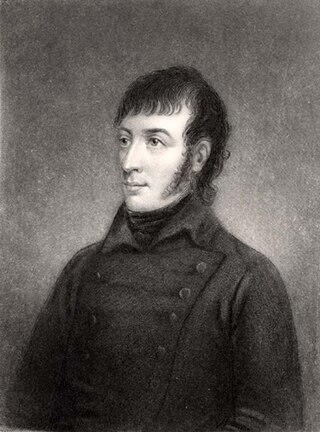

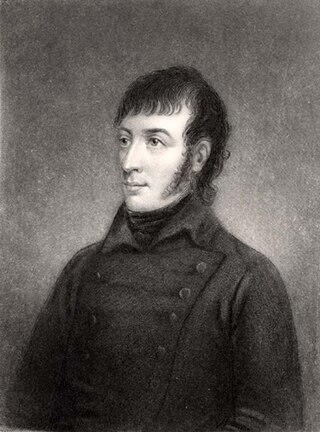

Robert Emmet was an Irish Republican, orator and rebel leader. Following the suppression of the United Irish uprising in 1798, he sought to organise a renewed attempt to overthrow the British Crown and Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland, and to establish a nationally representative government. Emmet entertained, but ultimately abandoned, hopes of immediate French assistance and of coordination with radical militants in Great Britain. In Ireland, many of the surviving veterans of '98 hesitated to lend their support, and his rising in Dublin in 1803 proved abortive.

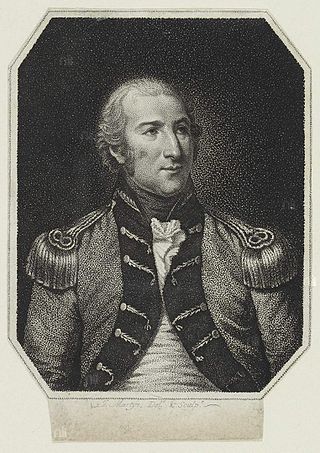

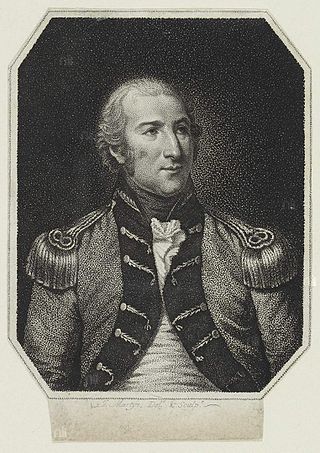

Lord Edward FitzGerald was an Irish aristocrat and nationalist. He abandoned his prospects as a distinguished veteran of British service in the American War of Independence, and as an Irish Parliamentarian, to embrace the cause of an independent Irish republic. Unable to reconcile with Ireland's Protestant Ascendancy or with the Kingdom's English-appointed administration, he sought inspiration in revolutionary France where, in 1792, he met and befriended Thomas Paine. From 1796 he became a leading proponent within the Society of United Irishmen of a French-assisted insurrection. On the eve of the intended uprising in May 1798, he was fatally wounded in the course of arrest.

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association in the Kingdom of Ireland formed in the wake of the French Revolution to secure "an equal representation of all the people" in a national government. Despairing of constitutional reform, and in defiance both of British Crown forces and of Irish sectarian division, in 1798 the United Irishmen instigated a republican rebellion. Their suppression was a prelude to the abolition of the Irish Parliament in Dublin and to Ireland's incorporation in a United Kingdom with Great Britain. An attempt, following the Acts of Union, to revive the movement and renew the insurrection led to an abortive rising in Dublin in 1803.

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 was a major uprising against British rule in Ireland. The main organising force was the Society of United Irishmen, a republican revolutionary group influenced by the ideas of the American and French revolutions: originally formed by Presbyterian radicals angry at being shut out of power by the Anglican establishment, they were joined by many from the majority Catholic population.

William Conyngham Plunket, 1st Baron Plunket, PC (Ire), QC was an Irish politician and lawyer. After gaining public notoriety as the prosecutor in the treason trial of Robert Emmet in 1803, he rose rapidly in government service. He become Lord Chancellor of Ireland in 1830 and served, with a brief interruption, in that post until his retirement in 1841.

Thomas Addis Emmet was an Irish and American lawyer and politician. In Ireland, in the 1790s, he was a senior member of the Society of United Irishmen as it planned for an insurrection against the British Crown and Protestant Ascendancy. In American exile, he took up legal practice in New York, earned a reputation as a staunch abolitionist, and in 1812 to 1813 served as the state's Attorney General.

William Drennan was an Irish physician and writer who moved the formation in Belfast and Dublin of the Society of United Irishmen. He was the author of the Society's original "test" which, in the cause of representative government, committed "Irishmen of every religious persuasion" to a "brotherhood of affection". Drennan had been active in the Irish Volunteer movement and achieved renown with addresses to the public as his "fellow slaves" and to the British Viceroy urging "full and final" Catholic emancipation. After the suppression of the 1798 Rebellion, he sought to advance democratic reform through his continued journalism and through education. With other United Irish veterans, Drennan founded the Belfast [later the Royal Belfast] Academical Institution. As a poet, he is remembered for his eve-of-rebellion When Erin First Rose (1795) with its reference to Ireland as the "Emerald Isle".

Thomas Paliser Russell was a founding member, and leading organiser, of the United Irishmen marked by his radical-democratic and millenarian convictions. A member of the movement's northern executive in Belfast, and a key figure in promoting a republican alliance with the agrarian Catholic Defenders, he was arrested in advance of the risings of 1798 and held until 1802. He was executed in 1803, following Robert Emmet's aborted rising in Dublin for which he had tried, but failed, to raise support among United and Defender veterans in the north.

William Sampson was a lawyer and jurist who in his native Ireland, and in later American exile, identified with the cause of democratic reform. In the 1790s, in Belfast and Dublin he associated with United Irishmen, defending them in Crown prosecutions, contributing to their press and, according to government informants, participating on the eve of rebellion in their inner councils. In New York, from 1806 he won renown as a trial lawyer representing the abolitionist Manumission Society and disputing race as a legal disability; challenging the conspiracy charges against organised labor; and, in the name of religious liberty, establishing Catholic auricular confession as privileged. Maintaining that the tradition of common law denied citizens equal access to the law, and was a systematic source of injustice, Sampson pioneered the American codification movement.

John Keogh was an Irish merchant and political activist. He was a leading campaigner for Catholic Emancipation and reform of the Irish Parliament, active in Dublin on the Catholic Committee and, with some reservation, in the Society of United Irishmen.

Events from the year 1767 in Ireland.

Oliver Bond was an Irish merchant and a member of the Leinster directorate of the Society of United Irishmen. He died in prison following the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

William James MacNeven was an Irish physician forced, as a result of his involvement with insurgent United Irishmen, into exile in the United States where he became a champion of religious and civil liberty and the reputed "father of American chemistry". One of the oldest obelisks in New York City is dedicated to him to the right facing St. Paul's Chapel on Broadway; while to the left stands another obelisk, dedicated to Thomas Emmet, a fellow United Irishman, and Attorney General of New York. MacNeven's monument features a lengthy inscription in Irish, one of the oldest existent dedications of this kind in the Americas.

Henry Charles Sirr was an Anglo-Irish military officer, policeman, merchant and art collector. He played a prominent role in suppressing the Irish Rebellion of 1798, which included personally killing Society of United Irishmen leader Lord Edward FitzGerald, who Sirr alleged had been resisting arrest.

The Irish rebellion of 1803 was an attempt by Irish republicans to seize the seat of the British government in Ireland, Dublin Castle, and trigger a nationwide insurrection. Renewing the struggle of 1798, they were organised under a reconstituted United Irish directorate. Hopes of French aid, of a diversionary rising by radical militants in England, and of Presbyterians in the north-east rallying once more to the cause of a republic were disappointed. The rising in Dublin misfired, and after a series of street skirmishes, the rebels dispersed. Their principal leader, Robert Emmet, was executed; others went into exile.

Peter Finnerty was an Irish printer, publisher, and journalist in both Dublin and London associated with radical, reform and democratic causes. In Dublin, he was a committed United Irishman, but was imprisoned in the course of the 1798 rebellion. In London he was a campaigning reporter for The Morning Chronicle, imprisoned again in 1811 for libel in his condemnation of Lord Castlereagh.

Donnybrook Cemetery is located close to the River Dodder in Donnybrook, Dublin, Ireland. The cemetery was the location of an old Celtic church founded by Saint Broc and later a church dedicated to St. Mary. The site has been in use between 800 and 1880 with the exception of some burial rights.

Samuel Turner (1765–1807) was an Irish barrister, a Protestant supporter of the United Irishmen in Newry who in 1797 escaped to the European continent, changed loyalties, and informed the British and Irish authorities of United Irish activity and personnel in Ireland, Hamburg, and Paris.

"The Lass of Richmond Hill", also known as "The Sweet Lass of Richmond Hill", is a song written by Leonard McNally with music composed by James Hook, and was first publicly performed in 1789. It was said to be a favourite of George III and, at one time, was thought to have been written by his son, George IV. It is a love ballad which popularized the poetic phrase "a rose without a thorn" as a romantic metaphor. Associated with the English town of Richmond in North Yorkshire, it is now often mistakenly considered to be a traditional folk song, and has been assigned the number 1246 on the Roud Folk Song Index. The music is also used as a military march by the British army.

William Putnam McCabe (1776–1821) was an emissary and organiser in Ireland for the insurrectionary Society of United Irishmen. Facing multiple indictments for treason as a result of his role in fomenting the 1798 rebellion, he effected a number of daring escapes but was ultimately forced by his government pursuers into exile in France. With the favour of Napoleon, he established a cotton factory at Rouen while remaining active as a member of a new United Irish Directory. He worked to assist Robert Emmett in coordinating a new rising in Ireland in 1803, and later had contact with the Spencean circle in London implicated in both the Spa Field riots and the Cato Street Conspiracy.