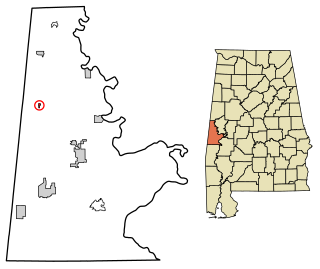

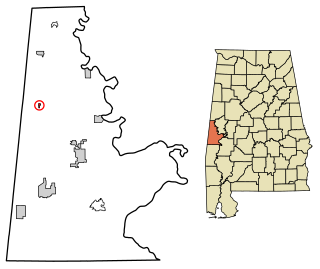

Emelle is a town in Sumter County, Alabama, United States. It was named after the daughters of the man who donated the land for the town. The town was started in the 19th century but not incorporated until 1981. The daughters of the man who donated were named Emma Dial and Ella Dial, so he combined the two names to create Emelle. Emelle was famous for its great cotton. The first mayor of Emelle was James Dailey. He served two terms. The current mayor is Roy Willingham Sr. The population was 32 at the 2020 census.

Brownfield is previously-developed land that has been abandoned or underutilized, and which may carry pollution, or a risk of pollution, from industrial use. The specific definition of brownfield land varies and is decided by policy makers and land developers within different countries. The main difference in definitions of whether a piece of land is considered a brownfield or not depends on the presence or absence of pollution. Overall, brownfield land is a site previously developed for industrial or commercial purposes and thus requires further development before reuse.

Toxic waste is any unwanted material in all forms that can cause harm. Mostly generated by industry, consumer products like televisions, computers, and phones contain toxic chemicals that can pollute the air and contaminate soil and water. Disposing of such waste is a major public health issue.

Superfund is a United States federal environmental remediation program established by the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA). The program is administered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and is designed to pay for investigating and cleaning up sites contaminated with hazardous substances. Sites managed under this program are referred to as Superfund sites. Of the tens of thousands of sites selected for possible action under the Superfund program, 1178 remain on the National Priorities List (NPL) that makes them eligible for cleanup under the Superfund program. Sites on the NPL are considered the most highly contaminated and undergo longer-term remedial investigation and remedial action (cleanups). The state of New Jersey, the fifth smallest state in the U.S., is the location of about ten percent of the priority Superfund sites, a disproportionate amount.

New Jersey Meadowlands, also known as the Hackensack Meadowlands after the primary river flowing through it, is a general name for a large ecosystem of wetlands in northeastern New Jersey in the United States, a few miles to the west of New York City. During the 20th century, much of the Meadowlands area was urbanized, and it became known for being the site of large landfills and decades of environmental abuse. A variety of projects began in the late 20th century to restore and conserve the remaining ecological resources in the Meadowlands.

Environmental racism, ecological racism, or ecological apartheid is a form of racism leading to negative environmental outcomes such as landfills, incinerators, and hazardous waste disposal disproportionately impacting communities of color, violating substantive equality. Internationally, it is also associated with extractivism, which places the environmental burdens of mining, oil extraction, and industrial agriculture upon indigenous peoples and poorer nations largely inhabited by people of color.

Munisport Landfill is a closed landfill located in North Miami, Florida adjacent to a low-income community, a regional campus of Florida International University, Oleta River State Park, and estuarine Biscayne Bay.

Warren County PCB Landfill was a PCB landfill located in Warren County, North Carolina, near the community of Afton south of Warrenton. The landfill was created in 1982 by the State of North Carolina as a place to dump contaminated soil as result of an illegal PCB dumping incident. The site, which is about 150 acres (0.61 km2), was extremely controversial and led to years of lawsuits. Warren County was one of the first cases of environmental justice in the United States and set a legal precedent for other environmental justice cases. The site was approximately three miles south of Warrenton. The State of North Carolina owned about 19 acres (77,000 m2) of the tract where the landfill was located, and Warren County owned the surrounding acreage around the borders.

The Kin-Buc Landfill is a 220-acre (0.89 km2) Superfund site located in Edison, New Jersey where 70 million US gallons (260,000 m3) of liquid toxic waste and 1 million tons of solid waste were dumped. It was active from the late 1940s to 1976. It was ordered closed in 1977. Cleanup operations have been underway to address environmental issues with contamination from 1980s through to 2000s. This site was one of the largest superfund sites in New Jersey having taken in around 90 million US gallons (340,000 m3). The site is heavily contaminated with PCBs, which leaked into Edmonds Creek, a tributary of the Raritan River.

The former Operating Industries Inc. Landfill is a Superfund site located in Monterey Park, California at 900 N Potrero Grande Drive. From 1948 to 1984, the landfill accepted 30 million tons of solid municipal waste and 300 million US gallons (1,100,000 m3) of liquid chemicals. Accumulating over time, the chemical waste polluted the air, leached into groundwater, and posed a fire hazard, spurring severely critical public health complaints. Recognizing OII Landfill's heavy pollution, EPA placed the financial responsibility of the dump's clean-up on the main waste-contributing companies, winning hundreds of millions of dollars in settlements for the protection of human health and the environment.

Brownfields are defined by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as properties that are complicated by the potential presence of pollutants or otherwise hazardous substances. The pollutants such as heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB), poly- and per-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) contaminating these sites are typically due to commercial or industrial work that was previously done on the land. This includes locations such as abandoned gas stations, laundromats, factories, and mills. By a process called land revitalization, these once polluted sites can be remediated into locations that can be utilized by the public.

The Ringwood Mines landfill site is a 500 acres (200 ha) former iron mining site located in the borough of Ringwood, New Jersey. From 1967 to 1980, the Ford Motor Company dumped hazardous waste on this land, which negatively affected the health and properties of Ramapough Mountain Indians. This led to Mann V. Ford, a 1997 lawsuit between Ramapough Lenape Tribe's lawsuit of the Ford Motor Company.

Shpack Landfill is a hazardous waste site in Norton, Massachusetts. After assessment by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) it was added to the National Priorities List in October 1986 for long-term remedial action. The site cleanup is directed by the federal Superfund program. The Superfund site covers 9.4 acres, mostly within Norton, with 3.4 acres in the adjoining city of Attleboro. The Norton site was operated as a landfill dump accepting domestic and industrial wastes, including low-level radioactive waste, between 1946 and 1965. The source of most of the radioactive waste, consisting of uranium and radium, was Metals and Controls Inc. which made enriched uranium fuel elements for the U.S. Navy under contract with the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. Metals and Controls merged with Texas Instruments in 1959. The Shpack landfill operation was shut down by a court order in 1965.

Moyer's Landfill was a privately owned landfill in Collegeville, Pennsylvania, United States. It was originally farmland outside the town. In the 1940s, the owner started accepting trash and municipal waste as a way to make additional money. The original landfill was 39 acres and did not have a liner to protect the land from contaminate. A liner was added to a new section in the late 1970s. Over time, the landfill accepted sewage, and industrial wastes which contained hazardous substances in addition to municipal waste. The site was closed by the EPA in 1981, and was one of the first "Superfund" sites added to the National Priorities List.

Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice, formed in 1997, is a multiracial grassroots organization based in San Francisco that works with low-income and working class urban, rural, and indigenous communities. It runs campaigns in the United States to build grassroots networks, and advocate for social justice.

Environmental, ecological or green gentrification is a process in which cleaning up pollution or providing green amenities increases local property values and attracts wealthier residents to a previously polluted or disenfranchised neighbourhood. Green amenities include green spaces, parks, green roofs, gardens and green and energy efficient building materials. These initiatives can heal many environmental ills from industrialization and beautify urban landscapes. Additionally, greening is imperative for reaching a sustainable future. However, if accompanied by gentrification, these initiatives can have an ambiguous social impact. More specifically, in certain cases the introduction of green amenities might lead to (1) the physical displacement of low income households due to soaring housing costs, and/or (2) the cultural, social, and political displacement of long-time residents. First coined by Sieg et al. (2004), environmental gentrification is a relatively new concept, although it can be considered as a new hybrid of the older and wider topics of gentrification and environmental justice. Social implications of greening projects specifically with regards to housing affordability and displacement of vulnerable citizens. Greening in cities can be both healthy and just.

Guam v. United States, 593 U.S. ___ (2021), was a U.S. Supreme Court case dealing with a dispute on fiscal responsibility for environmental and hazardous cleanup of the Ordot Dump created by the United States Navy on the island of Guam in the 1940s, which Guam then ran after becoming a territory in 1950 until the landfill's closure in 2011. The Supreme Court ruled unanimously that under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, Guam had filed its lawsuit to recover a portion of cleanup costs for the landfill from the United States government in a timely manner, allowing their case to proceed.

Ordot Dump, also known as Ordot Landfill, was a landfill on the western Pacific island of Guam that operated from the 1940s until 2011. Originally operated by the U.S. military, ownership was transferred to the Government of Guam in 1950, though it continued to receive all waste on the island, including from Naval Base Guam and Andersen Air Force Base, through the 1970s.

Camden, New Jersey has faced environmental issues due to its history of heavy industry and the improper disposal of contaminants. Environmental concerns include air/water pollution and soil contamination, as well as Superfund sites throughout the city. In recent years, illegal dumping has become a issue due to all the vacant lots throughout the city and lack of security and maintenance coming from City Hall.