Related Research Articles

The total number of military and civilian casualties in World War I was about 40 million: estimates range from around 15 to 22 million deaths and about 23 million wounded military personnel, ranking it among the deadliest conflicts in human history.

The Schlieffen Plan is a name given after the First World War to German war plans, due to the influence of Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen and his thinking on an invasion of France and Belgium, which began on 4 August 1914. Schlieffen was Chief of the General Staff of the German Army from 1891 to 1906. In 1905 and 1906, Schlieffen devised an army deployment plan for a decisive (war-winning) offensive against the French Third Republic. German forces were to invade France through the Netherlands and Belgium rather than across the common border.

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff was a German general, politician and military theorist. He achieved fame during World War I for his central role in the German victories at Liège and Tannenberg in 1914. Following his appointment as First Quartermaster-general of the Imperial German Army's Great General Staff in 1916, he became the chief policymaker in a de facto military dictatorship that dominated Germany for the rest of the war. After Germany's defeat, he contributed significantly to the Nazis' rise to power.

The South West Africa campaign was the conquest and occupation of German South West Africa by forces from the Union of South Africa acting on behalf of the British imperial government at the beginning of the First World War.

The First Battle of Ypres was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. The battle was part of the First Battle of Flanders, in which German, French, Belgian armies and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) fought from Arras in France to Nieuwpoort (Nieuport) on the Belgian coast, from 10 October to mid-November. The battles at Ypres began at the end of the Race to the Sea, reciprocal attempts by the German and Franco-British armies to advance past the northern flank of their opponents. North of Ypres, the fighting continued in the Battle of the Yser (16–31 October), between the German 4th Army, the Belgian army and French marines.

The History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Committee of Imperial Defence is a series of 109 volumes, concerning the war effort of the British state during the First World War. It was produced by the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence from 1915 to 1949; after 1919 Brigadier-General Sir James Edmonds was Director. Edmonds wrote many of the army volumes and influenced the choice of historians for the navy, air force, medical and veterinary volumes. Work had begun on the series in 1915 and in 1920, the first volumes of Naval Operations and Seaborne Trade, were published. The first "army" publication, Military Operations: France and Belgium 1914 Part I and a separate map case were published in 1922 and the final volume, The Occupation of Constantinople was published in 2010.

The Hundred Days Offensive was a series of massive Allied offensives that ended the First World War. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens on the Western Front, the Allies pushed the Imperial German Army back, undoing its gains from the German spring offensive.

The Allies, or the Entente Powers, were an international military coalition of countries led by France, the United Kingdom, Russia, the United States, Italy, and Japan against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria in World War I (1914–1918).

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was a British Empire military formation, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914–15), at the beginning of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First World War.

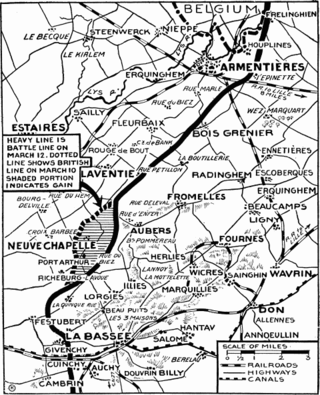

The Battle of Festubert was an attack by the British army in the Artois region of France on the western front during World War I. The offensive formed part of a series of attacks by the French Tenth Army and the British First Army in the Second Battle of Artois (3 May – 18 June 1915). After the failure of the breakthrough attempt by the First Army in the attack at Aubers Ridge tactics of a short hurricane bombardment and an infantry advance with unlimited objectives, were replaced by the French practice of slow and deliberate artillery-fire intended to prepare the way for an infantry attack.

The Serbian campaign was a series of military expeditions launched in 1914 and 1915 by the Central Powers against the Kingdom of Serbia during the First World War.

This list contains a selection of books on World War I, using APA style citations.

This is the history of South Africa from 1910 to 1948.

Gerd Schultze-Rhonhof is a German author and former Generalmajor in the German Army of the Bundeswehr, who, like Udo Walendy, also disputes Germany's sole guilt for the Second World War.

The Fifth Battle of Ypres, also called the Advance in Flanders and the Battle of the Peaks of Flanders is an informal name used to identify a series of World War I battles in northern France and southern Belgium (Flanders) from late September to October 1918.

The Battle of Hartmannswillerkopf was a series of engagements during the First World War fought for the control of the Hartmannswillerkopf peak in Alsace in 1914 and 1915. The peak is a pyramidal rocky spur in the Vosges mountains, about 5 km (3.1 mi) north of Thann, standing at 956 m (3,136 ft) and overlooking the Alsace Plain, Rhine valley and the Black Forest in Germany. Hartmanswillerkopf was captured by the French army during the Battle of Mulhouse (7–10, 14–26 August 1914). From the vantage point, Mulhouse and the Mulhouse–Colmar railway could be seen and the French railway from Thann to Cernay and Belfort shielded from German observation.

14 - Diaries of the Great War is a 2014 international documentary drama series about World War I. It uses a mix of acted scenes, archive footage, and animation. All episodes were directed by Jan Peter, series authors were Jan Peter and Yury Winterberg. In a dramatic advisory capacity, Dutch producer and screenwriter Maarten van der Duin and BBC-author Andrew Bampfield worked on the film's development. The series is based on an idea by Gunnar Dedio, producer at the film company LOOKSfilm and Ulrike Dotzer, the Head of Department ARTE at Norddeutscher Rundfunk.

Gerhard Hirschfeld is a German historian and author. From 1989 to 2011, he was director of the Stuttgart-based Bibliothek für Zeitgeschichte / Library of Contemporary History, and has been a professor at the Institute of History of the University of Stuttgart since 1997. In 2016 he also became a visiting professor at the Institute for International Studies, University of Wuhan/China.

The Bayerisches Armeemuseum is the Military History Museum of Bavaria. It was founded in 1879 in Munich and is located in Ingolstadt since 1972. The main collection is housed in the New Castle, the permanent exhibition about the First World War in Reduit Tilly opened in 1994 and the Armeemuseum incorporated the Bayerisches Polizeimuseum in the Turm Triva in 2012. Today, part of the former Munich Museum building is the central building of the new Bayerische Staatskanzlei.

The war guilt question is the public debate that took place in Germany for the most part during the Weimar Republic, to establish Germany's share of responsibility in the causes of the First World War. Structured in several phases, and largely determined by the impact of the Treaty of Versailles and the attitude of the victorious Allies, this debate also took place in other countries involved in the conflict, such as in the French Third Republic and the United Kingdom.

References

- Davison, Graeme; Hirst, John; MacIntyre, Stuart, eds. (2001) [1998]. The Oxford Companion to Australian History (rev. ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551503-9.

- MacIntyre, Stuart. "Official History". In Davison, Hirst & MacIntyre (2001).

- Hartman, Charles; DeBlasi, Anthony (2012). "The Growth of Historical Method in Tang China". In Foot, Sarah; Robinson, C. F. (eds.). The Oxford History of Historical Writing: 400–1400. Vol. II. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923642-8.

- Wells, N. J. (2011). Official Histories of the Great War 1914–1918. Uckfield: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-906-4.