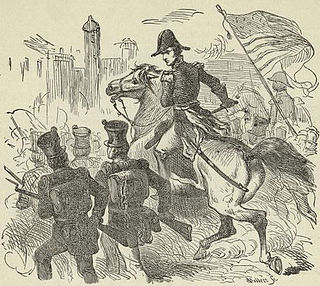

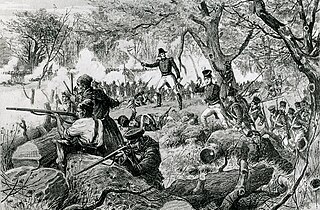

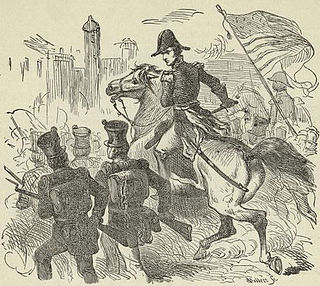

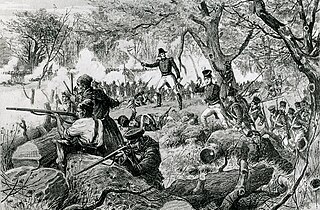

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815, between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the French Quarter of New Orleans, in the current suburb of Chalmette, Louisiana.

Jacques Philippe Villeré was the second Governor of Louisiana after it became a state. He was the first Creole and the first native of Louisiana to hold that office.

The Corps of Colonial Marines were two different British Marine units raised from former black slaves for service in the Americas, at the behest of Alexander Cochrane. The units were created at two separate periods: 1808-1810 during the Napoleonic Wars; and then again during the War of 1812; both units being disbanded once the military threat had passed. Apart from being created in each case by Cochrane, they had no connection with each other.

The Battle of Pensacola was a battle of the Creek War during the War of 1812, in which American forces fought against forces from the kingdoms of Britain and Spain who were aided by the Creek Indians and African-American slaves allied with the British. General Andrew Jackson led his infantry against British and Spanish forces controlling the city of Pensacola in Spanish Florida. Allied forces abandoned the city, and the remaining Spanish forces surrendered to Jackson.

James Pitot (1761–1831), also known as Jacques Pitot, was the third Mayor of New Orleans, after Cavelier Petit served for a ten-day interim following Mayor Boré's resignation. Because he had already attained American citizenship, he is sometimes called New Orleans' first American mayor.

Daniel Carmick was an officer in the United States Marine Corps.

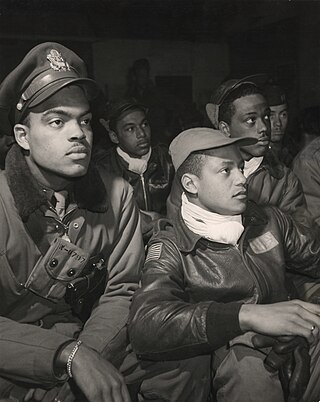

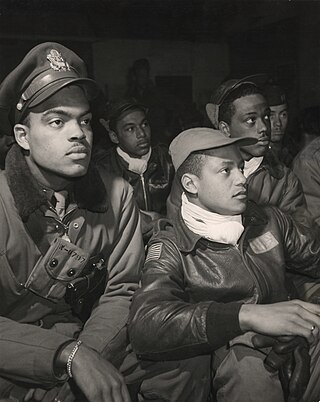

The military history of African Americans spans from the arrival of the first enslaved Africans during the colonial history of the United States to the present day. African Americans have participated in every war fought by or within the United States.

When the United States and the United Kingdom went to war against each other in 1812, the major land theatres of war were Upper Canada, Michigan Territory, Lower Canada and the Maritime Provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton . Each of the separate British administrations formed regular and fencible units, and both full-time and part-time militia units, many of which played a major part in the fighting over the two and a half years of the war.

The 1st Infantry Regiment is a regiment of the United States Army that draws its lineage from a line of post American Revolutionary War units and is credited with thirty-nine campaign streamers. The 1st Battalion, 1st Infantry is assigned as support to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York and to furnish the enlisted garrison for the academy and the Stewart Army Subpost. 2nd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment is an infantry component serving with the 2nd Stryker Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division at Joint Base Lewis–McChord, Washington.

Louisiana was a dominant population center in the southwest of the Confederate States of America, controlling the wealthy trade center of New Orleans, and contributing the French Creole and Cajun populations to the demographic composition of a predominantly Anglo-American country. In the antebellum period, Louisiana was a slave state, where enslaved African Americans had comprised the majority of the population during the eighteenth-century French and Spanish dominations. By the time the United States acquired the territory (1803) and Louisiana became a state (1812), the institution of slavery was entrenched. By 1860, 47% of the state's population were enslaved, though the state also had one of the largest free black populations in the United States. Much of the white population, particularly in the cities, supported slavery, while pockets of support for the U.S. and its government existed in the more rural areas.

Thomas Hinds was an American soldier and politician from the state of Mississippi, who served in the United States Congress from 1828 to 1831.

Jean Baptiste Plauché was a Louisiana soldier and politician. He was lieutenant governor of Louisiana from 1850 to 1853 under Governor Joseph M. Walker.

The 1st Louisiana Native Guard was a Confederate Louisianan militia that consisted of Creoles of color. Formed in 1861 in New Orleans, Louisiana, it was disbanded on April 25, 1862. Some of the unit's members joined the Union Army's 1st Louisiana Native Guard, which later became the 73rd Regiment Infantry of the United States Colored Troops.

Joshua Lewis was a judge of the Superior Court of the Territory of Orleans and, after Louisiana became a state, the 1st Judicial District Court of that state.

The 9th Louisiana Infantry Regiment or Louisiana Tigers was the common nickname for certain infantry troops from the state of Louisiana in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. Originally applied to a specific company, the nickname expanded to a battalion, then to a brigade, and eventually to all Louisiana troops within the Army of Northern Virginia. Although the exact composition of the Louisiana Tigers changed as the war progressed, they developed a reputation as fearless, hard-fighting shock troops.

The 1st Louisiana Native Guard was one of the first all-black regiments in the Union Army. Based in New Orleans, Louisiana, it played a prominent role in the Siege of Port Hudson. Its members included a minority of free men of color from New Orleans; most were African-American former slaves who had escaped to join the Union cause and gain freedom. A Confederate regiment by the same name served in the Louisiana militia made up entirely of free men of color.

Jordan Bankston Noble also known as Jordan B. Noble was an African American soldier and public figure who is best known for his role as a military drummer in the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812. Noble's drum played a crucial role in relaying his commander's orders during the surprise assault against the British forces on December 23, 1814, and the main British advance on January 8, 1815. Jordan Noble also served in the Seminole Wars, Mexican-American War under Zachary Taylor, and the American Civil War for the Union.

Alabama Creoles are a Louisiana French group native to the region around Mobile, Alabama. They are the descendants of colonial French and Spanish settlers who arrived in Mobile in the 18th century. They are sometimes known as Cajans or Cajuns although they are distinct from the Cajuns of southern Louisiana, and most do not trace their roots to the French settlers of Acadia.

Jean-Louis Dolliole was an African-American architect in New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, during the 19th century. He was a free man of color who also worked as a cabinetmaker, home builder, contractor, planter and leader of the African-American community of New Orleans in the time of the Antebellum South. Dolloile is noted for the architectural design of several residential projects which continue in use as homes into the 21st century. The designs were early versions of the creole cottage that became a common style of homes in New Orleans and elsewhere in the southern United States. Dolliole was a leader in the early development of the Faubourg Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans.

The Louisiana Guard Battery was an artillery unit recruited from volunteers in Louisiana that fought in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. Formed from an infantry company sent to fight in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War, it was converted to an artillery company in July 1861. The battery fought at Cedar Mountain, Second Bull Run, Antietam, and Fredericksburg in 1862, and at Chancellorsville, Second Winchester, and Gettysburg in 1863. Most of the soldiers and all of the battery's guns were captured at Rappahannock Station on 7 November 1863. The surviving gunners manned heavy artillery pieces in the defenses of Richmond, Virginia, and the battery's remnant surrendered at Appomattox.