Medieval music consists of songs, instrumental pieces, and liturgical music from about 500 A.D. to 1400. Medieval music was an era of Western music, including liturgical music used for the church, and secular music, non-religious music. Medieval music includes solely vocal music, such as Gregorian chant and choral music, solely instrumental music, and music that uses both voices and instruments. Gregorian chant was sung by monks during Catholic Mass. The Mass is a reenactment of Christ's Last Supper, intended to provide a spiritual connection between man and God. Part of this connection was established through music. This era begins with the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century and ends sometime in the early fifteenth century. Establishing the end of the medieval era and the beginning of the Renaissance music era is difficult, since the trends started at different times in different regions. The date range in this article is the one usually adopted by musicologists.

The time signature is a notational convention used in Western musical notation to specify how many beats (pulses) are contained in each measure (bar), and which note value is equivalent to a beat.

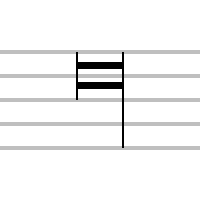

In music, a half note (American) or minim (British) is a note played for half the duration of a whole note and twice the duration of a quarter note. It was given its Latin name because it was the shortest of the five note values used in early medieval music notation. In time signatures with 4 as the bottom number, such as 4

4 or 3

4, the half note is two beats long. However, when 2 is the bottom number, the half note is one beat long.

A whole note (American) or semibreve (British) is a kind of note used in music notation. It has a time duration of four beats in 4

4 time.

Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song in Latin of the Roman Catholic Church. Gregorian chant developed mainly in western and central Europe during the 9th and 10th centuries, with later additions and redactions. Although popular legend credits Pope Gregory I with inventing Gregorian chant, scholars believe that it arose from a later Carolingian synthesis of Roman chant and Gallican chant.

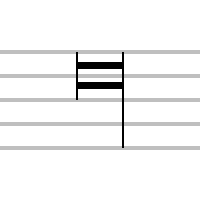

In music, a double whole note (American), breve (international), or double note is a note lasting two times as long as a whole note. It is the second-longest note value still in use in modern music notation.

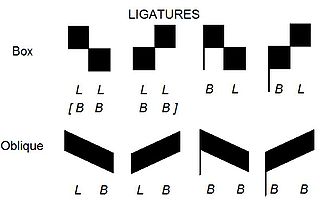

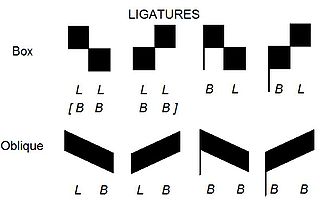

In music notation, a ligature is a graphic symbol that tells a musician to perform two or more notes in a single gesture, and on a single syllable. It was primarily used from around 800 to 1650 AD. Ligatures are characteristic of neumatic (chant) and mensural notation. The notation and meaning of ligatures has changed significantly throughout Western music history, and their precise interpretation is a continuing subject of debate among musicologists.

Organum is, in general, a plainchant melody with at least one added voice to enhance the harmony, developed in the Middle Ages. Depending on the mode and form of the chant, a supporting bass line may be sung on the same text, the melody may be followed in parallel motion, or a combination of both of these techniques may be employed. As no real independent second voice exists, this is a form of heterophony. In its earliest stages, organum involved two musical voices: a Gregorian chant melody, and the same melody transposed by a consonant interval, usually a perfect fifth or fourth. In these cases the composition often began and ended on a unison, the added voice keeping to the initial tone until the first part has reached a fifth or fourth, from where both voices proceeded in parallel harmony, with the reverse process at the end. Organum was originally improvised; while one singer performed a notated melody, another singer—singing "by ear"—provided the unnotated second melody. Over time, composers began to write added parts that were not just simple transpositions, thus creating true polyphony.

Ars antiqua, also called ars veterum or ars vetus, is a term used by modern scholars to refer to the Medieval music of Europe during the High Middle Ages, between approximately 1170 and 1310. This covers the period of the Notre Dame school of polyphony, and the subsequent years which saw the early development of the motet, a highly varied choral musical composition. Usually the term "ars antiqua" is restricted to sacred (church) or polyphonic music, excluding the secular (non-religious) monophonic songs of the troubadours, and trouvères. However, sometimes the term "ars antiqua" is used more loosely to mean all European music of the thirteenth century, and from slightly before. The term ars antiqua is used in opposition to ars nova, which refers to the period of musical activity between approximately 1310 and 1375.

A neume is the basic element of Western and Eastern systems of musical notation prior to the invention of five-line staff notation.

Alla breve[alla ˈbrɛːve] – also known as cut time or cut common time – is a musical meter notated by the time signature symbol , which is the equivalent of 2

2. The term is Italian for "on the breve", originally meaning that the beat was counted on the breve.

In medieval music, the rhythmic modes were set patterns of long and short durations. The value of each note is not determined by the form of the written note, but rather by its position within a group of notes written as a single figure called a "ligature", and by the position of the ligature relative to other ligatures. Modal notation was developed by the composers of the Notre Dame school from 1170 to 1250, replacing the even and unmeasured rhythm of early polyphony and plainchant with patterns based on the metric feet of classical poetry, and was the first step towards the development of modern mensural notation. The rhythmic modes of Notre Dame Polyphony were the first coherent system of rhythmic notation developed in Western music since antiquity.

In music notation, a note value indicates the relative duration of a note, using the texture or shape of the notehead, the presence or absence of a stem, and the presence or absence of flags/beams/hooks/tails. Unmodified note values are fractional powers of two, for example one, one-half, one fourth, etc.

Prolation is a term used in the theory of the mensural notation of medieval and Renaissance music to describe its rhythmic structure on a small scale, as opposed to tempus, which described a larger scale. The term "prolation" is derived from the Latin prolatio, first used by Philippe de Vitry in describing Ars Nova, a musical style that came about in 14th-century France.

Petrus de Cruce was active as a cleric, composer and theorist in the late part of the 13th century. His main contribution was to the notational system.

Mensural notation is the musical notation system used for European vocal polyphonic music from the later part of the 13th century until about 1600. The term "mensural" refers to the ability of this system to describe precisely measured rhythmic durations in terms of numerical proportions between note values. Its modern name is inspired by the terminology of medieval theorists, who used terms like musica mensurata or cantus mensurabilis to refer to the rhythmically defined polyphonic music of their age, as opposed to musica plana or musica choralis, i.e., Gregorian plainchant. Mensural notation was employed principally for compositions in the tradition of vocal polyphony, whereas plainchant retained its own, older system of neume notation throughout the period. Besides these, some purely instrumental music could be written in various forms of instrument-specific tablature notation.

A longa, long, quadruple note (Am.), or quadruple whole note is a musical note that could be either twice or three times as long as a breve, four or six times as long as a semibreve, that appears in early music. The number of breves in a long was determined by the "modus" or "mode" of a passage. Sections in perfect mode used three breves to the long while sections in imperfect mode used two breves to the long. Imperfect longs, worth two breves, existed in perfect mode from the earliest sources, while the fourteenth century saw the introduction of perfect longs, worth three breves, in imperfect mode through the use of dots of addition.

With regard to early polyphony the term copula has a variety of meanings. At its most basic level, it can be thought of as the linking of notes together to form a melody. "A copula is a rapid, connected discant..." However, it is often considered to be a particular type of polyphonic texture similar to organum, but with modal rhythm. The music theorist Johannes de Garlandia favoured this description of copula. The term refers to music where the lower voice sings long, sustained notes while the higher voices sing faster-moving harmony lines. This style is typical of what is referred to as Notre Dame Polyphony; examples of which can be found in the Magnus Liber Organi. Copula might have implied a strophic construction with much repetition in the various parts, which was characteristic of much of the music written in this idiom. The upper part consists of "antecedent-consequent" phrases, themselves featuring much melodic repetition. The rhythm is notated in copula, unlike in organum. It is, in essence, the "coming together" of these two parts at the cadence that led to the term copula being used, from the Latin meaning "that binds."

Theodore Cyrus Karp was an American musicologist. His principal area of study was saecular mediaeval monophony, especially the music of the trouvères. He was a major contributor in this area to the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

A maxima, duplex longa, larga, or octuple whole note was a musical note used commonly in thirteenth and fourteenth century music and occasionally until the end of the sixteenth century. It was usually twice or, rarely, three times as long as a longa, four or six or nine times as long as a breve, and 8, 12, 18, or 27 times as long as a semibreve. Like the stem of the longa, the stem of the maxima generally pointed downwards except occasionally when it appeared on the bottom line or space. Before around 1430, the maxima was written with a solid, black body. Over the course of the fifteenth century, like most other note values, the head of the maxima became void.