Edward "Ned" Maddrell was a Manx fisherman who, at the time of his death, was the last surviving native speaker of the Manx language.

Yn Chruinnaght is a cultural festival in the Isle of Man which celebrates Manx music, Manx language and culture, and links with other Celtic cultures.

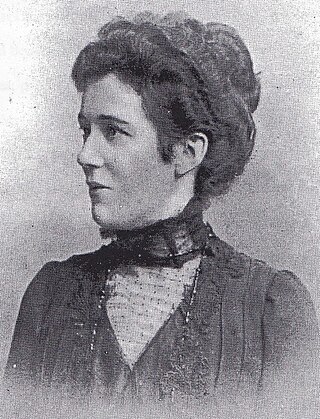

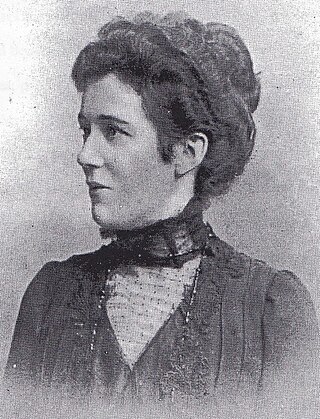

Sophia Morrison was a Manx cultural activist, folklore collector and author. Through her own work and role in encouraging and enthusing others, she is considered to be one of the key figures of the Manx cultural revival. She is best remembered today for writing Manx Fairy Tales, published in 1911, although her greatest influence was as an activist for the revitalisation of Manx culture, particularly through her work with the Manx Language Society and its journal, Mannin, which she edited from 1913 until her death.

Thomas Brian Stowell, also known as Brian Mac Stoyll, was a Manx radio personality, linguist, physicist, and author. He was formerly Yn Lhaihder to the Parliament of the Isle of Man, Tynwald. He is considered one of the primary people behind the revival of the Manx language.

Walter Clarke, or Walter y Chleree, was a Manx language speaker, activist, and teacher who was one of the last people to learn Manx from the few remaining native speakers on the Isle of Man. His work recording them with the Irish Folklore Commission helped to ensure that a spoken record of the Manx language survived.

John Joseph Kneen was a Manx linguist and scholar renowned for his seminal works on Manx grammar and on the place names and personal names of the Isle of Man. He is also a significant Manx dialect playwright and translator of Manx poetry. He is commonly best known for his translation of the Manx National Anthem into Manx.

Mona Douglas was a Manx cultural activist, folklorist, poet, novelist and journalist. She is recognised as the main driving force behind the modern revival of Manx culture and is acknowledged as the most influential Manx poet of the 20th century, but she is best known for her often controversial work to preserve and revive traditional Manx folk music and dance. She was involved in a great number of initiatives to revive interest and activity in Manx culture, including societies, classes, publications and youth groups. The most notable and successful of these was Yn Chruinnaght.

Josephine Kermode (1852–1937) was a Manx poet and playwright better known by the pen name "Cushag".

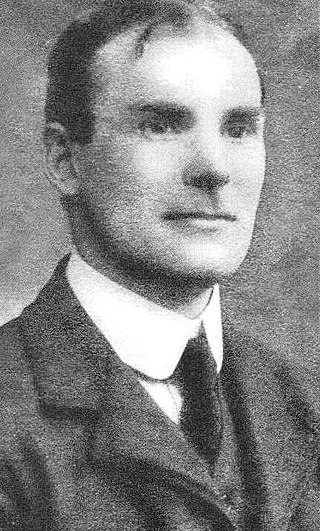

William Walter Gill (1876–1963) was a Manx scholar, folklorist and poet. He is best remembered for his three volumes of A Manx Scrapbook.

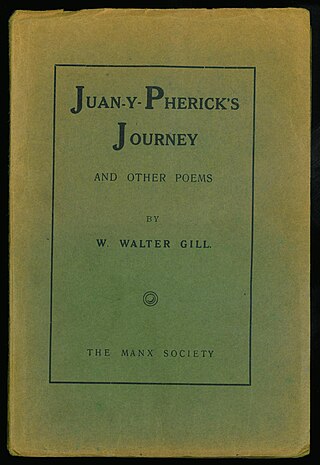

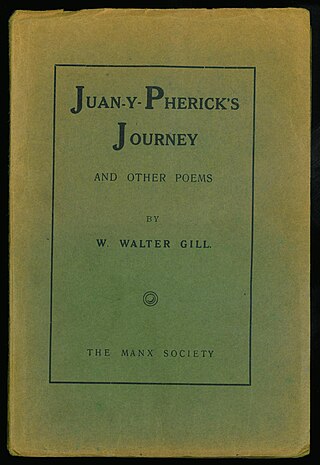

Juan-y-Pherick's Journey and Other Poems is a 1916 collection of poems by W. Walter Gill. The book was published by Yn Çheshaght Gailckagh, the Manx Society, and is Gill's only collection. It is a significant contribution to the literature of the Isle of Man, as there are few other individual poetry collections from this period.

Aeglagh Vannin was a youth group in the Isle of Man whose purpose was the engagement with and revitalisation of Manx language, history and culture. It was established by Mona Douglas in 1931, went through a number of mutations, and faded out in the 1970s. It is best remembered for its central role in the revival of Manx folk dancing.

Colin Jerry was a Manx cultural activist best known for his contributions to Manx music through his books, Kiaull yn Theay, published in two volumes. He was awarded the Reih Bleeaney Vanannan in 1991 for his contributions to Manx culture which were 'extensive and staggering.'

The Peel Players were an amateur theatre group from the Isle of Man in operation during the 1910s and specialising in Anglo-Manx dialect productions.

Yn Çheshaght Ghailckagh, also known as the Manx Language Society and formerly known as Manx Gaelic Society, was founded in 1899 in the Isle of Man to promote the Manx language. The group's motto is Gyn çhengey, gyn çheer.

John Gell, also known as Jack Gell or Juan y Geill was a Manx speaker, teacher, and author who was involved with the revival of the Manx Language on the Isle of Man in the 20th century. His book Conversational Manx, A Series of Graded Lessons in Manx and English, with Phonetic Pronunciation has been used by learners of the Manx language since it was published in 1953.

Edmund Evans Greaves Goodwin was a Manx language scholar, linguist, and teacher. He is best known for his work First Lessons in Manx that he wrote to accompany the classes he taught in Peel.

Doug Fargher also known as Doolish y Karagher or Yn Breagagh, was a Manx language activist, author, and radio personality who was involved with the revival of the Manx language on the Isle of Man in the 20th century. He is best known for his English-Manx Dictionary (1979), the first modern dictionary for the Manx language. Fargher was involved in the promotion of Manx language, culture and nationalist politics throughout his life.

Charles Craine (1911-1979) also known as Chalse y Craayne, was a Manx language activist and teacher who was involved with the revival of the Manx language on the Isle of Man in the 20th century.

John William Radcliffe, more commonly known as Bill Radcliffe, or also Illiam y Radlagh, was a Manx language activist, author, and teacher who was involved with the revival of the Manx language on the Isle of Man in the 20th century. His work recording the last native speakers of the language with the Irish Folklore Commission helped to ensure that a spoken record of the Manx language survived.

Leslie Quirk, also known as Y Kione Jiarg, was a Manx language activist and teacher who was involved with the language's revival on the Isle of Man in the 20th century. His work recording the last native speakers of the language with the Irish Folklore Commission and the Manx Museum helped to ensure that a spoken record of the Manx language survived.