The Basij or Niru-ye Moghāvemat-e Basij, full name Sâzmân-e Basij-e Mostaz'afin, is a paramilitary volunteer militia within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and one of its five branches. The force is named Basij; an individual member is called basiji in the Persian language. As of July 2019, Gholamreza Soleimani is the commander of the Basij.

Iran–United Kingdom relations are the bilateral relations between the United Kingdom and Iran. Iran, which was called Persia by the West before 1935, has had political relations with England since the late Ilkhanate period when King Edward I of England sent Geoffrey of Langley to the Ilkhanid court to seek an alliance.

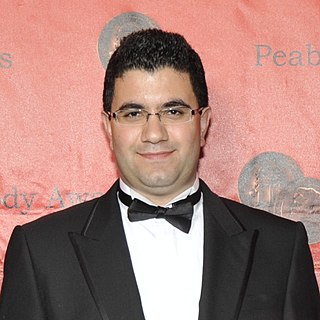

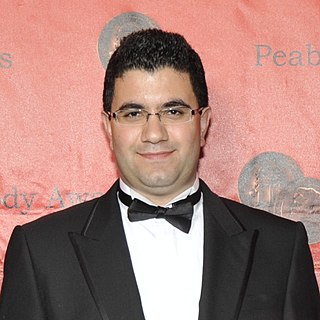

Arash Hejazi, born 1971 in Tehran, Iran, is an Iranian physician, novelist, fiction writer and translator of literary works from English and Portuguese into Persian. He is also an editor in Caravan Books Publishing House (Iran), and Book Fiesta Literary Magazine. He is a member of the Tehran Union of Publishers and Booksellers (TUPB) and was the managing editor of its journal, Sanat-e-Nashr, from 2006 to 2007. He was one of the nominees to receive the Freedom to Publish Prize held by International Publishers’ Association (IPA) in 2006. He is also a novel writer, whose best known novel The Princess of the Land of Eternity was shortlisted for two major Iranian literary prizes and has sold more than 20,000 copies in Iran since its first publication in 2003. He in 2009 he received his MA in Publishing from Oxford Brookes University. His dissertation on censorship in Iran was published in the publishing journal Logos in 2011, and his memoir The Gaze of the Gazelle about growing up in Iran after the Islamic Revolution was published by University of Chicago Press in 2011.

Saeed Kamali Dehghan is an Iranian-British journalist who writes for The Guardian. He was named as the 2010 Journalist of the Year in Britain by the Foreign Press Association. He is a staff journalist for The Guardian working from its London offices, and has been an Iran correspondent from Tehran for the newspaper in the past, especially in summer 2009. He is a co-producer of the 2010 HBO documentary For Neda, which was a recipient of the 70th annual Peabody Award.

After incumbent president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad declared victory in the 2009 Iranian presidential election, protests broke out in major cities across Iran in support of opposition candidates Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi. The protests continued until 2010, and were titled the Iranian Green Movement by their proponents, reflecting Mousavi's campaign theme, and Persian Awakening, Persian Spring or Green Revolution.

Neda Agha-Soltan was an Iranian student of philosophy, who was participating in the 2009 presidential election protests with her music teacher, and was walking back to her car when she was fatally shot in the upper chest.

Following the 2009 Iranian presidential election, protests against alleged electoral fraud and in support of opposition candidates Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi occurred in Tehran and other major cities in Iran and around the world starting after the disputed presidential election on 2009 June 12 and continued even after the inauguration of Mahmoud Ahmedinejad as President of Iran on 5 August 2009. This is a timeline of the events which occurred during those protests.

Sohrab Aarabi was a 19-year-old Iranian pro-democracy student whose death became a symbol of protests during 2009 post election unrest in Iran.

Saleh Nikbakht is an Iranian lawyer and academic. He is the spokesman for the Society of Political Prisoners in Iran.

Morteza Najafi pour Moghadam, better known as Shahin Najafi, is an Iranian musician, singer, composer, poet, author, and political activist.

Majid Tavakoli is an Iranian student leader, human rights activist and political prisoner. He used to be a member of the Islamic Students' Association at Tehran's Amirkabir University of Technology, where he studied shipbuilding. He was arrested at least three times by the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence, during the student protests over the disputed Presidential Election of 2009. In response to allegations that he cross-dressed as a disguise to avoid arrest, a campaign protesting his imprisonment featured men posting photos of themselves wearing hijab.

Neda Soltani is an Iranian exile. During the 2009 Iranian election protests, she was teaching English at Azad University when her Facebook profile photo was mistakenly published in many articles about the death of the similarly named Neda Agha-Soltan, who was shot and killed during the protests.

The Embassy of Iran in London is the diplomatic mission of Iran in the United Kingdom. It is located in a terrace overlooking Hyde Park in South Kensington, Westminster, London, next to the embassy of Ethiopia. Iran also maintains a Consular Section at 50 Kensington Court, South Kensington. The embassy building, along with the Ethiopian Embassy and the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum, is one of a group of Grade II listed stucco buildings.

On 16 September 2022, 22-year-old Iranian woman Mahsa Amini, also known as Jina Amini, died in a hospital in Tehran, Iran, under suspicious circumstances. The Guidance Patrol, the religious morality police of Iran's government, arrested Amini for allegedly not wearing the hijab in accordance with government standards. The Law Enforcement Command of the Islamic Republic of Iran stated that she had a heart attack at a police station, collapsed, and fell into a coma before being transferred to a hospital. However, eyewitnesses, including women who were detained with Amini, reported that she was severely beaten and that she died as a result of police brutality, which was denied by the Iranian authorities. The assertions of police brutality, in addition to leaked medical scans, led some observers to believe Amini had a cerebral hemorrhage or stroke due to head injuries received after her arrest.

Civil unrest and protests against the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran associated with the death in police custody of Mahsa Amini began on 16 September 2022 and carried on into 2023, but were said to have "dwindled" or "died down" by spring of 2023. As of September 2023, the "ruling elite" of Iran was said to remain "deeply entrenched" in power. The protests were described as "unlike any the country had seen before", the "biggest challenge" to the government, and "most widespread revolt", since the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

Woman, Life, Freedom is a slogan that originated within the women-led Kurdish movements. This slogan transcended its initial context and garnered global recognition following the 2022 protests in Iran, sparked by the death of Mahsa Amini, who was in custody of Iran’s morality police for “improper” clothing. The phrase rapidly became a universal rallying cry, symbolizing resistance against oppression and the fight for women's rights.

This is a broad timeline of the ongoing series of protests against the government of Iran, sparked by the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini on 16 September 2022. Amini had fallen into a coma after having been detained by the Guidance Patrol, allegedly for wearing an "improper" hijab—in violation of Iran's mandatory hijab law—while visiting Tehran from Saqqez.

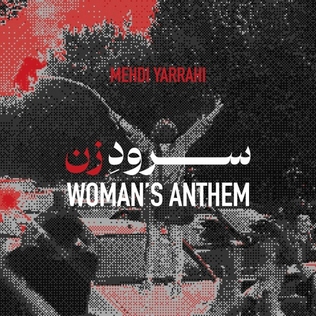

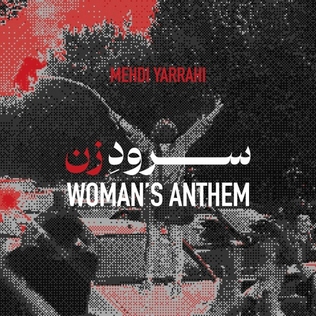

"Soroode Zan" is a song by Iranian singer and composer Mehdi Yarrahi. Composed by Yarrahi and written by Mona Borzouei, it is a protest song with musical composition of anthem style, released eighteen days after the Death of Mahsa Amini —which sparked a massive global protests all around the world— inspired by her death and its aftermath. Beginning with the "Woman, Life, Freedom" slogan, in the lyrics, the narrators are calling everyone to join them in the Mahsa Amini protests.

Aida Rostami was a 36-year-old Iranian physician who was allegedly kidnapped, fatally beaten, and killed by security forces of the Islamic Republic of Iran for treating protesters who were injured during the Mahsa Amini protests. In light of rising demands and threats on Iranian hospitals and medics to assist security forces in the middle of the protests, Aida Rostami has emerged as an inspirational figure among medics associated with the Mahsa Amini protests.

Mahsa Amini, also known as Jina Amini, was an Iranian woman whose arrest in Tehran for opposing mandatory hijab and subsequent death in police custody sparked a wave of protests throughout Iran. People and governments around the world reacted widely to her death. Her death sparked widespread protest in Iranian society, resulting in major protests in various cities in Iran and acts of solidarity around the world. Amini's death ignited the global Woman, Life, Freedom movement - "Woman, Life, Freedom", which demands the end of compulsory hijab laws and other forms of discrimination and oppression against women in Iran. She and the movement were selected as candidates for the Sakharov Prize in 2023 by European Parliament for defending freedom and human rights.