Major General Sir Samuel Benfield Steele was a Canadian soldier and policeman. He was an officer of the North-West Mounted Police, head of the Yukon detachment during the Klondike Gold Rush, and commanding officer of Strathcona's Horse during the Boer War.

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) was a Canadian paramilitary police force, established in 1873, to maintain order in the new Canadian North-West Territories (NWT) following the 1870 transfer of Rupert's Land and North-Western Territory to Canada from the Hudson's Bay Company, the Red River Rebellion and in response to lawlessness, demonstrated by the subsequent Cypress Hills Massacre and fears of United States military intervention. The NWMP combined military, police and judicial functions along similar lines to the Royal Irish Constabulary. A small, mobile police force was chosen to reduce potential for tensions with the United States and First Nations. The NWMP uniforms included red coats deliberately reminiscent of British and Canadian military uniforms.

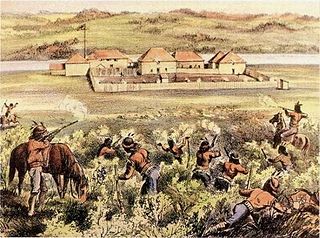

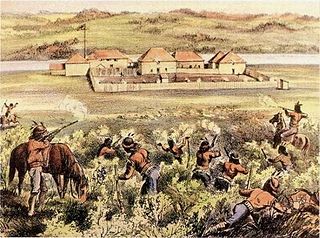

The Cypress Hills Massacre occurred on June 1, 1873, near Battle Creek in the Cypress Hills region of Canada's North-West Territories. It involved a group of American bison hunters, American wolf hunters or "wolfers", American and Canadian whisky traders, Métis cargo haulers or "freighters", and a camp of Assiniboine people. Thirteen or more Assiniboine warriors and one wolfer died in the conflict. The Cypress Hills Massacre prompted the Canadian government to accelerate the recruitment and deployment of the newly formed North-West Mounted Police.

Fort Calgary was a North-West Mounted Police outpost at the confluence of the Bow and Elbow rivers in present-day Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Originally named Fort Brisebois, after the outpost's first commander, the outpost was renamed Fort Calgary in June 1876.

The Battle of Duck Lake was an infantry skirmish 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) outside Duck Lake, Saskatchewan, between North-West Mounted Police forces of the Government of Canada, and the Métis militia of Louis Riel's newly established Provisional Government of Saskatchewan. The skirmish lasted approximately 30 minutes, after which Superintendent Leif Newry Fitzroy Crozier of the NWMP, his forces having endured fierce fire with twelve killed and eleven wounded, called for a general retreat. The battle is considered the initial engagement of the North-West Rebellion. Although Louis Riel proved to be victorious at Duck Lake, the general agreement among historians is that the battle was strategically a disappointment to his cause.

Fort Whoop-Up was the nickname given to a whisky trading post, originally Fort Hamilton, near what is now Lethbridge, Alberta. During the late 19th century, the post served as a centre for trading activities, including the illegal whisky trade. The sale of whisky was outlawed but, due to the lack of law enforcement in the region prior to 1874, many whisky traders had settled in the area and taken to charging unusually high prices for their goods.

Éphrem-A. Brisebois was a Canadian politician, soldier, and police officer with the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) of Canada.

The modern history of Lethbridge extends to the mid-19th century, when the area was developed from drift mines opened by Nicholas Sheran in 1874, and the North Western Coal and Navigation Company in 1882. Prior to the development of drift mines in the area, Lethbridge, Alberta was known as Coal Banks, and was part of the territory of the Blackfoot Confederacy. The Confederacy was made up of the Kainai Nation, the Northern Peigan, the Southern Peigan (Blackfeet), and the Siksika Nation.

Fort Ellice was a Hudson's Bay Company trading post that operated from 1794 to 1892. It was first established in February 1794 by John Sutherland on the Qu'Appelle River about 20 kilometres (12 mi) upstream from its mouth at the Assiniboine River, and known as the Qu'Appelle River Post until it was destroyed by the North West Company in 1816.

Donald Watson Davis was a politician from Northwest Territories, Canada.

Francis Jeffrey Dickens was the third son and fifth child of Victorian English novelist Charles Dickens and his wife Catherine Dickens née Hogarth.

The Red Coat Trail is a 1,300-kilometre (810 mi) route that approximates the path taken in 1874 by the North-West Mounted Police in their March West from Fort Dufferin to Fort Whoop-Up.

Fort Walsh is a National Historic Site of Canada that was a North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) fort and the site of the Cypress Hills Massacre. Administered by Parks Canada, it forms a constituent part of Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park.

The Alberta Provincial Police (APP) was the provincial police service for the province of Alberta, Canada, from 1917 to 1932. The APP was formed as a result of the Royal North-West Mounted Police (RNWMP) leaving the prairie provinces during the First World War due to a lack of sufficient resources in light of its increased responsibilities for national security and reluctance to again enforce Prohibition law recently put into effect by the Alberta government after its experience doing so during territorial times. The RNWMP was replaced by the newly created Alberta Provincial Police on March 1, 1917, which remained responsible for provincial policing until 1932, when it was eliminated as a cost-cutting measure during the Great Depression. The APP was known for its tumultuous beginning, battles against rum-runners and bootleggers during prohibition in Canada and the United States, as well as its remarkable efficiency and professionalism which endeared the force to Albertans.

Philip Carteret Hill Primrose was a Canadian police officer and the fifth Lieutenant Governor of Alberta.

Fort Dufferin is a former Canadian government post near the Canada–United States border at Emerson, Manitoba. The fort was used during the 1870s as a base for the North American Boundary Commission and the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP), and as an immigration station. It was designated a national historic site of Canada in 1937.

The Rocky Mountain Rangers were one of the volunteer militia units raised in Canada's North West in response to the 1885 North-West Rebellion. It was a body of mounted irregulars, mostly cowboys and ranchers from the area around Fort Macleod, the headquarters of the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) at the base of the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, about 150 miles (240 km) west of Medicine Hat. This unit is not to be confused with the present-day Canadian Army Reserve unit The Rocky Mountain Rangers of Kamloops, British Columbia. Rather, it is the ultimate ancestor of the South Alberta Light Horse (SALH).

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) played a significant role during the North-West Rebellion in Canada in 1885. The NWMP suffered early reverses and, although they supported the relief force sent to the region under the command of Major-General Frederick Middleton, their performance was heavily criticized. Commissioner Acheson Irvine resigned from his command of the police as a result.

The history of the North-West Mounted Police in the Canadian north describes the activities of the North-West Mounted Police in the North-West Territories at the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th. The mounted police had been established to control the prairies along the Canadian-United States border in 1873, but were then also deployed to control the Yukon region during the Klondike Gold Rush, and subsequently expanded their operations into the Hudson Bay area and the far north. The force was amalgamated in 1920 to form part of the new Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who continued their predecessors' work across the region.

The Canadian North-West Mounted Police had a prominent role in popular media from the late 19th century onwards. The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP), founded in 1873, were initially viewed with scepticism by the press, but soon became portrayed in media and fictional accounts as courageous, disciplined and chivalrous, displaying a sense of fair-play as they brought their suspects to justice. In the 20th century, over 250 films were made about the force, along with radio and television portrayals.