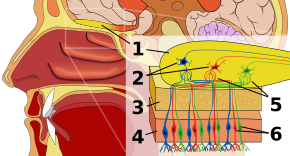

The olfactory nerve, also known as the first cranial nerve, cranial nerve I, or simply CN I, is a cranial nerve that contains sensory nerve fibers relating to the sense of smell.

The olfactory bulb is a neural structure of the vertebrate forebrain involved in olfaction, the sense of smell. It sends olfactory information to be further processed in the amygdala, the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and the hippocampus where it plays a role in emotion, memory and learning.

Stimulus modality, also called sensory modality, is one aspect of a stimulus or what is perceived after a stimulus. For example, the temperature modality is registered after heat or cold stimulate a receptor. Some sensory modalities include: light, sound, temperature, taste, pressure, and smell. The type and location of the sensory receptor activated by the stimulus plays the primary role in coding the sensation. All sensory modalities work together to heighten stimuli sensation when necessary.

The olfactory system, or sense of smell, is the sensory system used for olfaction. Olfaction is one of the special senses directly associated with specific organs. Most mammals and reptiles have a main olfactory system and an accessory olfactory system. The main olfactory system detects airborne substances, while the accessory system senses fluid-phase stimuli.

An aroma compound, also known as an odorant, aroma, fragrance or flavoring, is a chemical compound that has a smell or odor. For an individual chemical or class of chemical compounds to impart a smell or fragrance, it must be sufficiently volatile for transmission via the air to the olfactory system in the upper part of the nose. As examples, various fragrant fruits have diverse aroma compounds, particularly strawberries which are commercially cultivated to have appealing aromas, and contain several hundred aroma compounds.

In medicine and anatomy, the special senses are the senses that have specialized organs devoted to them:

Phantosmia, also called an olfactory hallucination or a phantom odor, is smelling an odor that is not actually there. This is intrinsically suspicious as the formal evaluation and detection of relatively low levels of odour particles is itself a very tricky task in air epistemology. It can occur in one nostril or both. Unpleasant phantosmia, cacosmia, is more common and is often described as smelling something that is burned, foul, spoiled, or rotten. Experiencing occasional phantom smells is normal and usually goes away on its own in time. When hallucinations of this type do not seem to go away or when they keep coming back, it can be very upsetting and can disrupt an individual's quality of life.

In neuroanatomy, topographic map is the ordered projection of a sensory surface or an effector system to one or more structures of the central nervous system. Topographic maps can be found in all sensory systems and in many motor systems.

The Monell Chemical Senses Center is an independent, non-profit scientific research institute located at the University City Science Center campus in Philadelphia. Founded in 1968, it is dedicated to interdisciplinary basic research on the senses of taste and smell. The center's mission is to improve health and well-being by advancing the scientific understanding of taste, smell, and related senses. Monell's research focuses on various aspects of chemosensory science, including how chemical senses affect human health, behavior, and the environment. The center employs a collaborative and interdisciplinary approach, with scientists from diverse fields such as sensory psychology, biophysics, chemistry, behavioral neuroscience, environmental science, and genetics working together on research projects.

Olfactory fatigue, also known as odor fatigue, odor habituation, olfactory adaptation, or noseblindness, is the temporary, normal inability to distinguish a particular odor after a prolonged exposure to that airborne compound. For example, when entering a restaurant initially the odor of food is often perceived as being very strong, but after time the awareness of the odor normally fades to the point where the smell is not perceptible or is much weaker. After leaving the area of high odor, the sensitivity is restored with time. Anosmia is the permanent loss of the sense of smell, and is different from olfactory fatigue.

Rachel Sarah Herz is a Canadian and American psychologist and cognitive neuroscientist, recognized for her research on the psychology of smell.

Dysosmia is a disorder described as any qualitative alteration or distortion of the perception of smell. Qualitative alterations differ from quantitative alterations, which include anosmia and hyposmia. Dysosmia can be classified as either parosmia or phantosmia. Parosmia is a distortion in the perception of an odorant. Odorants smell different from what one remembers. Phantosmia is the perception of an odor when no odorant is present. The cause of dysosmia still remains a theory. It is typically considered a neurological disorder and clinical associations with the disorder have been made. Most cases are described as idiopathic and the main antecedents related to parosmia are URTIs, head trauma, and nasal and paranasal sinus disease. Dysosmia tends to go away on its own but there are options for treatment for patients that want immediate relief.

An odor or odour is a smell or a scent caused by one or more volatilized chemical compounds generally found in low concentrations that humans and many animals can perceive via their olfactory system. While smell can refer to pleasant and unpleasant odors, the terms scent, aroma, and fragrance are usually reserved for pleasant-smelling odors and are frequently used in the food and cosmetic industry to describe floral scents or to refer to perfumes.

The sense of smell, or olfaction, is the special sense through which smells are perceived. The sense of smell has many functions, including detecting desirable foods, hazards, and pheromones, and plays a role in taste.

Olfactory memory refers to the recollection of odors. Studies have found various characteristics of common memories of odor memory including persistence and high resistance to interference. Explicit memory is typically the form focused on in the studies of olfactory memory, though implicit forms of memory certainly supply distinct contributions to the understanding of odors and memories of them. Research has demonstrated that the changes to the olfactory bulb and main olfactory system following birth are extremely important and influential for maternal behavior. Mammalian olfactory cues play an important role in the coordination of the mother infant bond, and the following normal development of the offspring. Maternal breast odors are individually distinctive, and provide a basis for recognition of the mother by her offspring.

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the surroundings through the detection of stimuli. Although, in some cultures, five human senses were traditionally identified as such, many more are now recognized. Senses used by non-human organisms are even greater in variety and number. During sensation, sense organs collect various stimuli for transduction, meaning transformation into a form that can be understood by the brain. Sensation and perception are fundamental to nearly every aspect of an organism's cognition, behavior and thought.

Gordon Murray Shepherd was an American neuroscientist who carried out basic experimental and computational research on how neurons are organized into microcircuits to carry out the functional operations of the nervous system. Using the olfactory system as a model that spans multiple levels of space, time and disciplines, his studies ranged from molecular to behavioral, recognized by an annual lecture at Yale University on "integrative neuroscience". At the time of his death, he was professor of neuroscience emeritus at the Yale School of Medicine. He graduated from Iowa State University with a BA, Harvard Medical School with an MD, and the University of Oxford with a DPhill.

Sniffing is a perceptually-relevant behavior, defined as the active sampling of odors through the nasal cavity for the purpose of information acquisition. This behavior, displayed by all terrestrial vertebrates, is typically identified based upon changes in respiratory frequency and/or amplitude, and is often studied in the context of odor guided behaviors and olfactory perceptual tasks. Sniffing is quantified by measuring intra-nasal pressure or flow or air or, while less accurate, through a strain gauge on the chest to measure total respiratory volume. Strategies for sniffing behavior vary depending upon the animal, with small animals displaying sniffing frequencies ranging from 4 to 12 Hz but larger animals (humans) sniffing at much lower frequencies, usually less than 2 Hz. Subserving sniffing behaviors, evidence for an "olfactomotor" circuit in the brain exists, wherein perception or expectation of an odor can trigger brain respiratory center to allow for the modulation of sniffing frequency and amplitude and thus acquisition of odor information. Sniffing is analogous to other stimulus sampling behaviors, including visual saccades, active touch, and whisker movements in small animals. Atypical sniffing has been reported in cases of neurological disorders, especially those disorders characterized by impaired motor function and olfactory perception.

Retronasal smell, retronasal olfaction, is the ability to perceive flavor dimensions of foods and drinks. Retronasal smell is a sensory modality that produces flavor. It is best described as a combination of traditional smell and taste modalities. Retronasal smell creates flavor from smell molecules in foods or drinks shunting up through the nasal passages as one is chewing. When people use the term "smell", they are usually referring to "orthonasal smell", or the perception of smell molecules that enter directly through the nose and up the nasal passages. Retronasal smell is critical for experiencing the flavor of foods and drinks. Flavor should be contrasted with taste, which refers to five specific dimensions: (1) sweet, (2) salty, (3) bitter, (4) sour, and (5) umami. Perceiving anything beyond these five dimensions, such as distinguishing the flavor of an apple from a pear for example, requires the sense of retronasal smell.

Olfactic communication is a channel of nonverbal communication referring to the various ways people and animals communicate and engage in social interaction through their sense of smell. Our human olfactory sense is one of the most phylogenetically primitive and emotionally intimate of the five senses; the sensation of smell is thought to be the most matured and developed human sense.