Maud Leonora Menten was a Canadian physician and chemist. As a bio-medical and medical researcher, she made significant contributions to enzyme kinetics and histochemistry, and invented a procedure that remains in use. She is primarily known for her work with Leonor Michaelis on enzyme kinetics in 1913. The paper has been translated from its written language of German into English.

Carrie Chapman Catt was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt served as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1900 to 1904 and 1915 to 1920. She founded the League of Women Voters in 1920 and the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in 1904, which was later named International Alliance of Women. She "led an army of voteless women in 1919 to pressure Congress to pass the constitutional amendment giving them the right to vote and convinced state legislatures to ratify it in 1920". She "was one of the best-known women in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century and was on all lists of famous American women."

Janet Davison Rowley was an American human geneticist and the first scientist to identify a chromosomal translocation as the cause of leukemia and other cancers, thus proving that cancer is a genetic disease. Rowley spent the majority of her life working in Chicago and received many awards and honors throughout her life, recognizing her achievements and contributions in the area of genetics.

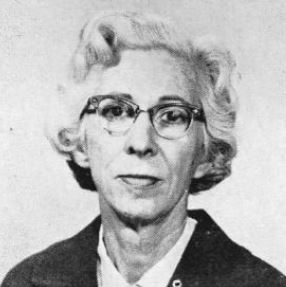

Florence Barbara Seibert was an American biochemist. She is best known for identifying the active agent in the antigen tuberculin as a protein, and subsequently for isolating a pure form of tuberculin, purified protein derivative (PPD), enabling the development and use of a reliable TB test. Seibert has been inducted into the Florida Women's Hall of Fame and the National Women's Hall of Fame.

Claudia Joan Alexander was a Canadian-born American research scientist specializing in geophysics and planetary science. She worked for the United States Geological Survey and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. She was the last project manager of NASA's Galileo mission to Jupiter and until the time of her death had served as project manager and scientist of NASA's role in the European-led Rosetta mission to study Comet Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

Elaine V. Fuchs is an American cell biologist known for her work on the biology and molecular mechanisms of mammalian skin and skin diseases, who helped lead the modernization of dermatology. Fuchs pioneered reverse genetics approaches, which assess protein function first and then assess its role in development and disease. In particular, Fuchs researches skin stem cells and their production of hair and skin. She is an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Rebecca C. Lancefield Professor of Mammalian Cell Biology and Development at The Rockefeller University.

Grace Raymond Hebard was an American historian, suffragist, scholar, writer, political economist, and noted University of Wyoming educator. Hebard's standing as a historian in part rose from her years trekking Wyoming's high plains and mountains seeking first-hand accounts of Wyoming's early pioneers. Today, her books on Wyoming history are sometimes challenged due to her romanticization of the Old West, spurring questions regarding accuracy of her research findings. In particular, her conclusion after decades of field research that Sacajawea was buried in Wyoming's Wind River Indian Reservation is questioned.

Sarah Elizabeth Stewart was a Mexican-American researcher who pioneered the field of viral oncology research, and the first to show that cancer-causing viruses can spread from animal to animal. She and Bernice Eddy co-discovered the first polyoma virus, and SE (Stewart-Eddy) polyoma virus is named after them.

Maud Cuney Hare was an American pianist, musicologist, writer, and African-American activist in Boston, Massachusetts in the United States. She was born in Galveston, the daughter of famed civil rights leader Norris Wright Cuney, who led the Texas Republican Party during and after the Reconstruction Era, and his wife Adelina, a schoolteacher. In 1913 Cuney-Hare published a biography of her father.

The Women's Centennial Congress was organized by Carrie Chapman Catt and held at the Astor Hotel on November 25-27, 1940, to celebrate a century of female progress.

Kamal Jayasing Ranadive was an Indian biomedical researcher known for her research on the links between cancers and viruses. She was a founding member of the Indian Women Scientists' Association (IWSA).

Abbie E. C. Lathrop was a rodent fancier and commercial breeder who bred fancy mice and inbred strains for animal models, particularly for research on development and hereditary properties of cancer.

Mary Cynthia Dickerson was an American herpetologist and the first curator of herpetology at the American Museum of Natural History, as well as the first curator in the now defunct department of Woods and Forestry. For ten years she was the editor of The American Museum Journal, which was renamed Natural History during her editorship. She published two books: Moths and Butterflies (1901) and The Frog Book (1906) as well as numerous popular and scientific articles. She described over 20 species of reptiles and is commemorated in the scientific names of four lizards.

Lilian Jane Gould (1861–1936), also known as Lilian J. Veley, was a British biologist mainly known for her studies of microorganisms in liquor. She was one of the first women admitted to the Linnaean Society. Apart from her scientific work, she was one of the first European breeders of Siamese cats.

Alda Heaton Wilson (1873–1960) was an architect and civil engineer from Iowa. She and her sister Elmina were the first American women to practice civil engineering after obtaining a four-year degree. She worked as a freelance architect in Illinois, Iowa and Missouri before moving to New York and working there for over a decade. She was the first woman supervisor of the women's drafting department of the Iowa Highway Commission. In her later career, she curtailed her architectural works, becoming the secretary, housemate and traveling companion of Carrie Chapman Catt.

Mary Garrett Hay was an American suffragist and community organizer. She served as president of the Women's City Club of New York, the Woman Suffrage Party and the New York Equal Suffrage League. Hay was known for creating woman's suffrage groups across the country. She was also close to the notable suffragist, Carrie Chapman Catt, with one contemporary, Rachel Foster Avery, stating that Hay "really loves" Catt.

Thelma Flournoy Brumfield Dunn was a medical researcher whose work on mice led to significant advances in human cancer research.

Paula Hertwig was a German biologist and politician. Her research focused on radiation health effects. Hertwig was the first woman to habilitate at the then Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin in the field of zoology. She was also the first biologist at a German university. Hertwig is one of the founders of radiation genetics alongside Emmy Stein. Hertwig-Weyers syndrome, which describes oligodactyly in humans as a result of radiation exposure, is named after her and her colleague, Helmut Weyers.

Margaret Georgia Kelly was an American pharmacologist specialized in the pharmacology of drugs used in cancer chemotherapy, carcinogenesis, and chemical protection against radiation and alkylating agents. Kelly was a senior investigator in the National Cancer Institute's laboratory of chemical pharmacology.

Ruth May Tunnicliff was an American physician, medical researcher, bacteriologist, and pathologist, based in Chicago. She developed a serum against measles, and did laboratory research for the United States Army during the 1918 influenza pandemic.