Related Research Articles

The DPT vaccine or DTP vaccine is a class of combination vaccines against three infectious diseases in humans: diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus. The vaccine components include diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and either killed whole cells of the bacterium that causes pertussis or pertussis antigens. The term toxoid refers to vaccines which use an inactivated toxin produced by the pathogen which they are targeted against in order to generate an immune response. In this way, the toxoid vaccine generates an immune response which is targeted against the toxin which is produced by the pathogen and causes disease, rather than a vaccine which is targeted against the pathogen itself. The whole cells or antigens will be depicted as either "DTwP" or "DTaP", where the lower-case "w" indicates whole-cell inactivated pertussis and the lower-case "a" stands for “acellular”. In comparison to alternative vaccine types, such as live attenuated vaccines, the DTP vaccine does not contain the pathogen itself, but rather uses inactivated toxoid to generate an immune response; therefore, there is not a risk of use in populations that are immune compromised since there is not any known risk of causing the disease itself. As a result, the DTP vaccine is considered a safe vaccine to use in anyone and it generates a much more targeted immune response specific for the pathogen of interest. However, booster doses are recommended every ten years to maintain immune protection against these pathogens.

MeNZB was a vaccine against a specific strain of group B meningococcus, used to control an epidemic of meningococcal disease in New Zealand. Most people are able to carry the meningococcus bacteria safely with no ill effects. However, meningococcal disease can cause meningitis and sepsis, resulting in brain damage, failure of various organs, severe skin and soft-tissue damage, and death.

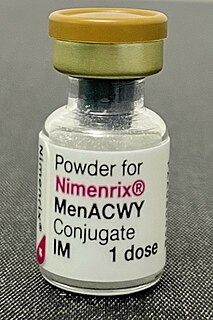

A conjugate vaccine is a type of subunit vaccine which combines a weak antigen with a strong antigen as a carrier so that the immune system has a stronger response to the weak antigen.

Neisseria meningitidis, often referred to as meningococcus, is a Gram-negative bacterium that can cause meningitis and other forms of meningococcal disease such as meningococcemia, a life-threatening sepsis. The bacterium is referred to as a coccus because it is round, and more specifically a diplococcus because of its tendency to form pairs.

Meningococcal disease describes infections caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis. It has a high mortality rate if untreated but is vaccine-preventable. While best known as a cause of meningitis, it can also result in sepsis, which is an even more damaging and dangerous condition. Meningitis and meningococcemia are major causes of illness, death, and disability in both developed and under-developed countries.

PATH is an international, nonprofit global health organization based in Seattle, with 1,600 employees in more than 70 countries around the world. Its president and CEO is Nikolaj Gilbert, who is also the Managing Director and CEO of Foundations for Appropriate Technologies in Health (FATH), PATH's Swiss subsidiary. PATH focuses on six platforms—vaccines, drugs, diagnostics, devices, system, and service innovations—to develop innovations and implement solutions that save lives and improve health.

George D. Heist (1886–1920) was an immunologist specializing in the study of infections of meningococcal bacteria that often result in meningococcal disease, which is well known as highly lethal and debilitating, and extremely difficult to treat.

The Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine, also known as Hib vaccine, is a vaccine used to prevent Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infection. In countries that include it as a routine vaccine, rates of severe Hib infections have decreased more than 90%. It has therefore resulted in a decrease in the rate of meningitis, pneumonia, and epiglottitis.

JN-International Medical Corporation (JNIMC) is a U.S.-based biopharmaceutical corporation which since 1998 has been focused on developing vaccines and diagnostics for infectious disease for developing countries. This private corporation was founded in 1998 by Dr. Jeeri R. Reddy with the help of Dr. Kelly F. Lechtenberg in a small rural town, Oakland, Nebraska. From there it grew and expanded until in the year 2000 the corporation moved to Omaha, Nebraska.

NmVac4-A/C/Y/W-135 is the commercial name of the polysaccharide vaccine against the bacterium that causes meningococcal meningitis. The product, by JN-International Medical Corporation, is designed and formulated to be used in developing countries for protecting populations during meningitis disease epidemics.

Jeeri Reddy an American biologist who became an entrepreneur, developing new generation preventive and therapeutic vaccines. He has been an active leader in the field of the biopharmaceutical industry, commercializing diagnostics and vaccines through JN-International Medical Corporation. He is the scientific director and president of the corporation that created the world's first serological rapid tests for Tuberculosis to facilitate acid-fast bacilli microscopy for the identification of smear-positive and negative cases. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV was achieved in South East Asia by the use of rapid tests developed by Reddy in 1999. Reddy through his Corporation donated $173,050 worth of Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) for malaria in Zambia and actively participated in the prevention of child deaths due to Malaria infections. Reddy was personally invited by the president, George W. Bush, and First Lady Laura Bush to the White House for Malaria Awareness Day sponsored by US President Malaria Initiative (PMI) on Wednesday, April 25, 2007.

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or altered consciousness, nausea, vomiting, and an inability to tolerate light or loud noises. Young children often exhibit only nonspecific symptoms, such as irritability, drowsiness, or poor feeding. A non-blanching rash may also be present.

Niger is a landlocked country located in West Africa and has Libya, Chad, Nigeria, Benin, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Algeria as its neighboring countries. Niger was French territory that its independence in 1960 and its official language is French. Niger has an area of 1.267 million square kilometres, nevertheless, 80% of its land area spreads through the Sahara Desert.

Meningococcal vaccine refers to any vaccine used to prevent infection by Neisseria meningitidis. Different versions are effective against some or all of the following types of meningococcus: A, B, C, W-135, and Y. The vaccines are between 85 and 100% effective for at least two years. They result in a decrease in meningitis and sepsis among populations where they are widely used. They are given either by injection into a muscle or just under the skin.

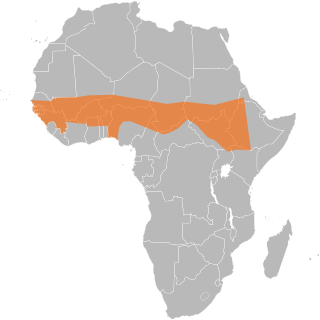

The African meningitis belt is a region in sub-Saharan Africa where the rate of incidence of meningitis is very high. It extends from Senegal to Ethiopia, and the primary cause of meningitis in the belt is Neisseria meningitidis.

The Meningitis Vaccine Project is an effort to eliminate the meningitis epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa by developing a new meningococcal vaccine. The meningitis problem in that area is caused by a strain of meningitis called "meningitis A", which is present only in the African meningitis belt. In June 2010 various sources announced that they had developed MenAfriVac, which is an inexpensive, safe, and highly effective vaccine which is likely to stop the epidemic as quickly as anyone had ever hoped that it would.

Tetanus vaccine, also known as tetanus toxoid (TT), is a toxoid vaccine used to prevent tetanus. During childhood, five doses are recommended, with a sixth given during adolescence.

Sir Andrew John Pollard is a Professor of Paediatric Infection and Immunity at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of St Cross College, Oxford. He is an Honorary Consultant Paediatrician at John Radcliffe Hospital and the Director of the Oxford Vaccine Group. He is the Chief Investigator on the University of Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine trials and has led research on vaccines for many life-threatening infectious diseases including typhoid fever, Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae type b, streptococcus pneumoniae, pertussis, influenza, rabies, and Ebola.

Diana Rae Martin was a New Zealand microbiologist. She was a Fellow of the Royal Society Te Apārangi from 2000, and was made an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to microbiology in 2008.

References

- ↑ World Health Organization (November 2011). "Meningococcal vaccines. World Health Organization position paper, November 2011" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ↑ World Health Organization (February 2015). "Meningococcal A conjugate vaccine: updated guidance. World Health Organization" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ↑ "Improved meningitis vaccine for Africa could signal eventual end to deadly scourge". 8 June 2007. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ↑ "The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Announces Grant for the Elimination of Epidemic Meningitis in Sub-Saharan Africa". Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. May 30, 2001. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ↑ "WHO weekly epidemiology record" (PDF). World Health Organization. September 16, 2005. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ↑ Anderson, Tatum (14 October 2010). "Africa hails new meningitis vaccine". 14 October 2010. BBC News. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ↑ MSF: 50 Years of Vaccination History

- 1 2 Press Release (12 September 2013). "Vaccine campaign in sub-Saharan Africa reduces meningitis by 94 per cent". Wellcome Trust. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- 1 2 Greenwood, BM; Daugla, DM; Gami, JP; Gamougam, K; Naibei, N; MBainadji, L; Narbe, M; Toralta, J; et al. (12 September 2013). "Effect of a serogroup A meningococcal conjugate vaccine (PsA-TT) on serogroup A meningococcal meningitis and carriage in Chad: a community trial". The Lancet. 383 (9911): 40–47. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61612-8. PMC 3898950 . PMID 24035220.

- 1 2 3 "Knockout jab". The Economist. November 14, 2015. ISSN 0013-0613 . Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- ↑ "The Meningitis Vaccine Project: The Development, Licensure, Introduction, and Impact of a New Group A Meningococcal Conjugate Vaccine for Africa". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 61 (suppl_5): 673.1–673. 2016. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ1186 .

- ↑ "MenAfriVac Meningococcal A Conjugate Vaccine". seruminstitute.com. Serum Institute of India. 2011. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.