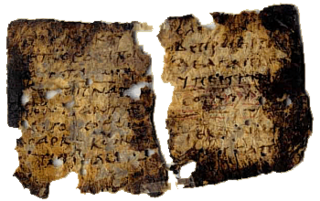

The Apostolic Constitutions

The Apostolic Constitutions consist of eight books purporting to have been written by St. Clement of Rome (died c. 104). The first six books are an interpolated edition of the Didascalia Apostolorum ("Teaching of the Apostles and Disciples", written in the first half of the third century and since edited in a Syriac version by de Lagarde, 1854); the seventh book is an equally modified version of the Didache (Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, probably written in the first century, and found by Philotheos Bryennios in 1883) with a collection of prayers. The eighth book contains a complete liturgy and the eighty-five "Apostolic Canons". There is also part of a liturgy modified from the Didascalia in the second book.

It has been suggested that the compiler of the Apostolic Constitutions may be the same person as the author of the six spurious letters of St. Ignatius (Pseudo-Ignatius). In any case he was a Syrian Christian, probably an Apollinarist, living in or near Antioch either at the end of the fourth or the beginning of the fifth century. And the liturgy that he describes in his eighth book is that used in his time by the Church of Antioch, with certain modifications of his own. That the writer was an Antiochene Syrian and that he describes the liturgical use of his own country is shown by various details, such as the precedence given to Antioch (VII, xlvi, VIII, x, etc.); his mention of Christmas (VIII, xxxiii), which was kept at Antioch since about 375, nowhere else in the East till about 430 (Louis Duchesne, Origines du culte chrétien, 248); the fact that Holy Week and Lent together make up seven weeks (V, xiii) as at Antioch, whereas in Palestine and Egypt, as throughout the West, Holy Week was the sixth week of Lent; that the chief source of his "Apostolic Canons" is the Synod of Antioch in encœniis (341); and especially by the fact that his liturgy is obviously built up on the same lines as all the Syrian ones. There are, however, modifications of his own in the prayers, Creed, and Gloria, where the style and the idioms are obviously those of the interpolator of the Didascalia (see the examples in Brightman, "Liturgies", I, xxxiii-xxxiv), and are often very like those of Pseudo-Ignatius also (ib., xxxv). The rubrics are added by the compiler, apparently from his own observations.

The Liturgy of the eighth book

The liturgy of the eighth book of the Apostolic Constitutions, then, represents the use of Antioch in the fourth century. Its order is this:

First comes the Mass of the Catechumens. After the readings (of the Law, the Prophets, the Epistles, Acts, and Gospels) the bishop greets the people with II Cor., xiii, 13 (The grace of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the charity of God and the communication of the Holy Ghost be with you all).

They answer: "And with thy spirit"; and he "speaks to the people words of comfort." There then follows a litany for the catechumens, to each invocation of which the people answer " Kyrie eleison "; the bishop says a collect (short general prayer) and the deacon dismisses the catechumens. Similar litanies and collects follow for the Energumens, the Illuminandi (photizómenoi, people about to be baptized) and the public penitents, and each time they are dismissed after the collect for them.

The Mass of the Faithful begins with a longer litany for various causes, for peace, the Church, bishops (James, Clement, Evodius, and Annianus are named), priests, deacons, servers, readers, singers, virgins, widows, orphans, married people, the newly baptized, prisoners, enemies, persecutors etc., and finally "for every Christian soul".

After the litany follows its collect, then another greeting from the bishop and the kiss of peace. Before the Offertory the deacons stand at the men's doors and the subdeacons at those of the women "that no one may go out, nor the door be opened", and the deacon again warns all catechumens, infidels, and heretics to retire, the mothers to look after their children, no one to stay in hypocrisy, and all to stand in fear and trembling.

The deacons bring the offerings to the bishop at the altar. The priests stand around, two deacons wave fans (‘ripídia) over the bread and wine and the Anaphora (canon) begins. The bishop again greets the people with the sursum corda , the words of II Cor., xiii, 13, along with its versicle as it appears in most other forms of the Divine Liturgy, followed by the Eucharistic Preface the Eucharistic prayer begins.

He speaks of the "only begotten Son, the Word and God, Saving Wisdom, first born of all creatures, Angel of thy great counsel", refers at some length to the garden of Eden, Abel, Henoch, Abraham, Melchisedech, Job, and other saints of the Old Law. When he has said the words: "the numberless army of Angels … the Cherubim and six-winged Seraphim … together with thousands of thousand Archangels and myriad myriads of Angels unceasingly and without silence cry out", "all the people together say: 'Holy, holy, holy the Lord of Hosts, the heaven and earth are full of His glory, blessed forever, Amen.'"

The bishop then again takes up the word and continues: "Thou art truly holy and all-holy, highest and most exalted for ever. And thine only-begotten Son, our Lord and God Jesus Christ, is holy …"; and so he comes to the words of Institution: "in the night in which He was betrayed, taking bread in His holy and blameless hands and looking up to Thee, His God and Father, and breaking He gave to His disciples saying: This is the Mystery of the New Testament; take of it, eat. This is My body, broken for many for the remission of sins. So also having mixed the cup of wine and water, and having blessed it, He gave to them saying: Drink you all of this. This is My blood shed for many for the remission of sins. Do this in memory of Me. For as often as you eat this bread and drink this cup, you announce My death until I come."

Then follows the Anamnesis ("Remembering therefore His suffering and death and resurrection and return to heaven and His future second coming …"), the Epiclesis or invocation ("sending Thy Holy Spirit, the witness of the sufferings of the Lord Jesus to this sacrifice, that He may change this bread to the body of thy Christ and this cup to the blood of thy Christ …"), and a sort of litany (the great Intercession) for the Church, clergy, the Emperor, and for all sorts and conditions of men, which ends with a doxology, "and all the people say: Amen."

In this litany is a curious petition (after that for the Emperor and the army) which joins the saints to living people for whom the bishop prays: "We also offer to thee for (‘upér) all thy holy and eternally well-pleasing patriarchs, prophets, just apostles, martyrs, confessors, bishops, priests, deacons, subdeacons, readers, singers, virgins, widows, laymen, and all those whose names thou knowest."

After the Kiss of Peace (The peace of God be with you all) the deacon calls upon the people to pray for various causes which are nearly the same as those of the bishop's litany and the bishop gathers up their prayers in a collect. He then shows them the Holy Eucharist, saying: "Holy things for the holy" and they answer: "One is holy, one is Lord, Jesus Christ in the glory of God the Father, etc." The bishop gives the people Holy Communion in the form of bread, saying to each: "The body of Christ", and the communicant answers "Amen". The deacon follows with the chalice, saying: "The blood of Christ, chalice of life." R. "Amen." While they receive, the xxxiii Psalm (I will bless the Lord at all times) is said. After Communion the deacons take what is left of the Blessed Sacrament to the vestry (pastophória). There follows a short thanksgiving, the bishop dismisses the people and the deacon ends by saying: "Go in peace."

Throughout this liturgy the compiler supposes that it was drawn up by the Apostles and he inserts sentences telling us which Apostle composed each separate part, for instance: "And I, James, brother of John the son of Zebedee, say that the deacon shall say at once: 'No one of the catechumens,'" etc. The second book of the Apostolic Constitutions contains the outline of a liturgy (hardly more than the rubrics) which practically coincides with this one.