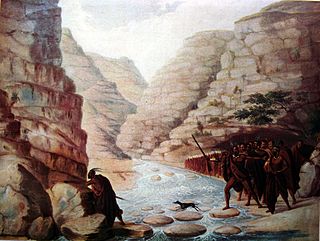

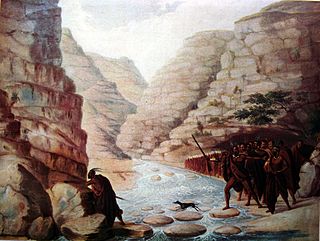

The history of the Cape Colony from 1806 to 1870 spans the period of the history of the Cape Colony during the Cape Frontier Wars, which lasted from 1779 to 1879. The wars were fought between the European colonists and the native Xhosa who, defending their land, fought against European rule.

The amaMfengu were a group of Xhosa clans whose ancestors were refugees that fled from the Mfecane in the early-mid 19th century to seek land and protection from the Xhosa. These refugees were assimilated into the Xhosa nation and were officially recognized by the then king, Hintsa.

Zanemvula Kizito Gatyeni "Zakes" Mda is a South African novelist, poet and playwright. He has won major South African and British literary awards for his novels and plays. He is the son of politician A. P. Mda.

British Kaffraria was a British colony/subordinate administrative entity in present-day South Africa, consisting of the districts now known as Qonce and East London. It was also called Queen Adelaide's Province and, unofficially, British Kaffiria and Kaffirland.

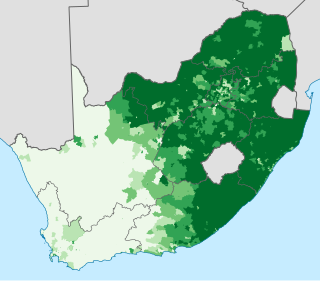

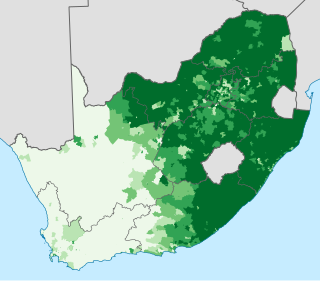

Blacks are the majority ethno-racial group in South Africa, belonging to various Bantu ethnic groups. They are descendants of Southern Bantu-speaking peoples who settled in South Africa during the Bantu expansion.

The Xhosa Wars were a series of nine wars between the Xhosa Kingdom and the British Empire as well as Trekboers in what is now the Eastern Cape in South Africa. These events were the longest-running military resistance against European colonialism in Africa.

King Hintsa ka-Khawuta, also known as King Hintsa Zanzolo , was the king of the Xhosa Kingdom, founded by his ancestor, King Tshawe. He ruled from 1820 until his death in 1835. The kingdom at its peak, during his reign stretched from the Mbhashe River, south of Mthatha, to the Gamtoos River, in the Southern Cape.

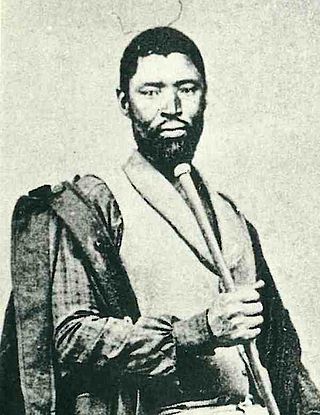

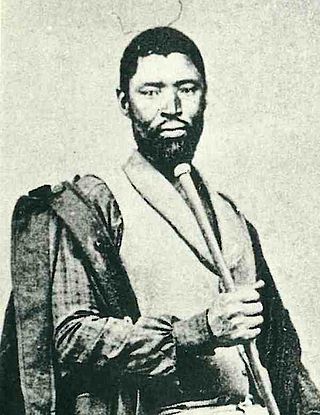

King Sarhili Ka-Hintsa was the King of Xhosa nation from 1835 until his death in 1892 at Sholora, Bomvanaland. He was also known as "Kreli", and led the Xhosa armies in a series of frontier wars.

The Rharhabe House is the second senior house of the Xhosa Kingdom. Its royal palace is in the former Ciskei and its counterpart in the former Transkei is the Gcaleka, which is the great house of Phalo.

The Gcaleka House is the Great house of the Xhosa Kingdom in what is now the Eastern Cape. Its royal palace is in the former Transkei and its counterpart in the former Ciskei is the Rharhabe, which is the right hand house of Phalo.

King Sandile kaNgqika 'Aa! Mgolombane!' was a ruler of the Right Hand House of the Xhosa Kingdom. A dynamic leader, he led the Xhosa armies in several of the Xhosa-British Wars.

Centane, or alternatively anglicised Kentane or Kentani because Europeans often cannot easily pronounce the Xhosa click 'C'; is a settlement in Amathole District Municipality in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is situated at approximately 31 kilometres (19 mi) from Butterworth.

Thembuland, Afrikaans: Temboeland, is a natural region in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. Its territory is the traditional region of the abaThembu.

Jongumsobomvu Maqoma was a Xhosa chief and a commander of the Xhosa forces during the Cape Frontier Wars. Born in the Right Hand House of the Xhosa Kingdom, he was the older brother of Chief Sandile kaNgqika and nephew to King Hintsa. In 1818, he commanded the forces of his father, Ngqika, who seemingly was trying to overthrow the government and become the king of the Xhosa nation. In 1822, he moved to the so-called neutral zone to take land but was expelled by the British troops.

Border is a region of Eastern Cape province in South Africa, comprising roughly the eastern half of the province. Its main centre is East London.

The Imidushane clan was founded by one of the greatest Xhosa warriors Prince Mdushane who was the eldest son of Prince Ndlambe, the son of King Rharhabe.

Nontetha Nkwenkwe was a Xhosa prophetess who lived in colonial South Africa and began a religious movement that caused her to be committed to asylums by the South African government from 1923 until her death in 1935. She is regarded as one of the most remarkable female religious leaders associated with independent churches in the 1920s.

According to their own tradition, the Bomvana originate from the AmaNgwane people of KwaZulu-Natal. The AmaBomvana are descended from Nomafu, the first of the AmaNgwana tribe and from Bomvu, who gave rise to the AmaBomvu tribe. Bomvu's Great Son, Nyonemnyam, carried on the Bomvu dynasty. His son Njilo is the progenitor of the AmaBomvana. The AmaBomvana people left Natal in 1650 to settle in Pondoland after a dispute over cattle. After the death of Njilo’s wife, their grandson Dibandlela refused to send, in accordance with custom, the isizi cattle to his grandfather. This led to an open dispute. Dibandlela fled with his supporters and their cattle to settle in Pondoland

Gobo Fango was a South African who emigrated to the United States with a white Latter-day Saint family in 1861. While he never joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints he was one of the most prominent people of African descent in nineteenth-century Utah. He was murdered in a confrontation with white cowboys in Idaho in 1886.

Jeffrey Brian Peires is a South African historian at the University of Fort Hare. His book about the Xhosa cattle-killing movement of 1856–57, The Dead Will Arise, won the Alan Paton Award in 1990. Peires has also worked as a civil servant in the Eastern Cape and represented the African National Congress in the National Assembly for a brief period from 1994.