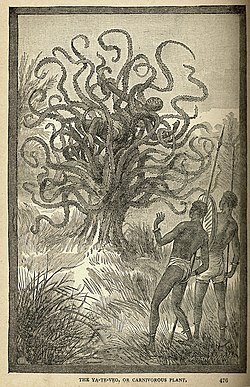

The Madagascar tree

The earliest known report of a man-eating plant originated as a literary fabrication written by journalist Edmund Spencer for the New York World . [2] Spencer's article first appeared in the daily edition of the New York World on 26 April 1874, and appeared again in the weekly edition of the newspaper two days later. [3] In the article, a letter was published by a purported German explorer named "Karl Leche" (also spelled as Karl or Carl Liche in later accounts), who provided a report of encountering a human sacrifice performed by the "Mkodo tribe" of Madagascar: [4] This story was picked up by many other newspapers of the day, which included the South Australian Register of 27 October 1874, [5] where it gained even greater notoriety. [6] Describing the tree, the account related:

The slender delicate palpi, with the fury of starved serpents, quivered a moment over her head, then as if instinct with demoniac intelligence fastened upon her in sudden coils round and round her neck and arms; then while her awful screams and yet more awful laughter rose wildly to be instantly strangled down again into a gurgling moan, the tendrils one after another, like great green serpents, with brutal energy and infernal rapidity, rose, retracted themselves, and wrapped her about in fold after fold, ever tightening with cruel swiftness and savage tenacity of anacondas fastening upon their prey. [7]

The hoax was given further publicity by Madagascar: Land of the Man-eating Tree, a book by Chase Osborn, who had been a Governor of Michigan. Osborn claimed that both the tribes and missionaries on Madagascar knew about the hideous tree, repeated the above Liche account, and acknowledged "I do not know whether this tigerish tree really exists or whether the bloodcurdling stories about it are pure myth. It is enough for my purpose if its story focuses your interest upon one of the least known spots of the world." [8]

In his 1955 book, Salamanders and other Wonders, science author Willy Ley determined that the Mkodo tribe, Carl Liche, and the Madagascar man-eating tree all appeared to be fabrications: "The facts are pretty clear by now. Of course the man eating tree does not exist. There is no such tribe." [9]

The vampire vine

William Thomas Stead, editor of Review of Reviews, published a brief article in October 1891 that discussed a story found in Lucifer magazine, describing a plant in Nicaragua called by the natives the devil's snare. This plant had the capability "to drain the blood of any living thing which comes within its death-dealing touch." According to the article:

Mr. Dunstan, naturalist, who has recently returned from Central America, where he spent nearly two years in the study of the flora and the fauna of the country, relates the finding of a singular growth in one of the swamps which surround the great lakes of Nicaragua. He was engaged in hunting for botanical and entomological specimens, when he heard his dog cry out, as if in agony, from a distance. Running to the spot whence the animal's cries came. Mr. Dunstan found him enveloped in a perfect network of what seemed to be a fine rope-like tissue of roots and fibers... The native servants who accompanied Mr. Dunstan manifested the greatest horror of the vine, which they call "the devil's snare", and were full of stories of its death-dealing powers. He was able to discover very little about the nature of the plant, owing to the difficulty of handling it, for its grasp can only be torn away with the loss of skin and even of flesh; but, as near as Mr. Dunstan could ascertain, its power of suction is contained in a number of infinitesimal mouths or little suckers, which, ordinarily closed, open for the reception of food. If the substance is animal, the blood is drawn off and the carcass or refuse then dropped. [12]

An investigation of Stead's review determined no such article was published in the October issue of Lucifer, and concluded that the story in Review of Reviews appeared to be a fabrication by the editor. [13] The story in fact appeared in the September issue, [14] preceded by a longer version in an 1889 newspaper describing Dunstan as a "well-known naturalist" from New Orleans. [15]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.