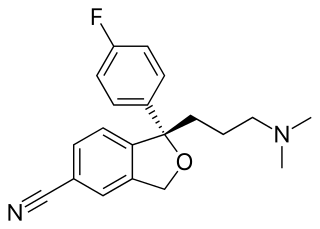

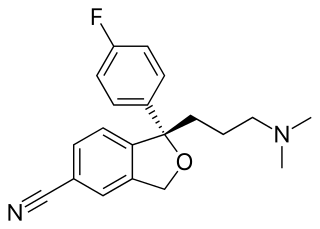

Escitalopram, sold under the brand names Lexapro and Cipralex, among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. Escitalopram is mainly used to treat major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. It is taken by mouth, available commercially as an oxalate salt exclusively.

Citalopram, sold under the brand name Celexa among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. It is used to treat major depressive disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, panic disorder, and social phobia. The antidepressant effects may take one to four weeks to occur. It is typically taken orally. In some European countries, it is sometimes given intravenously to initiate treatment, before switching to the oral route of administration for continuation of treatment. It has also been used intravenously in other parts of the world in some other circumstances.

A generic drug is a pharmaceutical drug that contains the same chemical substance as a drug that was originally protected by chemical patents. Generic drugs are allowed for sale after the patents on the original drugs expire. Because the active chemical substance is the same, the medical profile of generics is equivalent in performance compared to their performance at the time when they were patented drugs. A generic drug has the same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) as the original, but it may differ in some characteristics such as the manufacturing process, formulation, excipients, color, taste, and packaging.

Prescription drug list prices in the United States continually are among the highest in the world. The high cost of prescription drugs became a major topic of discussion in the 21st century, leading up to the American health care reform debate of 2009, and received renewed attention in 2015. One major reason for high prescription drug prices in the United States relative to other countries is the inability of government-granted monopolies in the American health care sector to use their bargaining power to negotiate lower prices, and the American payer ends up subsidizing the world's R&D spending on drugs.

An orphan drug is a pharmaceutical agent that is developed to treat certain rare medical conditions. An orphan drug would not be profitable to produce without government assistance, due to the small population of patients affected by the conditions. The conditions that orphan drugs are used to treat are referred to as orphan diseases. The assignment of orphan status to a disease and to drugs developed to treat it is a matter of public policy that depends on the legislation of the country.

The pharmaceutical industry is an industry involved in medicine that discovers, develops, produces, and markets pharmaceutical goods for use as drugs that function by being administered to patients using such medications with the goal of curing and/or preventing disease. Pharmaceutical companies may deal in "generic" medications and medical devices without the involvement of intellectual property, in "brand" materials specifically tied to a given company's history, or in both within different contexts. The industry's various subdivisions are all subject to a variety of laws and regulations that govern entire financial processes including the patenting, efficacy testing, safety evaluation, and marketing of these drugs. The global pharmaceuticals market produced treatments worth $1,228.45 billion in 2020, in total, and this showed a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 1.8% given the results of recent events.

Aciclovir, also known as acyclovir, is an antiviral medication. It is primarily used for the treatment of herpes simplex virus infections, chickenpox, and shingles. Other uses include prevention of cytomegalovirus infections following transplant and severe complications of Epstein–Barr virus infection. It can be taken by mouth, applied as a cream, or injected.

Etanercept, sold under the brand name Enbrel among others, is a biologic medical product that is used to treat autoimmune diseases by interfering with tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a soluble inflammatory cytokine, by acting as a TNF inhibitor. It has US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval to treat rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and psoriatic arthritis, plaque psoriasis and ankylosing spondylitis. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) is the "master regulator" of the inflammatory (immune) response in many organ systems. Autoimmune diseases are caused by an overactive immune response. Etanercept has the potential to treat these diseases by inhibiting TNF-alpha.

Cetuximab, sold under the brand name Erbitux, is an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor medication used for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer and head and neck cancer. Cetuximab is a chimeric (mouse/human) monoclonal antibody given by intravenous infusion.

Adalimumab, sold under the brand name Humira and others, is a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug and monoclonal antibody used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, plaque psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa, and uveitis. It is administered by subcutaneous injection. It works by inactivating tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα).

A biopharmaceutical, also known as a biological medical product, or biologic, is any pharmaceutical drug product manufactured in, extracted from, or semisynthesized from biological sources. Different from totally synthesized pharmaceuticals, they include vaccines, whole blood, blood components, allergenics, somatic cells, gene therapies, tissues, recombinant therapeutic protein, and living medicines used in cell therapy. Biologics can be composed of sugars, proteins, nucleic acids, or complex combinations of these substances, or may be living cells or tissues. They are isolated from living sources—human, animal, plant, fungal, or microbial. They can be used in both human and animal medicine.

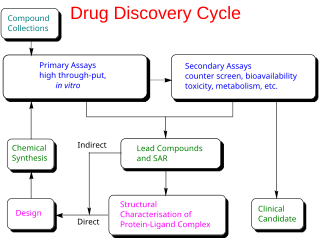

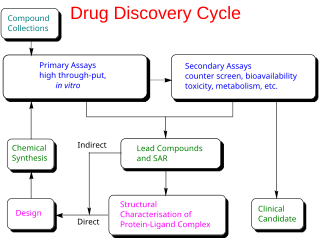

Drug development is the process of bringing a new pharmaceutical drug to the market once a lead compound has been identified through the process of drug discovery. It includes preclinical research on microorganisms and animals, filing for regulatory status, such as via the United States Food and Drug Administration for an investigational new drug to initiate clinical trials on humans, and may include the step of obtaining regulatory approval with a new drug application to market the drug. The entire process—from concept through preclinical testing in the laboratory to clinical trial development, including Phase I–III trials—to approved vaccine or drug typically takes more than a decade.

Evergreening is any of various legal, business, and technological strategies by which producers extend the lifetime of their patents that are about to expire in order to retain revenues from them. Often the practice includes taking out new patents, or by buying out or frustrating competitors, for longer periods of time than would normally be permissible under the law. Robin Feldman, a law professor at UC Law SF and a leading researcher in intellectual property and patents, defines evergreening as "artificially extending the life of a patent or other exclusivity by obtaining additional protections to extend the monopoly period."

Medication costs, also known as drug costs are a common health care cost for many people and health care systems. Prescription costs are the costs to the end consumer. Medication costs are influenced by multiple factors such as patents, stakeholder influence, and marketing expenses. A number of countries including Canada, parts of Europe, and Brazil use external reference pricing as a means to compare drug prices and to determine a base price for a particular medication. Other countries use pharmacoeconomics, which looks at the cost/benefit of a product in terms of quality of life, alternative treatments, and cost reduction or avoidance in other parts of the health care system. Structures like the UK's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and to a lesser extent Canada's Common Drug Review evaluate products in this way.

Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Limited is an Indian multinational pharmaceutical company headquartered in Mumbai, India.

Sarfaraz Khan Niazi he migrated to Karachi, Pakistan in 1962, and to the United States in 1970. He is an expert in biopharmaceutical manufacturing and has worked in academia, industry, and as an entrepreneur. He has written books in pharmaceutical sciences, biotechnology, consumer healthcare, and poetry. He has translated ghazals of the Urdu poet Ghalib.

The Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act of 2012 (FDASIA) is a piece of American regulatory legislation signed into law on July 9, 2012. It gives the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) the authority to collect user fees from the medical industry to fund reviews of innovator drugs, medical devices, generic drugs and biosimilar biologics. It also creates the breakthrough therapy designation program and extends the priority review voucher program to make eligible rare pediatric diseases. The measure was passed by 96 senators voting for and one voting against.

Pharmaceutical innovations are currently guided by a patent system, the patent system protects the innovator of medicines for a period of time. The patent system does not currently stimulate innovation or pricing that provides access to medicine for those who need it the most, It provides for profitable innovation. As of 2014 about $140 Billion is spent on research and development of pharmaceuticals which produces 25–35 new drugs annually. Technology, which is transforming science, medicine, and research tools has increased the speed at which we can analyze data but we currently still must test the products which is a lengthy process. Differences in the performance of medical care may be due to variation in the introduction and circulation of pharmaceutical innovations.

The cost of drug development is the full cost of bringing a new drug to market from drug discovery through clinical trials to approval. Typically, companies spend tens to hundreds of millions of U.S. dollars on drug development. One element of the complexity is that the much-publicized final numbers often not only include the out-of-pocket expenses for conducting a series of Phase I-III clinical trials, but also the capital costs of the long period during which the company must cover out-of-pocket costs for preclinical drug discovery. Additionally, companies often do not report whether a given figure includes the capitalized cost or comprises only out-of-pocket expenses, or both.

A chiral switch is a chiral drug that has already approved as racemate but has been re-developed as a single enantiomer. The term chiral switching was introduced by Agranat and Caner in 1999 to describe the development of single enantiomers from racemate drugs. For example, levofloxacin is a chiral switch of racemic ofloxacin. The essential principle of a chiral switch is that there is a change in the status of chirality. In general, the term chiral switch is preferred over racemic switch because the switch is usually happening from a racemic drug to the corresponding single enantiomer(s). It is important to understand that chiral switches are treated as a selection invention. A selection invention is an invention that selects a group of new members from a previously known class on the basis of superior properties. To express the pharmacological activities of each of the chiral twins of a racemic drug two technical terms have been coined eutomer and distomer. The member of the chiral twin that has greater physiological activity is referred to as the eutomer and the other one with lesser activity is referred to as distomer. The eutomer/distomer ratio is called the eudisimic ratio and reflects the degree of enantioselectivity of the biological activity.