Georg Simon Ohm was a German physicist and mathematician. As a school teacher, Ohm began his research with the new electrochemical cell, invented by Italian scientist Alessandro Volta. Using equipment of his own creation, Ohm found that there is a direct proportionality between the potential difference (voltage) applied across a conductor and the resultant electric current. This relation is called Ohm's law, and the ohm, the unit of electrical resistance, is named after him.

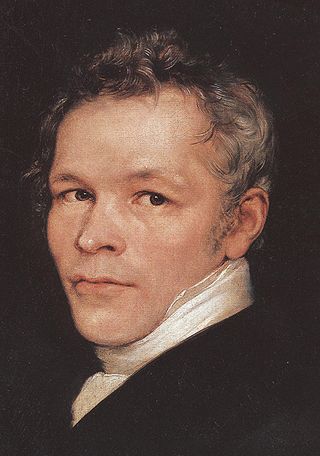

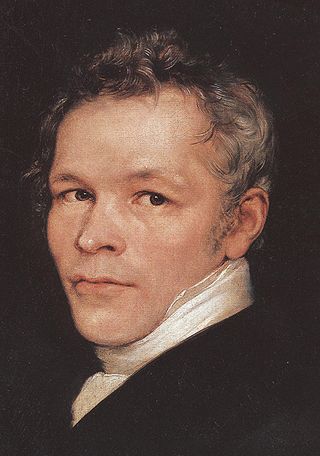

Karl Friedrich Schinkel was a Prussian architect, city planner and painter who also designed furniture and stage sets. Schinkel was one of the most prominent architects of Germany and designed both Neoclassical and neo-Gothic buildings. His most famous buildings are found in and around Berlin.

The Grand Duchy of Posen was part of the Kingdom of Prussia, created from territories annexed by Prussia after the Partitions of Poland, and formally established following the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. Per agreements derived at the Congress of Vienna it was to have some autonomy. However, in reality it was subordinated to Prussia and the proclaimed rights for Polish subjects were not fully implemented. On 9 February 1849, the Prussian administration renamed the grand duchy the Province of Posen. Its former name was unofficially used afterward for denoting the territory, especially by Poles, and today is used by modern historians to refer to different political entities until 1918. Its capital was Posen.

Baron Carl von Rokitansky was an Austrian physician, pathologist, humanist philosopher and liberal politician, founder of the Viennese School of Medicine of the 19th century. He was the founder of science-based diagnostics.

Wilhelmstrasse is a major thoroughfare in the central Mitte and Kreuzberg districts of Berlin, Germany. Until 1945, it was recognised as the centre of the government, first of the Kingdom of Prussia, later of the unified German Reich, housing in particular the Reich Chancellery and the Foreign Office. The street's name was thus also frequently used as a metonym for overall German governmental administration: much as the term "Whitehall" is often used to signify the British governmental administration as a whole. In English, "the Wilhelmstrasse" usually referred to the German Foreign Office.

The Bauakademie in Berlin, Germany, was a higher education institution for the art of building to train master builders. Founded on 18 March 1799 by King Frederick William III, the institution originated from the construction department of the Academy of Fine Arts and Mechanical Sciences, which emphasized the aesthetic elements of the art of building while ignoring the technical. Thus, the governmental Upper Building Department ("UBD") decided to establish an entirely new building educational institution named "Bauakademie". In 1801, the institution was incorporated into the UBD.

The Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences was an academy established in Berlin, Germany on 11 July 1700, four years after the Prussian Academy of Arts, or "Arts Academy," to which "Berlin Academy" may also refer. In the 18th century, when French was the language of science and culture, it was a French-language institution.

The Palais Strousberg was a large city mansion built in Berlin, Germany for the railway magnate Bethel Henry Strousberg. It was designed by the architect August Orth and built between 1867–68 at No.70 Wilhelmstraße. The grandiose splendour of its accommodation and novel integration of the latest building technologies into the fabric of the building, ensured that Berliners would still find the Palais impressive decades after its construction, becoming the model of refined luxury in Berlin architecture.

The Prussian Academy of Arts was a state arts academy first established in Berlin, Brandenburg, in 1694/1696 by prince-elector Frederick III, in personal union Duke Frederick I of Prussia, and later king in Prussia.

Wilhelmplatz was a square in the Mitte district of Berlin, at the corner of Wilhelmstrasse and Voßstraße. The square also gave its name to a Berlin U-Bahn station which has since been renamed Mohrenstraße. A number of notable buildings were constructed around the square, including the old Reich Chancellery, the building of the Ministry of Finance and the Kaiserhof grand hotel built in 1875.

A Kunstgewerbeschule was a type of vocational arts school that existed in German-speaking countries from the mid-19th century. The term Werkkunstschule was also used for these schools. From the 1920s and after World War II, most of them either merged into universities or closed, although some continued until the 1970s.

A Kriegsschule was a general military school used for basic officer training and higher education in Germany starting in as early as the 17th century. There have been many Kriegsakademies, 'Kriegsschulen', or even Ritterakademies in Germany.

Karl Sigmund Franz Freiherr vom Stein zum Altenstein was a Prussian politician and the first Prussian education minister. His most lasting impact was the reform of the Prussian educational system.

The Reich Ministry of Food and Agriculture was responsible for the agricultural policy of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1919 to 1933 and during the Nazi dictatorship of the Third Reich from 1933 to 1945. It was headed by a Reichsminister under whom a state secretary served. On 1 January 1935, the ministry merged with the Prussian Ministry of Agriculture, Domains and Forests, founded in 1879. Until 1938 and the Anschluss with Austria, it was called the "Reich and Prussian Ministry of Food and Agriculture". After the end of National Socialism in 1945 and of the Allied occupation of Germany, the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture was established in 1949 as a successor in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Salomo Sachs was a Jewish Prussian architect, astronomer, Prussian building official, mathematician, drawing teacher for architecture, teacher for machine drawings, building economist, writer, author of non-fiction and textbooks and universal scholar. He attained the rank of a royal building inspector and with his cousin Major Meno Burg they were the only men in the Prussian civil service who had not renounced their Jewish faith.

Georg Thür, complete name Carl Georg Thür, was a German architect and Prussian official builder whose designs for university buildings had a decisive influence on the Prussian university landscape.

The Prussian State Ministry from 1808 to 1850 was the executive body of ministers, subordinate to the King of Prussia and, from 1850 to 1918, the overall ministry of the State of Prussia consisting of the individual ministers. In other German states, it corresponded to the state government or the senate of a free city.

The Ministry of Trade, Commerce and Public Works was a ministry in Prussia that was founded in 1848. Its beginnings date back to 1740. In 1878 it became the Ministry of Trade and Commerce by spinning off the Ministry of Public Works, which was dissolved in 1921; the responsibilities were transferred back to the Ministry of Agriculture, Domains and Forestry and of Trade and Commerce. In 1932 it became the Ministry of Economy and Labor.

The Prussian State Council was an advisory body to the King in the Prussian State from 1817 to 1848 and reactivated in 1854, 1884, and 1895. Its members did not have the title of State Councilor, but were allowed to call themselves a Member of the State Council.