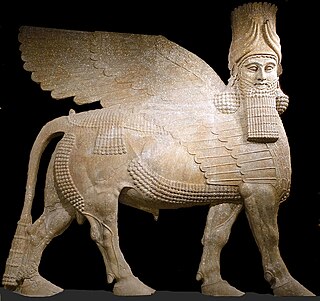

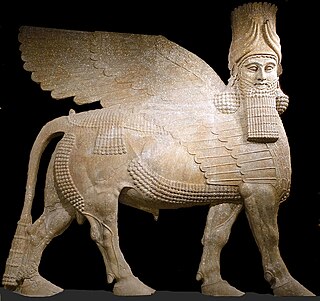

Assyria was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC, then to a territorial state, and eventually an empire from the 14th century BC to the 7th century BC.

Bahram II was the fifth Sasanian King of Kings (shahanshah) of Iran, from 274 to 293. He was the son and successor of Bahram I. Bahram II, while still in his teens, ascended the throne with the aid of the powerful Zoroastrian priest Kartir, just like his father had done.

Shapur I was the second Sasanian King of Kings of Iran. The dating of his reign is disputed, but it is generally agreed that he ruled from 240 to 270, with his father Ardashir I as co-regent until the death of the latter in 242. During his co-regency, he helped his father with the conquest and destruction of the Arab city of Hatra, whose fall was facilitated, according to Islamic tradition, by the actions of his future wife al-Nadirah. Shapur also consolidated and expanded the empire of Ardashir I, waged war against the Roman Empire, and seized its cities of Nisibis and Carrhae while he was advancing as far as Roman Syria. Although he was defeated at the Battle of Resaena in 243 by Roman emperor Gordian III, he was the following year able to win the Battle of Misiche and force the new Roman Emperor Philip the Arab to sign a favorable peace treaty that was regarded by the Romans as "a most shameful treaty".

Ardashir II, was the Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 379 to 383. He was the brother of his predecessor, Shapur II, under whom he had served as vassal king of Adiabene, where he fought alongside his brother against the Romans. Ardashir II was appointed as his brother's successor to rule interimly till the latter's son Shapur III reached adulthood. Ardashir II's short reign was largely uneventful, with the Sasanians unsuccessfully trying to maintain rule over Armenia.

Narseh was the seventh Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 293 to 303.

Adiabene was an ancient kingdom in northern Mesopotamia, corresponding to the northwestern part of ancient Assyria. The size of the kingdom varied over time; initially encompassing an area between the Zab Rivers, it eventually gained control of Nineveh, and starting at least with the rule of Monobazos I, Gordyene became an Adiabenian dependency. It reached its zenith under Izates II, who was granted the district of Nisibis by the Parthian king Artabanus II as a reward for helping him regain his throne. Adiabene's eastern borders stopped at the Zagros Mountains, adjacent to the region of Media. Arbela served as the capital of Adiabene.

Vologases I was the King of Kings of the Parthian Empire from 51 to 78. He was the son and successor of Vonones II. He was succeeded by his younger son Pacorus II, who continued his policies.

Phraates III, was King of Kings of the Parthian Empire from 69 BC to 57 BC. He was the son and successor of Sinatruces.

The Roman–Persian Wars, also known as the Roman–Iranian Wars, were a series of conflicts between states of the Greco-Roman world and two successive Iranian empires: the Parthian and the Sasanian. Battles between the Parthian Empire and the Roman Republic began in 54 BC; wars began under the late Republic, and continued through the Roman and Sasanian empires. A plethora of vassal kingdoms and allied nomadic nations in the form of buffer states and proxies also played a role. The wars were ended by the early Muslim conquests, which led to the fall of the Sasanian Empire and huge territorial losses for the Byzantine Empire, shortly after the end of the last war between them.

Assyria was a short-lived Roman province in Mesopotamia that was created by Trajan in 116 during his campaign against the Parthian Empire. After Trajan's death, the newly proclaimed emperor Hadrian ordered the evacuation of Assyria in 118.

Corduene was an ancient historical region, located south of Lake Van, present-day eastern Turkey.

Abdissares was the first king of Adiabene, ruling sometime in the first half of the 2nd-century BC. Scholarship initially considered him to be the ruler of Sophene, due to stylistic similarities between his coins and the ones in Commagene and Sophene. However, this has now been debunked. It has now been established that Abdissares' name—contrary to the Sophenian kings—was not of Iranian origin, but of Semitic, meaning "servant of Ishtar," a name primarily used by Semitic inhabitants. The goddess Ishtar enjoyed great popularity in the heartland of ancient Assyria, where Adiabene was located.

The SasanianEmpire, officially known as Eranshahr was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th–8th centuries AD. Named after the House of Sasan, it endured for over four centuries, from 224 to 651 AD, making it the longest-lived Persian imperial dynasty. The Sasanian Empire succeeded the Parthian Empire, and re-established the Persians as a major power in late antiquity alongside its neighbouring arch-rival, the Roman Empire.

The Battle of Misiche, Mesiche (Μεσιχή), or Massice was fought between the Sasanians and the Romans in Misiche, Mesopotamia.

The history of the Assyrians encompasses nearly five millennia, covering the history of the ancient Mesopotamian civilization of Assyria, including its territory, culture and people, as well as the later history of the Assyrian people after the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 609 BC. For purposes of historiography, ancient Assyrian history is often divided by modern researchers, based on political events and gradual changes in language, into the Early Assyrian, Old Assyrian, Middle Assyrian, Neo-Assyrian and post-imperial periods.

The Kingdom of Hatra was a 2nd-century Arab kingdom located between the Roman Empire and the Parthian Empire, mostly under Parthian suzerainty, located in modern-day northern Iraq.

Romans in Persia is related to the brief invasion and occupation of western and central areas of Parthia by the Romans during their empire. Emperor Trajan was even temporarily able to nominate a king of western parts of Parthia, Parthamaspates, as ruler of a Roman "client state" in Parthia.

Turan was a province of the Sasanian Empire located in present-day Pakistan. The province was mainly populated by Indians, and bordered Paradan in the west, Hind in the east, Sakastan in the north, and Makuran in the south. The main city and bastion of the province was Bauterna (Khuzdar/Quzdar).

Michał Marciak is Associate Professor of History at Jagiellonian University since 2018, specializing in Jewish studies. He has a MA in history (2007), a MA in theology (2007), and received his PhD in 2012 from the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Leiden.

The post-imperial period was the final stage of ancient Assyrian history, covering the history of the Assyrian heartland from the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 609 BC to the final sack and destruction of Assur, Assyria's ancient religious capital, by the Sasanian Empire c. AD 240. There was no independent Assyrian state during this time, with Assur and other Assyrian cities instead falling under the control of the successive Median, Neo-Babylonian, Achaemenid, Seleucid and Parthian empires. The period was marked by the continuance of ancient Assyrian culture, traditions and religion, despite the lack of an Assyrian kingdom. The ancient Assyrian dialect of the Akkadian language went extinct however, completely replaced by Aramaic by the 5th century BC.