Cernunnos is a Celtic stag god. His name is only clearly attested once, on the 1st-century Pillar of the Boatmen from Paris, where it is associated with an image of an aged, antlered figure with torcs around his horns.

Mercury is a major god in Roman religion and mythology, being one of the 12 Dii Consentes within the ancient Roman pantheon. He is the god of financial gain, commerce, eloquence, messages, communication, travelers, boundaries, luck, trickery, and thieves; he also serves as the guide of souls to the underworld and the "messenger of the gods".

In Gallo-Roman religion, Rosmerta was a goddess of fertility and abundance, her attributes being those of plenty such as the cornucopia. Rosmerta is attested by statues and by inscriptions. In Gaul she was often depicted with the Roman god Mercury as her consort, but is sometimes found independently.

Lleu Llaw Gyffes (Welsh pronunciation:[ˈɬɛɨˈɬauˈɡəfɛs], sometimes incorrectly spelled as Llew Llaw Gyffes, is a hero of Welsh mythology. He appears most prominently in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi, the tale of Math fab Mathonwy, which tells the tale of his birth, his marriage, his death, his resurrection and his accession to the throne of Gwynedd. He is a warrior and magician, invariably associated with his uncle Gwydion.

Lugus is a Celtic god whose worship is attested in the epigraphic record. No depictions of the god are known. Lugus perhaps also appears in Roman sources and medieval Insular mythology.

The Horned Serpent appears in the mythologies of many cultures including Native American peoples, European, and Near Eastern mythology. Details vary among cultures, with many of the stories associating the mystical figure with water, rain, lightning, thunder, and rebirth. Horned Serpents were major components of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex of North American prehistory.

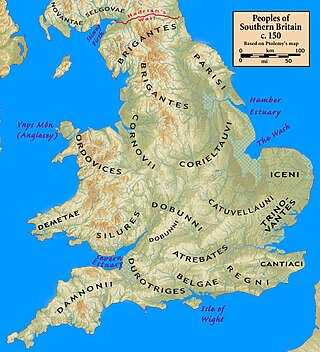

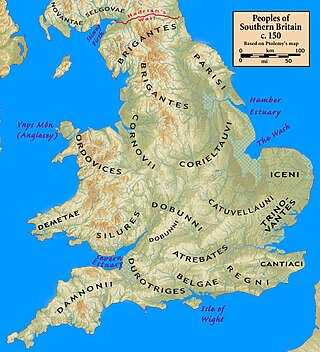

The Regni were a Celtic tribe or group of tribes living in Britain prior to the Roman Conquest, and later a civitas or canton of Roman Britain. They lived in what is now Sussex, as well as small parts of Hampshire, Surrey and Kent, with their tribal heartland at Noviomagus Reginorum.

Lugdunum was an important Roman city in Gaul, established on the current site of Lyon.

The Gundestrup cauldron is a richly decorated silver vessel, thought to date from between 200 BC and 300 AD, or more narrowly between 150 BC and 1 BC. This places it within the late La Tène period or early Roman Iron Age. The cauldron is the largest known example of European Iron Age silver work. It was found dismantled, with the other pieces stacked inside the base, in 1891, in a peat bog near the hamlet of Gundestrup in the Aars parish of Himmerland, Denmark. It is now usually on display in the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, with replicas at other museums; it was in the UK on a travelling exhibition called The Celts during 2015–2016.

The Pillar of the Boatmen is a monumental Roman column erected in Lutetia in honour of Jupiter by the guild of boatmen in the 1st century AD. It is the oldest monument in Paris and is one of the earliest pieces of representational Gallo-Roman art to carry a written inscription.

Ancient Celtic religion, commonly known as Celtic paganism, was the religion of the ancient Celtic peoples of Europe. Because there are no extant native records of their beliefs, evidence about their religion is gleaned from archaeology, Greco-Roman accounts, and literature from the early Christian period. Celtic paganism was one of a larger group of polytheistic Indo-European religions of Iron Age Europe.

Gallo-Roman religion is a fusion of the traditional religious practices of the Gauls, who were originally Celtic speakers, and the Roman and Hellenistic religions introduced to the region under Roman Imperial rule. It was the result of selective acculturation.

Atepomarus or Atepomaros in Celtic Gaul was a healing god from Mauvières (Indre). Apollo was associated with this god in the form Apollo Atepomarus.

Teutates is a Celtic god attested in literary and epigraphic sources. His name, derived from a proto-Celtic word meaning "tribe", suggests he was a tribal deity.

The gods and goddesses of the pre-Christian Celtic peoples are known from a variety of sources, including ancient places of worship, statues, engravings, cult objects, and place or personal names. The ancient Celts appear to have had a pantheon of deities comparable to others in Indo-European religion, each linked to aspects of life and the natural world. Epona was an exception and retained without association with any Roman deity. By a process of syncretism, after the Roman conquest of Celtic areas, most of these became associated with their Roman equivalents, and their worship continued until Christianization. Pre-Roman Celtic art produced few images of deities, and these are hard to identify, lacking inscriptions, but in the post-conquest period many more images were made, some with inscriptions naming the deity. Most of the specific information we have therefore comes from Latin writers and the archaeology of the post-conquest period. More tentatively, links can be made between ancient Celtic deities and figures in early medieval Irish and Welsh literature, although all these works were produced well after Christianization.

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, language, morals and way of life in a uniquely Gaulish context. The well-studied meld of cultures in Gaul gives historians a model against which to compare and contrast parallel developments of Romanization in other less-studied Roman provinces.

Celtic mythology is the body of myths belonging to the Celtic peoples. Like other Iron Age Europeans, Celtic peoples followed a polytheistic religion, having many gods and goddesses. The mythologies of continental Celtic peoples, such as the Gauls and Celtiberians, did not survive their conquest by the Roman Empire, the loss of their Celtic languages and their subsequent conversion to Christianity. Only remnants are found in Greco-Roman sources and archaeology. Most surviving Celtic mythology belongs to the Insular Celtic peoples. They preserved some of their myths in oral lore, which were eventually written down by Christian scribes in the Middle Ages. Irish mythology has the largest written body of myths, followed by Welsh mythology.

The God of Bouray is a Celtic bronze statuette dredged from the River Juine within Bouray-sur-Juine. The statuette is of a cross-legged human figure with an oversized head and hooved feet. It is thought to represent a Gallic god, perhaps the stag-god Cernunnos.

The God of Amiens is a Gallo-Roman bronze statuette found in Amiens, Somme. The statuette, which has been dated to the end of the 1st century CE, is of a male youth sat cross-legged, with the right ear of an animal, perhaps a deer's. This statuette is on display at the Musée de Picardie.

The God of Étang-sur-Arroux is a Gallo-Roman bronze statuette, probably found in the commune of Étang-sur-Arroux, not far from Autun, France.