Related Research Articles

Steinbach is the third-largest city in the province of Manitoba, Canada, and with a population of 17,806, the largest community in the Eastman region. The city, located about 58 km (36 mi) southeast of the provincial capital of Winnipeg, is bordered by the Rural Municipality of Hanover to the north, west, and south, and the Rural Municipality of La Broquerie to the east. Steinbach was first settled by Plautdietsch-speaking Mennonites from Ukraine in 1874, whose descendants continue to have a significant presence in the city today. Steinbach is found on the eastern edge of the Canadian Prairies, while Sandilands Provincial Forest is a short distance east of the city.

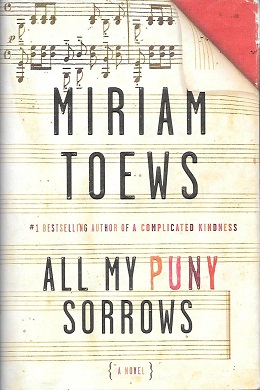

Miriam Toews is a Canadian writer and author of nine books, including A Complicated Kindness (2004), All My Puny Sorrows (2014), and Women Talking (2018). She has won a number of literary prizes including the Governor General's Award for Fiction and the Writers' Trust Engel/Findley Award for her body of work. Toews is also a three-time finalist for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and a two-time winner of the Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize.

A Complicated Kindness (2004) is the third novel by Canadian author Miriam Toews. The novel won the Governor General's Award for English Fiction, the CBA Libris Fiction Award, and CBC's Canada Reads.

Klaas Reimer (1770–1837) was the founder of the Kleine Gemeinde, a Mennonite denomination that still exists in Latin America, but underwent radical changes in Canada where it is now called the Evangelical Mennonite Conference. Ethnic Mennonite remigrants from Latin America brought the original Kleine Gemeinde back to Canada and the US.

Mennonite Heritage Village is a museum in Steinbach, Manitoba, Canada telling the story of the Low German Mennonites in Canada. The museum contains both an open-air museum open seasonally, and indoor galleries open year-round. Opened in 1967 and expanded significantly since then, the Mennonite Heritage Village is a major tourist attraction in the area and officially designated as a Manitoba Signature Museum and Star Attraction. Approximately 47,000 visitors visit the museum each year.

Armin Wiebe is a Canadian writer from Winnipeg, Manitoba, best known for his humorous novels about Mennonites. Wiebe is regarded as one of the pioneers of humorous Mennonite writing in English and is known for his incorporation of Plautdietsch words within his English texts.

Kleine Gemeinde is a Mennonite denomination founded in 1812 by Klaas Reimer in the Russian Empire. The current group primarily consists of Plautdietsch-speaking Russian Mennonites in Belize, Mexico and Bolivia, as well as a small presence in Canada and the United States. In 2015 it had some 5,400 baptized members. Most of its Canadian congregations diverged from the others over the latter half of the 20th century and are now called the Evangelical Mennonite Conference.

Turnstone Press is a Canadian literary publisher founded in 1976 in Winnipeg, Manitoba, the oldest in Manitoba and among the most respected independent publishers in Canada.

Irma Voth (2011) is the fifth novel by Canadian author Miriam Toews. The novel, about a Mennonite teenager whose life is transformed when a bohemian film crew comes to her settlement to make a film about Mennonites, was informed by Toews' experience as lead actress in Silent Light, the award-winning 2007 film written and directed by Mexican filmmaker Carlos Reygadas.

All My Puny Sorrows is the sixth novel by Canadian writer Miriam Toews. The novel won the 2014 Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize, and was shortlisted for the 2014 Scotiabank Giller Prize, the 2015 Folio Prize for Literature, and the 2015 Wellcome Book Prize. Toews has said that the novel draws heavily on the events leading up to the 2010 suicide of her sister, Marjorie.

Casey Plett is a Canadian writer, best known for her novel Little Fish, her Lambda Literary Award winning short story collection, A Safe Girl to Love, and her Giller Prize-nominated short story collection, A Dream of a Woman. Plett is a transgender woman, and she often centers this experience in her writing.

The Daily Bonnet is a satirical Mennonite website, known as The Unger Review as of 2023. It was created by Andrew Unger and launched in May 2016. It features news stories and editorials, with the structure of conventional newspapers, but whose content is contorted to make humorous commentary on Mennonite and Anabaptist issues.

John Peter Thiessen was a Canadian Russian Mennonite teacher, translator, and writer from Manitoba. Alongside Arnold Dyck and Reuben Epp, he was an important contributor to the development of Mennonite Low German literature, as well as one of the language's most prominent lexicographers.

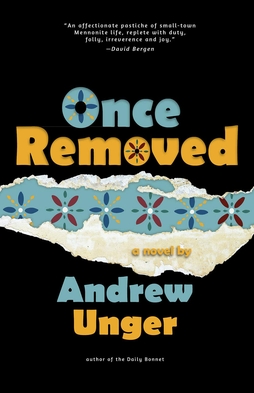

Andrew Unger is a Canadian novelist and satirist. He is the author of the satirical news website The Unger Review, as well as the novel Once Removed and the collection The Best of the Bonnet.

Elmer E. 'Al' Reimer (1927–2015) was a Mennonite writer from Steinbach, Manitoba. Reimer was an important literary critic and writer in the emergence of southern Manitoba Mennonite literature during the 1970s and 80s. Born in Landmark, Manitoba, Reimer grew up in Steinbach and received his PhD at Yale University. He taught English literature at University of Winnipeg for many years.

Women Talking (2018) is the seventh novel by Canadian writer Miriam Toews. Toews describes her novel as "an imagined response to real events," the gas-facilitated rapes that took place on the Manitoba Colony, a remote and isolated Mennonite community in Bolivia: Between 2005 and 2009, over a hundred girls and women in the colony woke up to discover that they had been raped in their sleep. These nighttime attacks were denied or dismissed by colony elders until finally it was revealed that a group of men from the colony were spraying an animal anaesthetic into their victims' houses to render them unconscious. Toews' novel centers on the secret meetings of eight Mennonite women who, on behalf of the other women in the colony, must decide how to react to these traumatic events. They have only 48 hours before the colony men, who are away to post bail for the rapists, return.

David Elias is a Canadian writer from Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Once Removed is a novel by Canadian author Andrew Unger published in 2020. Published by Turnstone Press, the book is a satire set in the fictional town of Edenfeld, Manitoba and tells the story of Timothy Heppner, a ghostwriter trying to preserve the history of his small Mennonite town.

East Village is a fictional town in the Canadian province of Manitoba, frequently used as a setting in novels by Miriam Toews. The town was based on Toews's real-life hometown of Steinbach. East Village appears in A Complicated Kindness and All My Puny Sorrows as well as the film adaptation of All My Puny Sorrows. Toews also refers to Steinbach in Fight Night and her nonfiction work Swing Low.

References

- ↑ Alex Dye (2012-04-09). "Mennonite literature as genre". Englewood Review of Books. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ Robert Zacharias (2015). After Identity: Mennonite Writing in North America. University of Manitoba Press.

- ↑ Magdalene Redekop (2020). Making Believe:Questions About Mennonites and Art. University of Manitoba Press.

- ↑ Elizabeth Horsch Bender and Harry Loewen. "Literature, Mennonites (1895-1980s)". GAMEO. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ Erwin Beck. Mennonite transgressive literature. Mennonite Quarterly Review.

- ↑ Magdalene Redekop (2020). Making Believe:Questions About Mennonites and Art. University of Manitoba Press.

- ↑ "The gap in Mennonite literature". The Canadian Mennonite. 2011-09-21. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ "From Plain People to Plains People: Mennonite Literature from the Canadian Prairies". American Studies Journal. 17 October 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ Weaver-Zercher, Valerie (6 June 2013). "Why Amish Romance Novels Are Hot". The Wall Street Journal . Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ↑ The Old World and the New:Literary Perspectives of German-speaking Canadians. University of Toronto Press. 1984.

- 1 2 3 "Literature, North American Mennonite". GAMEO. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ Magdalene Redekop (2020). Making Believe:Questions About Mennonites and Art. University of Manitoba Press.

- ↑ Alex Dye (2012-04-09). "Mennonite literature as genre". Englewood Review of Books. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ David Arnason. "Telling Our Own Stories" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-26. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Rhubarb runs out". Canadian Mennonite. 2018-07-18. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ Rudy Wiebe's entry in The Canadian Encyclopedia

- ↑ "Literature, North American Mennonite". GAMEO. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ Baillie, Andrea (7 December 2004). "Strong year for Canadian fiction as Munro receives raves, Toews triumphs". Canadian Press Newswire.

- ↑ The Canadian Encyclopedia

- ↑ Groskop, Viv (9 January 2011). "Mennonite in a Little Black Dress". The Guardian. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Humor". GAMEO. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ Huber, Tim (July 4, 2016). "Satire news site pokes fun at Mennonite quirks". Mennonite World Review. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ↑ Schwartz, Alexandra (March 25, 2019). "A Beloved Canadian Novelist Reckons with Her Mennonite Past". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ↑ "'The Daily Bonnet' creator publishes book". Canadian Mennonite Magazine. 4 November 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ↑ Daniel Shank Cruz. "Introduction:Queer Mennonite Literature" . Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Casey Plett, Joshua Whitehead win 2019 Lambda Literary Awards". CBC. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "A Dream of a Woman". CBC.ca. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ↑ "Mennonite Sci-fi". Point Grey Inter-Mennonite Fellowship.

- ↑ "The White Mosque". Penguin Random House Canada. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ "A Novel That Imagines Motherhood as an Animal State". The New Yorker. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ↑ "How a meeting of Mennonites resulted in an all-time bestselling book" . Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ↑ Will Braun (2018-07-18). "Rhubarb runs out". Canadian Mennonite. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- 1 2 "Center for Mennonite Writing" . Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Lives Lived, Lives Imagined". University of Manitoba Press. Retrieved March 20, 2023.