Nowy Sącz is a city in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship of southern Poland. It is the district capital of Nowy Sącz County as a separate administrative unit. With a population of 83,116 as of 2021, it is the largest city in the Beskid Sądecki Region as well as the third most populous city in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship.

Krynkipronounced[ˈkrɨŋkʲi] is a town in northeastern Poland, located in Podlaskie Voivodeship along the border with Belarus. It lies approximately 24 kilometres (15 mi) south-east of Sokółka and about 45 km (28 mi) east of the regional capital Białystok.

The Kielce cemetery massacre refers to the shooting action by the Nazi German police that took place on May 23, 1943 in occupied Poland during World War II, in which 45 Jewish children who had survived the Kielce Ghetto liquidation, and remained with their working parents at the Kielce forced-labour camps, were rounded up and brought to the Pakosz cemetery in Kielce, Poland, where they were murdered by the German paramilitary police. The children ranged in age from 15 months to 15 years old.

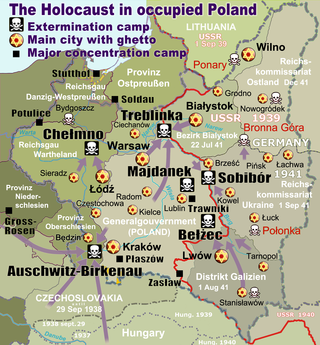

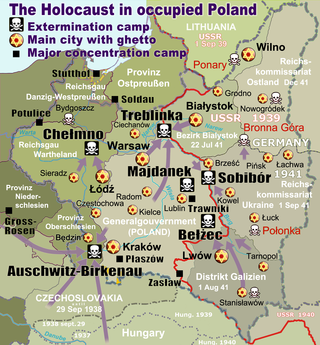

The Białystok Ghetto was a Nazi ghetto set up by the German SS between July 26 and early August 1941 in the newly formed District of Bialystok within occupied Poland. About 50,000 Jews from the vicinity of Białystok and the surrounding region were confined into a small area of the city, which was turned into the district's capital. The ghetto was split in two by the Biała River running through it. Most inmates were put to work in the slave-labor enterprises for the German war effort, primarily in large textile, shoe and chemical companies operating inside and outside its boundaries. The ghetto was liquidated in November 1943. Its inhabitants were transported in Holocaust trains to the Majdanek concentration camp and Treblinka extermination camps. Only a few hundred survived the war, either by hiding in the Polish sector of the city, escape following the Bialystok Ghetto Uprising, or by surviving the camps.

The mass murders in Tykocin occurred on 25 August 1941, during World War II, where the local Jewish population of Tykocin (Poland) was killed by German Einsatzkommando.

Mother Bertranda, O.P., later known as Anna Borkowska, was a Polish cloistered Dominican nun who served as the prioress of her monastery in Kolonia Wileńska near Wilno. She was a graduate of the University of Kraków who had entered the monastery after her studies. During World War II, under her leadership, the nuns of the monastery sheltered 17 young Jewish activists from Vilnius Ghetto and helped the Jewish Partisan Organization (FPO) by smuggling weapons. In recognition of this, in 1984 she was awarded the title of Righteous among the Nations by Yad Vashem.

Polish Jews were the primary victims of the Nazi Germany-organized Holocaust in Poland. Throughout the German occupation of Poland, Jews were rescued from the Holocaust by Polish people, at risk to their lives and the lives of their families. According to Yad Vashem, Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, Poles were, by nationality, the most numerous persons identified as rescuing Jews during the Holocaust. By January 2022, 7,232 people in Poland have been recognized by the State of Israel as Righteous among the Nations.

The Częstochowa Ghetto was a World War II ghetto set up by Nazi Germany for the purpose of persecution and exploitation of local Jews in the city of Częstochowa during the German occupation of Poland. The approximate number of people confined to the ghetto was around 40,000 at the beginning and in late 1942 at its peak, immediately before mass deportations, 48,000. Most ghetto inmates were delivered by the Holocaust trains to Treblinka extermination camp, where they were murdered. In June 1943, the remaining ghetto inhabitants launched the Częstochowa Ghetto uprising, which was extinguished by the SS after a few days of fighting.

The Będzin Ghetto was a World War II ghetto set up by Nazi Germany for the Polish Jews in the town of Będzin in occupied south-western Poland. The formation of the 'Jewish Quarter' was pronounced by the German authorities in July 1940. Over 20,000 local Jews from Będzin, along with additional 10,000 Jews expelled from neighbouring communities, were forced to subsist there until the end of the ghetto history during the Holocaust. Most of the able-bodied poor were forced to work in German military factories before being transported aboard Holocaust trains to the nearby concentration camp at Auschwitz where they were exterminated. The last major deportation of the ghetto inmates by the German SS – men, women and children – between 1 and 3 August 1943 was marked by the ghetto uprising by members of the Jewish Combat Organization.

The Grodno Ghetto was a Nazi ghetto established in November 1941 by Nazi Germany in the city of Grodno for the purpose of persecution and exploitation of Jews in Western Belarus.

The Brześć Ghetto or the Ghetto in Brest on the Bug, also: Brześć nad Bugiem Ghetto, and Brest-Litovsk Ghetto was a Nazi ghetto created in occupied Western Belarus in December 1941, six months after the German troops had invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. Less than a year after the creation of the ghetto, around October 15–18, 1942, most of approximately 20,000 Jewish inhabitants of Brest (Brześć) were murdered; over 5,000 were executed locally at the Brest Fortress on the orders of Karl Eberhard Schöngarth; the rest in the secluded forest of the Bronna Góra extermination site, sent there aboard Holocaust trains under the guise of 'resettlement'.

The Radom Ghetto was a Nazi ghetto set up in March 1941 in the city of Radom during the Nazi occupation of Poland, for the purpose of persecution and exploitation of Polish Jews. It was closed off from the outside officially in April 1941. A year and a half later, the liquidation of the ghetto began in August 1942, and ended in July 1944, with approximately 30,000–32,000 victims deported aboard Holocaust trains to their deaths at the Treblinka extermination camp.

The Sosnowiec Ghetto was a World War II ghetto set up by Nazi German authorities for Polish Jews in the Środula district of Sosnowiec in the Province of Upper Silesia. During the Holocaust in occupied Poland, most inmates, estimated at over 35,000 Jewish men, women and children were deported to Auschwitz death camp aboard Holocaust trains following roundups lasting from June until August 1943. The ghetto was liquidated during an uprising, a final act of defiance of its Underground Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB) made up of youth. Most of the Jewish fighters perished.

Stanisławów Ghetto was a ghetto established in 1941 by Nazi Germany in Stanisławów in German occupied Poland. After the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the town was incorporated into District of Galicia, as the fifth district of the General Government.

The Siedlce Ghetto, was a World War II Jewish ghetto set up by Nazi Germany in the city of Siedlce in occupied Poland, 92 kilometres (57 mi) east of Warsaw. The ghetto was closed from the outside in early October 1941. Some 12,000 Polish Jews were imprisoned there for the purpose of persecution and exploitation. Conditions were appalling; epidemics of typhus and scarlet fever raged. Beginning 22 August 1942 during the most deadly phase of the Holocaust in occupied Poland, around 10,000 Jews were rounded up – men, women and children – gathered at the Umschlagplatz, and deported to Treblinka extermination camp aboard Holocaust trains. Thousands of Jews were brought in from the ghettos in other cities and towns. In total, at least 17,000 Jews were annihilated in the process of ghetto liquidation. Hundreds of Jews were shot on the spot during the house-to-house searches, along with staff and patients of the Jewish hospital.

Zofia Glazer, néeOlszakowska, was a Polish educator and resistance member during World War II, involved in rescue of Jews during the Holocaust.

The Słonim Ghetto was a Nazi ghetto established in 1941 by the SS in Slonim, Western Belarus during World War II. Prior to 1939, the town (Słonim) was part of the Second Polish Republic. The town was captured in late June 1941 by the Wehrmacht in the early stages of Operation Barbarossa. Anti-Jewish measures were promptly put into place, and a barb-wire surrounded ghetto had been created by 12 July. The killings of Jews by mobile extermination squads began almost immediately. Mass killings took place in July and November. The survivors were used as slave labor. After each killing, significant looting by the Nazis occurred. A Judenrat was established to pay a large ransom; after paying out 2 million roubles of gold, its members were then executed. In March 1942, ghettos in the surrounding areas were merged into the Słonim ghetto.

The Kielce Ghetto was a Jewish World War II ghetto created in 1941 by the Schutzstaffel (SS) in the Polish city of Kielce in the south-western region of the Second Polish Republic, occupied by German forces from 4 September 1939. Before the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939, Kielce was the capital of the Kielce Voivodeship. The Germans incorporated the city into Distrikt Radom of the semi-colonial General Government territory. The liquidation of the ghetto took place in August 1942, with over 21,000 victims deported to their deaths at the Treblinka extermination camp, and several thousands more shot, face-to-face.