[ citation needed ] as a proponent of the myth of the peaceful savage, sympathized with Otterbein but saw other ways to challenge Keeley's "peculiar view" of anthropology. [24] [25]

Books

- Experimental Determination of Stone Tool Uses: A Microwear Analysis (University of Chicago Press, 1980); ISBN 978-0226428895

- War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage (Oxford University Press, 1996); ISBN 978-0195091120

Related Research Articles

In archaeology, in particular of the Stone Age, lithic reduction is the process of fashioning stones or rocks from their natural state into tools or weapons by removing some parts. It has been intensely studied and many archaeological industries are identified almost entirely by the lithic analysis of the precise style of their tools and the chaîne opératoire of the reduction techniques they used.

In archaeology, lithic analysis is the analysis of stone tools and other chipped stone artifacts using basic scientific techniques. At its most basic level, lithic analyses involve an analysis of the artifact's morphology, the measurement of various physical attributes, and examining other visible features.

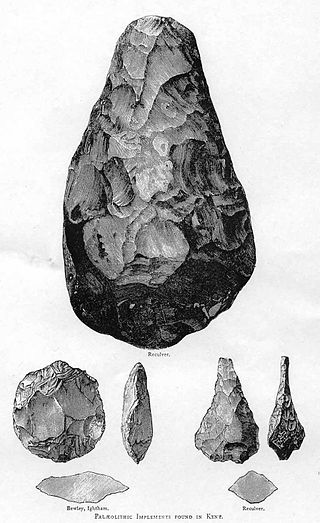

A hand axe is a prehistoric stone tool with two faces that is the longest-used tool in human history. It is made from stone, usually flint or chert that has been "reduced" and shaped from a larger piece by knapping, or hitting against another stone. They are characteristic of the lower Acheulean and middle Palaeolithic (Mousterian) periods, roughly 1.6 million years ago to about 100,000 years ago, and used by Homo erectus and other early humans, but rarely by Homo sapiens.

The Oldowan was a widespread stone tool archaeological industry (style) in prehistory. These early tools were simple, usually made with one or a few flakes chipped off with another stone. Oldowan tools were used during the Lower Paleolithic period, 2.9 million years ago up until at least 1.7 million years ago (Ma), by ancient Hominins across much of Africa. This technological industry was followed by the more sophisticated Acheulean industry.

In archaeology, a denticulate tool is a stone tool containing one or more edges that are worked into multiple notched shapes, much like the toothed edge of a saw. Such tools have been used as saws for woodworking, processing meat and hides, craft activities and for agricultural purposes. Denticulate tools were used by many different groups worldwide and have been found at a number of notable archaeological sites. They can be made from a number of different lithic materials, but a large number of denticulate tools are made from flint.

In archaeology, a blade is a type of stone tool created by striking a long narrow flake from a stone core. This process of reducing the stone and producing the blades is called lithic reduction. Archaeologists use this process of flintknapping to analyze blades and observe their technological uses for historical purposes.

The Levallois technique is a name given by archaeologists to a distinctive type of stone knapping developed around 250,000 to 300,000 years ago during the Middle Palaeolithic period. It is part of the Mousterian stone tool industry, and was used by the Neanderthals in Europe and by modern humans in other regions such as the Levant.

In archaeology, lithic technology includes a broad array of techniques used to produce usable tools from various types of stone. The earliest stone tools to date have been found at the site of Lomekwi 3 (LOM3) in Kenya and they have been dated to around 3.3 million years ago. The archaeological record of lithic technology is divided into three major time periods: the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic. Not all cultures in all parts of the world exhibit the same pattern of lithic technological development, and stone tool technology continues to be used to this day, but these three time periods represent the span of the archaeological record when lithic technology was paramount. By analysing modern stone tool usage within an ethnoarchaeological context, insight into the breadth of factors influencing lithic technologies in general may be studied. See: Stone tool. For example, for the Gamo of Southern Ethiopia, political, environmental, and social factors influence the patterns of technology variation in different subgroups of the Gamo culture; through understanding the relationship between these different factors in a modern context, archaeologists can better understand the ways that these factors could have shaped the technological variation that is present in the archaeological record.

Use-wear analysis is a method in archaeology to identify the functions of artifact tools by closely examining their working surfaces and edges. It is mainly used on stone tools, and is sometimes referred to as "traceological analysis".

In archaeology, debitage is all the material produced during the process of lithic reduction – the production of stone tools and weapons by knapping stone. This assemblage may include the different kinds of lithic flakes and lithic blades, but most often refers to the shatter and production debris, and production rejects.

The Klasies River Caves are a series of caves located east of the Klasies River Mouth on the Tsitsikamma coast in the Humansdorp district of Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. The Klasies River Main (KRM) site consists of 3 main caves and 2 shelters located within a cliff on the southern coast of the Eastern Cape. The site provides evidence for developments in stone tool technology, evolution of modern human anatomy and behavior, and changes in paleoecology and climate in Southern Africa based on evidence from plant remains.

Harold Lewis Dibble was an American Paleolithic archaeologist. His main research concerned the lithic reduction during which he conducted fieldwork in France, Egypt, and Morocco. He was a professor of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania and Curator-in-Charge of the European Section of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Howiesons Poort is a technological and cultural period characterized by material evidence with shared design features found in South Africa, Lesotho, and Namibia. It was named after the Howieson's Poort Shelter archaeological site near Grahamstown in South Africa, where the first assemblage of these tools was discovered. Howiesons Poort is believed, based on chronological comparisons between many sites, to have started around 64.8 thousand years ago and ended around 59.5 thousand years ago. It is considered to be a technocomplex, or a cultural period in archaeology classified by distinct and specific technological materials. Howiesons Poort is notable for its relatively complex tools, technological innovations, and cultural objects evidencing symbolic expression. One site in particular, Sibudu Cave, provides one of the key reference sequences for Howiesons Poort. Howiesons Poort assemblages are primarily found at sites south of the Limpopo River.

Qesem cave is a Lower Paleolithic archaeological site near the city of Kafr Qasim in Israel. Early humans were occupying the site by 400,000 until c. 200,000 years ago.

Border Cave is an archaeological site located in the western Lebombo Mountains in Kwazulu-Natal. The rock shelter has one of the longest archaeological records in southern Africa, which spans from the Middle Stone Age to the Iron Age.

Rose Cottage Cave (RCC) is an archaeological site in the Free State, South Africa, situated only a few kilometers away from Ladybrand, close to the Caledon River, on the northern slopes of the Platberg. RCC is an important site because of its long cultural sequence, its roots in modern human behavior, and the movement of early modern humans out of Africa. Rose Cottage is the only site from the Middle Stone Age that can tell us about the behavioral variability of hunter-gatherers during the Late Pleistocene and Holocene. Berry D. Malan excavated the site between 1943 and 1946, shortly followed by Peter B. Beaumont in the early 1960s, and the most recent excavations occurred from 1987 to 1997 by Lyn Wadley and Philip Harper in 1989 under Wadley's supervision. Humans have inhabited Rose Cottage for over 100,000 years throughout the Middle and Later Stone Ages. Site formation and sediment formation processes at Rose Cottage appear to be primarily anthropogenic. Archaeological research focuses primarily on blade technology and tool forms from the Middle Stone Age and the implications of modern human behavior. Structurally, the cave measures more than 6 meters deep and about 20 by 10 meters. A boulder encloses the front, protecting the cave, but allowing a small opening for a skylight and narrow entrances on both the east and west sides.

Nicholas Patrick Toth is an American archaeologist and paleoanthropologist. He is a Professor in the Cognitive Science Program at Indiana University and is a founder and co-director of the Stone Age Institute. Toth's archaeological and experimental research has focused on the stone tool technology of Early Stone Age hominins who produced Oldowan and Acheulean artifacts which have been discovered across Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. He is best known for his experimental work, with Kathy Schick, including their work with the bonobo Kanzi who they taught to make and use simple stone tools similar to those made by our Early Stone Age ancestors.

Gona is a paleoanthropological research area in Ethiopia's Afar Region. Gona is primarily known for its archaeological sites and discoveries of hominin fossils from the Late Miocene, Early Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. Fossils of Ardipithecus and Homo erectus were discovered there. Two of the most significant finds are an Ardipithecus ramidus postcranial skeleton and an essentially complete Homo erectus pelvis. Historically, Gona had the oldest documented Oldowan artifact assemblages. Archaeologists have since found older examples of the Oldowan at other sites. Still, Gona's Oldowan assemblages have been essential to the archaeological understanding of the Oldowan. Gona's Acheulean archaeological sites have helped us understand the beginnings of the Acheulean Industry.

Kathy Diane Schick is an American archaeologist and paleoanthropologist. She is professor emeritus in the Cognitive Science Program at Indiana University and is a founder and co-director of the Stone Age Institute. Schick is most well known for her experimental work in taphonomy as well as her experimental work, with Nicholas Toth, on the stone tool technology of Early Stone Age hominins, including their work with the bonobo Kanzi who they taught to make and use simple stone tools similar to those made by our Early Stone Age ancestors.

Primate archaeology is a field of research established in 2008 that combines research interests and foci from primatology and archaeology. The main aim of primate archaeology is to study behavior of extant and extinct primates and the associated material records. The discipline attempts to move beyond archaeology's anthropocentric perspective by placing the focus on both past and present primate tool use.

References

- 1 2 3 "Deaths: Lawrence Keeley". November 28, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ↑ "Lawrence H. Keeley, PhD" . Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- 1 2 3 Dunmore, Christopher J.; Pateman, Ben; Key, Alastair (March 2018). "A citation network analysis of lithic microwear research" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 91: 33–42. Bibcode:2018JArSc..91...33D. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.01.006.

- 1 2 Renfrew, Colin; Bahn, Paul G (2016). Archaeology: Theories, Methods, and Practice (7th ed.). Thames and Hudson. pp. 220–221. ISBN 9780500292105.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yerkes, Richard (24 July 2019). "Lawrence H. Keeley's contributions to the use of microwear analysis in reconstructions of past human behavior (1972–2017)". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. Department of Anthropology, Ohio State University. 27: 101937. Bibcode:2019JArSR..27j1937Y. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.101937. S2CID 199933153 . Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ↑ Odell, George Hamley (1975). "Micro-Wear in Perspective: A Sympathetic Response to Lawrence H. Keeley". World Archaeology. 7 (2): 226–40. doi:10.1080/00438243.1975.9979635. JSTOR 124041 . Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- 1 2 Toth, Nicholas (April 1987). "The First Technology". Scientific American. 256 (4): 112–121. Bibcode:1987SciAm.256d.112T. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0487-112. ISSN 0036-8733.

- ↑ Shea, John J. (1992). "Lithic microwear analysis in archeology". Evolutionary Anthropology. 1 (4): 143–150. doi:10.1002/evan.1360010407. S2CID 84924296.

- ↑ Keeley, Lawrence H.; Newcomer, Mark H. (1977). "Microwear analysis of experimental flint tools: a test case". Journal of Archaeological Science. 4 (1): 29–62. Bibcode:1977JArSc...4...29K. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(77)90111-X. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ↑ Ollé, Andreu; Borel, Antony; Vergès Bosch, Josep Maria; Sala, Robert (2014). "Scanning Electron and Optical Light Microscopy: two complementary approaches for the understanding and interpretation of usewear and residues on stone tools". Journal of Archaeological Science. 48: 46–59. Bibcode:2014JArSc..48...46B. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.06.031. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ↑ Newcomer, Mark; Grace, R.; Unger-Hamilton, R. (1986). "Investigating microwear polishes with blind tests". Journal of Archaeological Science. 13 (3): 203–217. Bibcode:1986JArSc..13..203N. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(86)90059-2. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ↑ Moss, Emily H. (1987). "A review of "Investigating microwear polishes with blind tests"". Journal of Archaeological Science. 14 (5): 473–481. Bibcode:1987JArSc..14..473M. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(87)90033-1. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ↑ Bamforth, Douglas B. (1988). "Investigating microwear polishes with blind tests: The institute results in context". Journal of Archaeological Science. 15 (1): 11–23. Bibcode:1988JArSc..15...11B. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(88)90015-5. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ↑ Herrygers, Christa (2002). "A Comparative Analysis of Wood Residues on Experimental Stone Tools and Early Stone Age Artifacts: A Koobi Fora Case Study". McNair Scholars Journal. 6 (1).

- ↑ Keeley, Lawrence; Toth, Nicholas (1981). "Microwear polishes on early stone tools from Koobi Fora, Kenya". Nature. 293 (5832): 464–465. Bibcode:1981Natur.293..464K. doi:10.1038/293464a0. S2CID 4233302 . Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ↑ Toth, Nicholas; Schick, Kathy Diane (1986). "The First Million Years: The Archaeology of Protohuman Culture". Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory. 9: 29. JSTOR 20210075.

- ↑ Plummer, Thomas (2004). "Flaked stones and old bones: Biological and cultural evolution at the dawn of technology". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 125 (Supplement 39: Yearbook of Physical Anthropology): 118–164. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20157 . ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 15605391.

- ↑ Toth, Nicholas (1985). "The Oldowan Reassessed: A Close Look at Early Stone Artifacts". Journal of Archaeological Science. 12 (2): 101–120. Bibcode:1985JArSc..12..101T. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(85)90056-1. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ↑ Cousins, Steven D. (2014). "The semiotic coevolution of mind and culture". Culture & Psychology. 20 (2): 160–191. doi:10.1177/1354067X14532331. S2CID 145519137.

- ↑ Lawler, Andrew (2012). "The Battle Over Violence". Science. 336 (6083): 829–830. doi:10.1126/science.336.6083.829. ISSN 1095-9203. JSTOR 41584838. PMID 22605751.

- ↑ Arrow, Holly (2007). "The Sharp End of Altruism". Science. 318 (5850): 581–582. doi:10.1126/science.1150316. ISSN 1095-9203. JSTOR 20051440. PMID 17962546. S2CID 146797279.

- ↑ Thorpe, I. J. N. (2003). "Anthropology, Archaeology, and the Origin of Warfare". World Archaeology. 35 (1): 145–165. doi:10.1080/0043824032000079198. ISSN 1470-1375. JSTOR 3560217. S2CID 54030253.

- ↑ Jacobs, Don / Four Arrows (2014). "The Heart of Everything That Isn't: the Untold Story of Anti-Indianism in Drury and Clavin's Book on Red Cloud". Ict News. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ↑ Whitehead, Neil L. (2000). "A History of Research on Warfare in Anthropology - Reply to Keith Otterbein". American Anthropologist. 102 (4): 834–837. doi:10.1525/aa.2000.102.4.834. ISSN 1548-1433. JSTOR 684206.

- ↑ Otterbein, Keith F. (1999). "A History of Research on Warfare in Anthropology". American Anthropologist. 101 (4): 794–805. doi: 10.1525/aa.1999.101.4.794 . ISSN 1548-1433. JSTOR 684054.

Lawrence H. Keeley | |

|---|---|

| Born | August 24, 1948 Cupertino, California, US |

| Died | October 11, 2017 (aged 69) [1] |

| Occupation | archaeologist |

| Awards | Society for American Archaeology's Award for Excellence in Lithic Studies [2] |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | San Jose State University (B.A., 1970) University of Oregon (M.A., 1972) Oxford University (Ph.D., 1977) |

| Thesis | An experimental study of Microwear traces on selected British Palaeolithic implements (1977) |

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Other | |