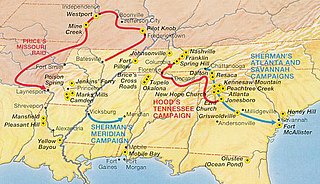

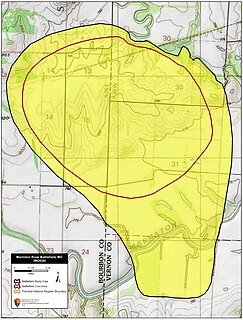

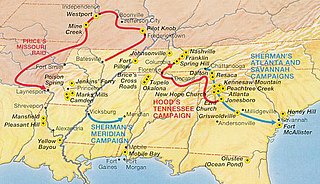

The Battle of Marais des Cygnes took place on October 25, 1864, in Linn County, Kansas, during Price's Missouri Raid in the American Civil War. It is also known as the Battle of Trading Post. In late 1864, Major General Sterling Price invaded the state of Missouri with a cavalry force, attempting to draw Union troops away from the primary theaters of fighting further east. After several victories early in the campaign, Price's Confederate troops were defeated at the Battle of Westport on October 23 near Kansas City, Missouri. The Confederates then withdrew into Kansas, camping along the banks of the Marais des Cygnes River on the night of October 24. Union cavalry pursuers under Brigadier General John B. Sanborn skirmished with Price's rear guard that night, but disengaged without participating in heavy combat.

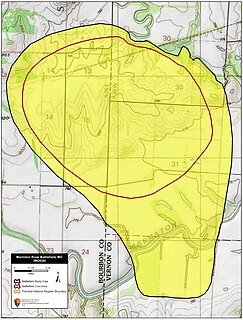

The Battle of Mine Creek, also known as the Battle of the Osage, was fought on October 25, 1864, in Linn County, Kansas as part of Price's Missouri Expedition during the American Civil War. Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate States Army had begun an expedition in September 1864 to restore Confederate control of Missouri. After being defeated at the Battle of Westport near Kansas City, Missouri on October 23, Price's army began to retreat south through Kansas. Early on October 25, Price's army was defeated at the Battle of Marais des Cygnes. After Marais des Cygnes, the Confederates fell back, but were stalled at the crossing of Mine Creek while a wagon train attempted to cross.

The Battle of Westport, sometimes referred to as the "Gettysburg of the West", was fought on October 23, 1864, in modern Kansas City, Missouri, during the American Civil War. Union forces under Major General Samuel R. Curtis decisively defeated an outnumbered Confederate force under Major General Sterling Price. This engagement was the turning point of Price's Missouri Expedition, forcing his army to retreat. The battle ended the last major Confederate offensive west of the Mississippi River, and for the remainder of the war the United States Army maintained solid control over most of Missouri. This battle was one of the largest to be fought west of the Mississippi River, with over 30,000 men engaged.

The Battle of Fort Davidson, also known as the Battle of Pilot Knob, was a battle of Price's Raid fought on September 27, 1864, near Pilot Knob, Missouri. Confederate troops under the command of Major General Sterling Price had entered Missouri in September 1864 with hopes of challenging Union control of the state. On September 24, Price learned that Union troops held Pilot Knob. Two days later, he sent part of his command north to disrupt and then moved towards Pilot Knob with the rest of his army. The Confederate divisions of Major General James F. Fagan and Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke drove Union troops under Brigadier General Thomas Ewing Jr. and Major James Wilson from the lower Arcadia Valley into Fort Davidson on September 26 and on the morning of September 27.

The Battle of Glasgow was fought on October 15, 1864, in and near Glasgow, Missouri as part of Price's Raid during the American Civil War. In late 1864, Confederate leadership in the Trans-Mississippi Theater planned a campaign into the state of Missouri, in hopes of drawing Union troops from more important theaters east of the Mississippi River. Major General Sterling Price commanded the expedition, and initially hoped to capture St. Louis, although an early defeat at the Battle of Pilot Knob led him to abandon this plan. After the strength of the Union garrison at Jefferson City convinced Price to cancel a planned attempt to capture the place, he led his army into the pro-Confederate region of Little Dixie, where recruiting efforts were successful.

The Second Battle of Independence was fought on October 22, 1864, as part of Price's Raid during the American Civil War. In late 1864, Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate States Army led a cavalry force into the state of Missouri in hopes of creating a popular uprising against Union control, draw Union Army troops from more important areas, and affect the 1864 United States Presidential Election. Price was opposed by a combination of Union Army and Kansas State Militia forces positioned near Kansas City and led by Major General Samuel R. Curtis. In addition, Union cavalry under Major General Alfred Pleasonton followed Price from the east. While moving westwards along the Missouri River, Price's men made contact with Union troops at the Little Blue River on October 21. After forcing the Union soldiers to retreat in the Battle of Little Blue River, the Confederates occupied the city of Independence, Missouri.

The Second Battle of Lexington was a minor battle fought during Price's Raid as part of the American Civil War. Hoping to draw Union Army forces away from more important theaters of combat and potentially affect the outcome of the 1864 United States presidential election, Sterling Price, a major general in the Confederate States Army, led an offensive into the state of Missouri on September 19, 1864. After a botched attack at the Battle of Pilot Knob, the strength of the Union defenses at Jefferson City led Price to abandon the main goals of his campaign.

The Battle of Little Blue River was fought on October 21, 1864, as part of Price's Raid during the American Civil War. Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate States Army had led an army into Missouri in September 1864 with hopes of challenging Union control of the state. During the early stages of the campaign, Price abandoned his plan to capture St. Louis and later his secondary target of Jefferson City. The Confederates then began moving westwards, brushing aside Major General James G. Blunt's Union force in the Second Battle of Lexington on October 19. Two days later, Blunt left part of his command under the authority of Colonel Thomas Moonlight to hold the crossing of the Little Blue River, while the rest of his force fell back to Independence. On the morning of October 21, Confederate troops attacked Moonlight's line, and parts of Brigadier General John B. Clark Jr.'s brigade forced its way across the river. A series of attacks and counterattacks ensued, with neither side able to gain a significant advantage.

The Battle of Marmiton River, also known as Shiloh Creek or Charlot's Farm, occurred on October 25, 1864, in Vernon County, Missouri during the American Civil War. Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate States Army commenced an expedition into Missouri in September 1864, with hopes of challenging Union control of the state. After a defeat at the Battle of Westport on October 23, Price began to retreat south, and suffered a serious defeat at the Battle of Mine Creek early on October 25. The afternoon of the 25th, Price's wagon train became stalled at the crossing of the Marmaton River in western Missouri. A delaying force led by Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby attempted to hold off Union cavalry commanded by Brigadier General John McNeil and Lieutenant Colonel Frederick W. Benteen. Shelby was unable to drive off the Union force, although fatigue of the Union cavalry's horses prevented close-quarters action. At nightfall, the Confederates disengaged and destroyed much of their wagon train. Price was again defeated on October 28 at the Second Battle of Newtonia, and the Confederate retreat continued until the survivors reached Texas in early December.

The Battle of Byram's Ford, officially known as the Action at the Big Blue, Mo., was a minor engagement of the American Civil War, comprising two separate skirmishes from October 22 to 23, 1864, in Jackson County, Missouri. It formed a part of the larger Battle of Westport, which ultimately resulted in a Union victory and the end of all major Confederate operations in Missouri.

The First Battle of Newtonia was fought on September 30, 1862, between Confederate soldiers commanded by Colonel Douglas H. Cooper and a Union column commanded by Brigadier General Frederick Salomon near Newtonia, Missouri, during the American Civil War. Cooper's force had moved into southwestern Missouri, and encamped near the town of Newtonia. The Confederate column was composed mostly of cavalry led by Colonel Joseph O. Shelby and a brigade of Native Americans. A Union force commanded by Brigadier General James G. Blunt moved to intercept Cooper's force. Blunt's advance force, led by Salomon, reached the vicinity of Newtonia on September 29, and attacked Cooper's position on September 30. A Union probing force commanded by Colonel Edward Lynde was driven out of Newtonia by Cooper's forces on the morning of the 30th.

The Second Battle of Newtonia was fought on October 28, 1864, near Newtonia, Missouri, between cavalry commanded by Major General James G. Blunt of the Union Army and Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby's rear guard of the Confederate Army of Missouri. In September 1864, Confederate Major General Sterling Price had entered the state of Missouri with hopes of creating a popular uprising against Union control of the state. A defeat at the Battle of Pilot Knob in late September and the strength of Union positions at Jefferson City led Price to abandon the main objectives of the campaign; instead he moved his force west towards Kansas City, where it was badly defeated at the Battle of Westport by Major General Samuel R. Curtis on October 23. Following a set of three defeats on October 25, Price's column halted to rest near Newtonia on October 28.

The 3rd Missouri Cavalry Regiment was a cavalry regiment of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. It was also known as Greene's Regiment after its commander, Colonel Colton Greene.

The 16th Missouri Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. The regiment was formed from men recruited by Jeremiah V. Cockrell and Sidney D. Jackman during an expedition into Missouri in August 1862. Although the recruits fought at the Battle of Lone Jack on August 16, they were not officially mustered into Confederate service until August 31. The regiment fought at the Battle of Prairie Grove on December 7. In May 1863, the regiment was designated the 7th Missouri Infantry Regiment, although this designation was changed to the 16th Missouri Infantry Regiment in December. On July 4, the regiment fought at the Battle of Helena, suffering heavy casualties. The unit then spent time building fortifications at Little Rock, Arkansas, before leaving the town in September. The 16th Missouri then fought at the Battle of Pleasant Hill on April 9, 1864, and at the Battle of Jenkins' Ferry on April 30. On June 8, 1865, the men of the regiment were paroled and sent back to Missouri via steamboat. More men died while serving in the 16th Missouri Infantry Regiment than died in any other Missouri unit serving in the Confederate States Army.

The 12th Missouri Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. After mustering into Confederate service on October 22, 1862, as White's Missouri Infantry, the regiment, as Ponder's Missouri Infantry, fought in the Battle of Prairie Grove on December 7, where it charged the Union lines several times. On May 3, 1863, the regiment was named the 9th Missouri Infantry Regiment, and fought under that name until December 15, 1863, when it was renamed the 12th Missouri Infantry Regiment. On July 4, 1863, the regiment, as part of Brigadier General Mosby M. Parsons' brigade, broke through the Union lines at the Battle of Helena. However, Parsons' flanks were exposed, and the Confederates were driven from the field, suffering heavy losses. After Helena, only 168 men remained in the regiment. On November 22, 1863, the survivors of the regiment were combined into two companies, which were then attached to the 10th Missouri Infantry Regiment, although the 12th Missouri Infantry was still treated as a separate unit for reporting purposes. In April 1864, the 12th Missouri Infantry fought at the battles of Pleasant Hill and Jenkins' Ferry. On September 29, 1864, the survivors of the 12th Missouri Infantry were officially merged into the 10th Missouri Infantry, ending the 12th's separate service career.

Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Regiment was a cavalry regiment of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. Originally formed as Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Battalion, the unit consisted of men recruited in Missouri by Lieutenant Colonel Alonzo W. Slayback during Price's Raid in 1864. The battalion's first action was at the Battle of Pilot Knob on September 27; it later participated in actions at Sedalia, Lexington, and the Little Blue River. In October, the unit was used to find an alternate river crossing during the Battle of the Big Blue River. Later that month, Slayback's unit saw action at the battles of Westport, Marmiton River, and Second Newtonia. The battalion was briefly furloughed in Arkansas before rejoining Major General Sterling Price in Texas in December. Probably around February 1865, the battalion reached official regimental strength after more recruits joined.

The 1st Missouri Field Battery was a field artillery battery that served in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. The battery was formed by Captain Westley F. Roberts in Arkansas in September 1862 as Roberts' Missouri Battery and was originally armed with two 12-pounder James rifles and two 6-pounder smoothbore guns. The unit fought in the Battle of Prairie Grove on December 7, as part of a Confederate offensive. Roberts' Battery withdrew after the battle and transferred to Little Rock, Arkansas, where Roberts resigned and was replaced by Lieutenant Samuel T. Ruffner.

The capture of Sedalia occurred during the American Civil War when a Confederate force attacked the Union garrison of Sedalia, Missouri, on October 15, 1864. In late 1864, with the war having turned against the Confederacy, Major General Sterling Price launched an invasion into the state of Missouri with hopes of distracting the Union from more important areas and causing a popular uprising against Union control of the state. Price had to abandon his goal of capturing St. Louis after a bloody repulse at the Battle of Fort Davidson, and moved into the pro-Confederate region of Little Dixie.

The 13th Missouri Cavalry Regiment was a cavalry regiment that served in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. The unit originated in early April 1863, when Captain Robert C. Wood, aide-de-camp to Confederate Major General Sterling Price, was detached to from an artillery unit from some of the men of Price's escort. Wood continued recruiting for the unit, which was armed with four Williams guns, and had 275 men by the end of September. The next month, the unit participated in the Battle of Pine Bluff, where it drove back Union Army troops into a barricaded defensive position, from which the Union soldiers could not be dislodged. By November, the unit, which was known as Wood's Missouri Cavalry Battalion, had grown to 400 men but no longer had the Williams guns. In April 1864, Wood's battalion, which was also known as the 14th Missouri Cavalry Battalion, played a minor role in the defeat of a Union foraging party in the Battle of Poison Spring. After spending the summer of 1864 at Princeton, Arkansas, Wood's battalion was part of a force Price took into the state of Missouri during Price's Raid. After entering the state in September, the unit made an unsuccessful assault during the Battle of Pilot Knob on September 27.

The 10th Texas Field Battery was an artillery battery that served in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. After being formed in early 1861 by Benjamin H. Pratt, the battery served with a cavalry formation for part of 1862 before operating along the Mississippi River in early 1863. The unit then participated in Marmaduke's Second Expedition into Missouri and the Battle of Pine Bluff in 1863. Late in 1864, the battery, now under the command of H. C. Hynson, served in Price's Raid, participating in several battles and skirmishes, including the disastrous Battle of Mine Creek. The unit's service ended on May 26, 1865.