Pierre Francis de Marigny Berton, CC, O.Ont. was a Canadian historian, writer, journalist and broadcaster. Berton wrote 50 best-selling books, mainly about Canadiana, Canadian history and popular culture. He also wrote critiques of mainstream religion, anthologies, children's books and historical works for youth. He was a reporter and war correspondent, an editor at Maclean's Magazine and The Toronto Star and, for 39 years, a guest on Front Page Challenge. He was a founder of the Writers' Trust of Canada, and won many honours and awards.

The Klondike Gold Rush was a migration by an estimated 100,000 prospectors to the Klondike region of Yukon in northwestern Canada, between 1896 and 1899. Gold was discovered there by local miners on August 16, 1896; when news reached Seattle and San Francisco the following year, it triggered a stampede of prospectors. Some became wealthy, but the majority went in vain. It has been immortalized in films, literature, and photographs.

Major-general Sir Samuel Benfield Steele was a Canadian soldier and policeman. He was an officer of the North-West Mounted Police, head of the Yukon detachment during the Klondike Gold Rush, and commanding officer of Strathcona's Horse during the Boer War.

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) was a Canadian paramilitary police force, established in 1873, to maintain order in the new Canadian North-West Territories (NWT) following the 1870 transfer of Rupert's Land and North-Western Territory to Canada from the Hudson's Bay Company, the Red River Rebellion and in response to lawlessness, demonstrated by the subsequent Cypress Hills Massacre and fears of United States military intervention. The NWMP combined military, police and judicial functions along similar lines to the Royal Irish Constabulary. A small, mobile police force was chosen to reduce potential for tensions with the United States and First Nations. The NWMP uniforms included red coats deliberately reminiscent of British and Canadian military uniforms.

Dawson City, officially the City of Dawson, is a town in the Canadian territory of Yukon. It is inseparably linked to the Klondike Gold Rush (1896–1899). Its population was 1,577 as of the 2021 census, making it the second-largest municipality in Yukon.

Mount Wood is the seventh-highest mountain in Canada and is located in Kluane National Park and Reserve. In 1900 it was named by the surveyor James J. McArthur (1856–1925) after Zachary Taylor Wood (d.1915), a North-West Mounted Police inspector in Dawson during the Klondike Gold Rush. He was later the commissioner of the NWMP.

Chilkoot Pass is a high mountain pass through the Boundary Ranges of the Coast Mountains in the U.S. state of Alaska and British Columbia, Canada. It is the highest point along the Chilkoot Trail that leads from Dyea, Alaska to Bennett Lake, British Columbia. The Chilkoot Trail was long a route used by the Tlingit for trade.

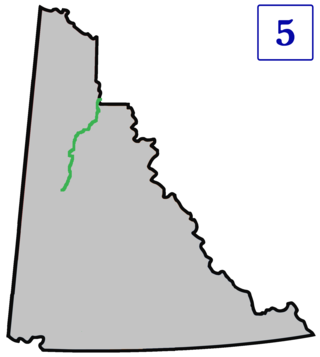

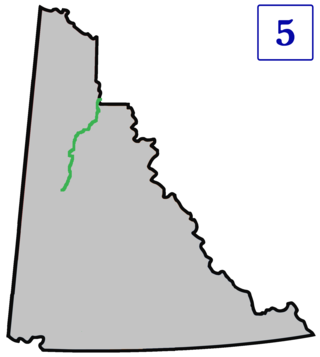

The Dempster Highway, also referred to as Yukon Highway 5 and Northwest Territories Highway 8, is a highway in Canada that connects the Klondike Highway in Yukon to Inuvik, Northwest Territories on the Mackenzie River delta. The highway crosses the Peel and the Mackenzie rivers using a combination of seasonal ferry services and ice bridges. Year-round road access from Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk opened in November 2017, with the completion of the Inuvik–Tuktoyaktuk Highway, creating the first all-weather road route connecting the Canadian road network with the Arctic Ocean.

Charles Constantine was a Canadian North-West Mounted Police officer and superintendent, from Bradford, Yorkshire.

Forty Mile is best known as the oldest town in Canada’s Yukon. It was established in 1886 at the confluence of the Yukon and Fortymile rivers by prospectors and fortune hunters in search of gold. Largely abandoned during the nearby Klondike Gold Rush, the town site continued to be used by Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in. It is currently a historic site that is co-owned and co-managed by Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in and the Government of Yukon. Ch’ëdähdëk became part of the Tr’ondëk-Klondike UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2023, recording of the transformation of the landscape and the Indigenous adaptation to European colonization.

The Northern or Northwestern is a genre in various arts that tell stories set primarily in the late 19th or early 20th century in the north of North America, primarily in western Canada but also in Alaska. It is similar to the Western genre, but many elements are different, as appropriate to its setting. It is common for the central character to be a Mountie instead of a cowboy or sheriff. Other common characters include fur trappers and traders, lumberjacks, prospectors, First Nations people, outlaws, settlers, and townsfolk.

The history of the Yukon covers the period from the arrival of Paleo-Indians through the Beringia land bridge approximately 20,000 years ago. In the 18th century, Russian explorers began to trade with the First Nations people along the Alaskan coast, and later established trade networks extending into Yukon. By the 19th century, traders from the Hudson's Bay Company were also active in the region. The region was administered as a part of the North-Western Territory until 1870, when the United Kingdom transferred the territory to Canada and it became the North-West Territories.

The Yukon Field Force, later termed the Yukon Garrison, was a unit of 203 officers and men from the Permanent Force of the Canadian Militia that served in the Yukon between 1898 and 1900. The force was created in the wake of the Klondike Gold Rush in response to fears that the United States might attempt to seize the region. It left Ottawa on May 6, 1898, travelling by rail and sea to the port of Glenora in British Columbia. From there, the unit made an arduous journey of 890 kilometres (550 mi) on foot and using makeshift boats to Fort Selkirk, where they established their headquarters. A detachment of 72 men was sent to the boom town of Dawson City to support the North-West Mounted Police, with duties that included guarding the gold deposits of the local banks. As the fears of an annexation reduced, pressures grew for the recall of the force. The force was halved in size in July 1898 and the remainder were finally withdrawn in June 1900.

The Klondike Gold Rush is commemorated through film, literature, historical parks etc.

The Grand Forks Hotel was a prominent roadhouse during the Klondike Gold Rush, situated near Dawson City in the Yukon region of Canada.

The O'Brien Brewing and Malting Company, also known as the Klondike Brewery, was a brewery founded by Thomas O'Brien in Klondike City, an adjoining settlement to Dawson City, Yukon Territory, Canada from 1904 to 1919. It was established during a period in which Dawson City was expected to become an important regional city, and used modern techniques and equipment imported from California. It was initially successful, selling 68,748 gallons of beer in 1905, but Dawson's population declined and growing temperance attitudes threatened the business. O'Brien sold the company in 1915, and in 1919 prohibition forced its closure. The brewery was abandoned, and the remains of the site are now owned by the Tr'ondek Hwech'in First Nation.

The Dalton Cache–Pleasant Camp Border Crossing connects the towns of Haines, Alaska and Haines Junction, Yukon on the Canada–United States border. Alaska Route 7 on the American side joins Yukon Highway 3 on the Canadian side as part of the Haines Highway.

Discovery Claim is a mining claim at Bonanza Creek, a watercourse in the Yukon, Canada. It is the site where, in the afternoon of August 16, 1896, the first piece of gold was found in the Yukon by prospectors. The site is considered to be the place where the Klondike gold rush started. It is located around 17 kilometres south-southeast of Dawson City. The Discovery claim was designated a National Historic Site of Canada on July 13, 1998.

American immigration to Canada was a notable part of the social history of Canada. Over Canada's history various refugees and economic migrants from the United States would immigrate to Canada for a variety of reasons. Exiled Loyalists from the United States first came, followed by African-American refugees, economic migrants, and later draft evaders from the Vietnam War.

The Police Trail was built across parts of northern British Columbia as an alternate, overland route to the Yukon gold fields in 1897. It was used by only a few miners during the Yukon gold rush and fell into disrepair, but parts are still used by local hunting guides, hunters, outfitters and trappers.