Space exploration is the use of astronomy and space technology to explore outer space. While the exploration of space is currently carried out mainly by astronomers with telescopes, its physical exploration is conducted both by uncrewed robotic space probes and human spaceflight. Space exploration, like its classical form astronomy, is one of the main sources for space science.

Mariner 1, built to conduct the first American planetary flyby of Venus, was the first spacecraft of NASA's interplanetary Mariner program. Developed by Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and originally planned to be a purpose-built probe launched summer 1962, Mariner 1's design was changed when the Centaur proved unavailable at that early date. Mariner 1, were then adapted from the lighter Ranger lunar spacecraft. Mariner 1 carried a suite of experiments to determine the temperature of Venus as well to measure magnetic fields and charged particles near the planet and in interplanetary space.

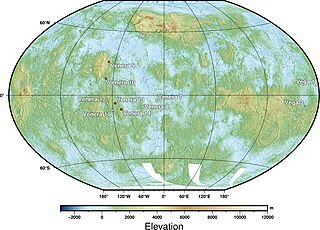

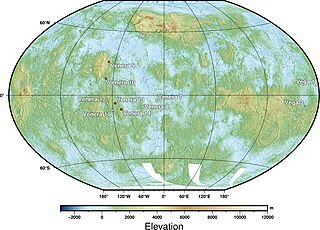

The Venera program was a series of space probes developed by the Soviet Union between 1961 and 1984 to gather information about the planet Venus.

This is a timeline of Solar System exploration ordering events in the exploration of the Solar System by date of spacecraft launch. It includes:

Pioneer 3 was a spin-stabilized spacecraft launched at 05:45:12 GMT on 6 December 1958 by the U.S. Army Ballistic Missile Agency in conjunction with NASA, using a Juno II rocket. This spacecraft was intended as a lunar probe, but failed to go past the Moon and into a heliocentric orbit as planned. It did however reach an altitude of 102,360 km before falling back to Earth. The revised spacecraft objectives were to measure radiation in the outer Van Allen radiation belt using two Geiger-Müller tubes and to test the trigger mechanism for a lunar photographic experiment.

Tyazhely Sputnik, also known by its development name as Venera 1VA No. 1, and in the West as Sputnik 7, was a Soviet spacecraft, which was intended to be the first spacecraft to explore Venus. Due to a problem with its upper stage it failed to leave low Earth orbit. In order to avoid acknowledging the failure, the Soviet government instead announced that the entire spacecraft, including the upper stage, was a test of a "Heavy Satellite" which would serve as a launch platform for future missions. This resulted in the upper stage being considered a separate spacecraft, from which the probe was "launched", on several subsequent missions.

Venera 1, also known as Venera-1VA No.2 and occasionally in the West as Sputnik 8 was the first spacecraft to perform an interplanetary flight and the first to fly past Venus, as part of the Soviet Union's Venera programme. Launched in February 1961, it flew past Venus on 19 May of the same year; however, radio contact with the probe was lost before the flyby, resulting in it returning no data.

Kosmos 27, also known as Zond 3MV-1 No.3 was a space mission intended as a Venus impact probe. The spacecraft was launched by a Molniya 8K78 carrier rocket from Baikonur. The Blok L stage and probe reached Earth orbit successfully, but the attitude control system failed to operate.

S.P. Korolev Rocket and Space Corporation "Energia" is a Russian manufacturer of spacecraft and space station components. Its name is derived from the Russian word for energy and is also named for Sergei Pavlovich Korolev, the first chief of its design bureau and the driving force behind early Soviet accomplishments in space exploration.

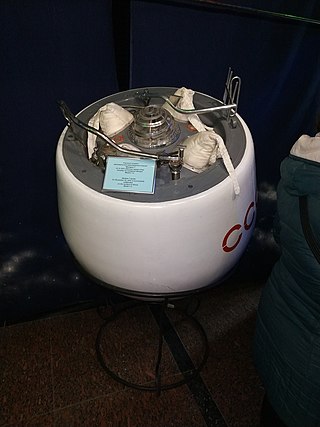

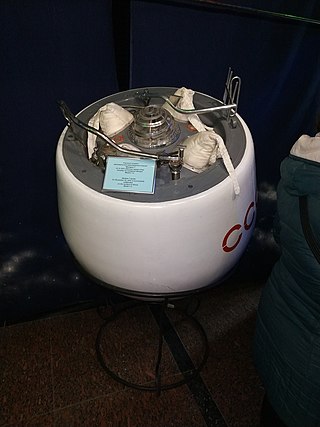

A lander is a spacecraft that descends towards, then comes to rest on the surface of an astronomical body other than Earth. In contrast to an impact probe, which makes a hard landing that damages or destroys the probe upon reaching the surface, a lander makes a soft landing after which the probe remains functional.

Venera 3 was a Venera program space probe that was built and launched by the Soviet Union to explore the surface of Venus. It was launched on 16 November 1965 at 04:19 UTC from Baikonur, Kazakhstan, USSR. The probe comprised an entry probe, designed to enter the Venus atmosphere and parachute to the surface, and a carrier/flyby spacecraft, which carried the entry probe to Venus and also served as a communications relay for the entry probe.

Venera 7 was a Soviet spacecraft, part of the Venera series of probes to Venus. When it landed the Venusian surface on 15 December 1970, it became the first spacecraft to soft land on another planet and the first to transmit data from there back to Earth.

Venera 4, also designated 4V-1 No.310, was a probe in the Soviet Venera program for the exploration of Venus. The probe comprised a lander, designed to enter the Venusian atmosphere and parachute to the surface, and a carrier/flyby spacecraft, which carried the lander to Venus and served as a communications relay for it.

Venera 13 was part of the Soviet Venera program meant to explore Venus.

A Moon landing or lunar landing is the arrival of a spacecraft on the surface of the Moon, including both crewed and robotic missions. The first human-made object to touch the Moon was Luna 2 in 1959.

A lunar lander or Moon lander is a spacecraft designed to land on the surface of the Moon. As of 2024, the Apollo Lunar Module is the only lunar lander to have ever been used in human spaceflight, completing six lunar landings from 1969 to 1972 during the United States' Apollo Program. Several robotic landers have reached the surface, and some have returned samples to Earth.

Spaceflight began in the 20th century following theoretical and practical breakthroughs by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, Robert H. Goddard, and Hermann Oberth, each of whom published works proposing rockets as the means for spaceflight. The first successful large-scale rocket programs were initiated in Nazi Germany by Wernher von Braun. The Soviet Union took the lead in the post-war Space Race, launching the first satellite, the first animal, the first human and the first woman into orbit. The United States landed the first men on the Moon in 1969. Through the late 20th century, France, the United Kingdom, Japan, and China were also working on projects to reach space.

A planetary flyby is the act of sending a space probe past a planet or a dwarf planet close enough to record scientific data. This is a subset of the overall concept of a flyby in spaceflight.