In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the Institutes of Justinian, a codification of Roman Law from the sixth century AD, where justice is defined as "the constant and perpetual will to render to each his due".

Political philosophy, or political theory, is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, justice, liberty, property, rights, law, and authority: what they are, if they are needed, what makes a government legitimate, what rights and freedoms it should protect, what form it should take, what the law is, and what duties citizens owe to a legitimate government, if any, and when it may be legitimately overthrown, if ever.

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based on the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relationships, with a smaller degree of development being placed on individualism. Although the community might be a family, communitarianism usually is understood, in the wider, philosophical sense, as a collection of interactions, among a community of people in a given place, or among a community who share an interest or who share a history. Communitarianism is often contrasted with individualism, and opposes laissez-faire policies that deprioritize the stability of the overall community.

John Bordley Rawls was an American moral, legal and political philosopher in the modern liberal tradition. Rawls has been described as one of the most influential political philosophers of the 20th century.

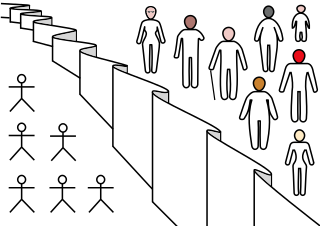

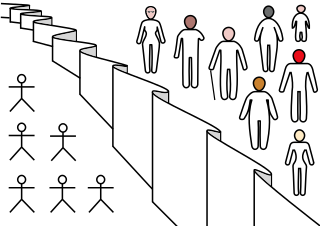

The original position (OP), often referred to as the veil of ignorance, is a thought experiment often associated with the works of American philosopher John Rawls. In the original position, one is asked to consider which principles they would select for the basic structure of society, but they must select as if they had no knowledge ahead of time what position they would end up having in that society. This choice is made from behind a "veil of ignorance", which prevents them from knowing their ethnicity, social status, gender, and their or anyone else's ideas of how to lead a good life. Ideally, this would force participants to select principles impartially and rationally.

Richard McKay Rorty was an American philosopher and historian of ideas. Educated at the University of Chicago and Yale University, Rorty's academic career included appointments as the Stuart Professor of Philosophy at Princeton University, the Kenan Professor of Humanities at the University of Virginia, and as a professor of comparative literature at Stanford University. Among his most influential books are Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979), Consequences of Pragmatism (1982), and Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989).

A Theory of Justice is a 1971 work of political philosophy and ethics by the philosopher John Rawls (1921–2002) in which the author attempts to provide a moral theory alternative to utilitarianism and that addresses the problem of distributive justice . The theory uses an updated form of Kantian philosophy and a variant form of conventional social contract theory. Rawls's theory of justice is fully a political theory of justice as opposed to other forms of justice discussed in other disciplines and contexts.

"Justice as Fairness: Political not Metaphysical" is an essay by John Rawls, published in 1985. In it he describes his conception of justice. It comprises two main principles of liberty and equality; the second is subdivided into fair equality of opportunity and the difference principle.

Public reason requires that the moral or political rules that regulate our common life be, in some sense, justifiable or acceptable to all those persons over whom the rules purport to have authority. It is an idea with roots in the work of Thomas Hobbes, Immanuel Kant, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and has become increasingly influential in contemporary moral and political philosophy as a result of its development in the work of John Rawls, Jürgen Habermas, and Gerald Gaus, among others.

Michael Joseph Sandel is an American political philosopher and the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Government at Harvard University, where his course Justice was the university's first course to be made freely available online and on television. It has been viewed by tens of millions of people around the world, including in China, where Sandel was named the 2011's "most influential foreign figure of the year".

Michael Laban Walzer is an American political theorist and public intellectual. A professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey, he is editor emeritus of the left-wing magazine Dissent, which he has been affiliated with since his years as an undergraduate at Brandeis University, an advisory editor of the Jewish journal Fathom, and sits on the editorial board of the Jewish Review of Books.

Thomas Winfried Menko Pogge is a German philosopher and is the Director of the Global Justice Program and Leitner Professor of Philosophy and International Affairs at Yale University, United States. In addition to his Yale appointment, he is the Research Director of the Centre for the Study of the Mind in Nature at the University of Oslo, Norway, a Professorial Research Fellow at the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics at Charles Sturt University, Australia, and Professor of Political Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire's Centre for Professional Ethics, England. Pogge is also an editor for social and political philosophy for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and a member of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters.

Political Liberalism is a 1993 book by the American philosopher John Rawls, an update to his earlier A Theory of Justice (1971). In it, he attempts to show that his theory of justice is not a "comprehensive conception of the good" but is instead compatible with a liberal conception of the role of justice, namely, that government should be neutral between competing conceptions of the good. Rawls tries to show that his two principles of justice, properly understood, form a "theory of the right" which would be supported by all reasonable individuals, even under conditions of reasonable pluralism. The mechanism by which he demonstrates this is called "overlapping consensus". Here he also develops his idea of public reason.

Desert in philosophy is the condition of being deserving of something, whether good or bad. It is sometimes called moral desert to clarify the intended usage and distinguish it from the dry desert biome. It is a concept often associated with justice and morality: that good deeds should be rewarded and evil deeds punished.

Robert B. Talisse is an American philosopher and political theorist. He is currently Professor of Philosophy and former Chair of the Philosophy Department at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, where he is also a Professor of Political Science. Talisse is a former editor of the academic journal Public Affairs Quarterly, and a regular contributor to the blog 3 Quarks Daily, where he posts a monthly column with his frequent co-author and fellow Vanderbilt philosopher Scott Aikin. He earned his PhD in Philosophy from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York in 2001. His principal area of research is political philosophy, with an emphasis on democratic theory and liberalism.

Justice: What's the Right Thing to Do? is a 2009 book on political philosophy by Michael J. Sandel.

An Introduction to Animals and Political Theory is a 2010 textbook by the British political theorist Alasdair Cochrane. It is the first book in the publisher Palgrave Macmillan's Animal Ethics Series, edited by Andrew Linzey and Priscilla Cohn. Cochrane's book examines five schools of political theory—utilitarianism, liberalism, communitarianism, Marxism and feminism—and their respective relationships with questions concerning animal rights and the political status of (non-human) animals. Cochrane concludes that each tradition has something to offer to these issues, but ultimately presents his own account of interest-based animal rights as preferable to any. His account, though drawing from all examined traditions, builds primarily upon liberalism and utilitarianism.

Alasdair Cochrane is a British political theorist and ethicist who is currently Professor of Political Theory in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Sheffield. He is known for his work on animal rights from the perspective of political theory, which is the subject of his two books: An Introduction to Animals and Political Theory and Animal Rights Without Liberation. His third book, Sentientist Politics, was published by Oxford University Press in 2018. He is a founding member of the Centre for Animals and Social Justice, a UK-based think tank focused on furthering the social and political status of nonhuman animals. He joined the Department at Sheffield in 2012, having previously been a faculty member at the Centre for the Study of Human Rights, London School of Economics. Cochrane is a sentientist. Sentientism is a naturalistic worldview that grants moral consideration to all sentient beings.

Free Market Fairness is a 2012 book of political philosophy written by John Tomasi, president of the Heterodox Academy and former Professor of Political Philosophy at Brown University. Tomasi presents the concept of "free market fairness" or "market democracy," a middle ground between Friedrich Hayek and John Rawls's ideas. The book was widely reviewed.