Related Research Articles

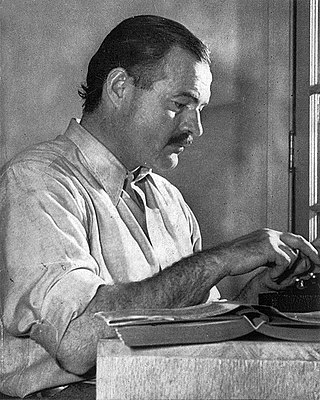

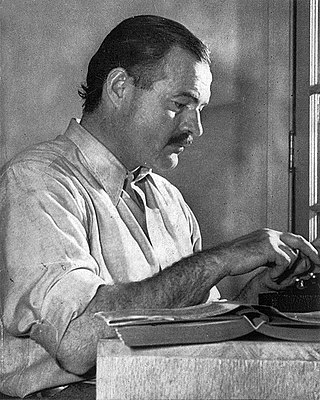

Ernest Miller Hemingway was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Best known for an economical, understated style that significantly influenced later 20th-century writers, he is often romanticized for his adventurous lifestyle, and outspoken and blunt public image. Most of Hemingway's works were published between the mid-1920s and mid-1950s, including seven novels, six short-story collections and two non-fiction works. His writings have become classics of American literature; he was awarded the 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature, while three of his novels, four short-story collections and three nonfiction works were published posthumously.

The Sun Also Rises is the first novel by the American writer Ernest Hemingway. It portrays American and British expatriates who travel along the Camino de Santiago from Paris to the Festival of San Fermín in Pamplona and watch the running of the bulls and the bullfights. An early modernist novel, it received mixed reviews upon publication. Hemingway biographer Jeffrey Meyers writes that it is now "recognized as Hemingway's greatest work" and Hemingway scholar Linda Wagner-Martin calls it his most important novel. The novel was published in the United States in October 1926 by Scribner's. A year later, Jonathan Cape published the novel in London under the title Fiesta. It remains in print.

Donald Barthelme Jr. was an American short story writer and novelist known for his playful, postmodernist style of short fiction. Barthelme also worked as a newspaper reporter for the Houston Post, was managing editor of Location magazine, director of the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston (1961–1962), co-founder of Fiction, and a professor at various universities. He also was one of the original founders of the University of Houston Creative Writing Program.

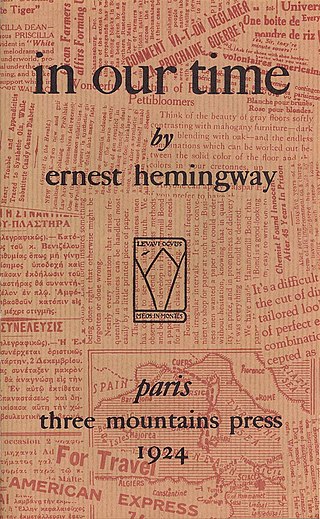

In Our Time is the title of Ernest Hemingway's first collection of short stories, published in 1925 by Boni & Liveright, New York, and of a collection of vignettes published in 1924 in France titled in our time. Its title is derived from the English Book of Common Prayer, "Give peace in our time, O Lord".

True at First Light is a book by American novelist Ernest Hemingway about his 1953–54 East African safari with his fourth wife Mary, released posthumously in his centennial year in 1999. The book received mostly negative or lukewarm reviews from the popular press and sparked a literary controversy regarding how, and whether, an author's work should be reworked and published after his death. Unlike critics in the popular press, Hemingway scholars generally consider True at First Light to be complex and a worthy addition to his canon of later fiction.

Across the River and Into the Trees is a novel by American writer Ernest Hemingway, published by Charles Scribner's Sons in 1950, after first being serialized in Cosmopolitan magazine earlier that year. The title is derived from the last words of U.S. Civil War Confederate General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson: “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.”

The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway: The Finca Vigía Edition, is a posthumous collection of Ernest Hemingway's short fiction, published in 1987. It contains the classic First Forty-Nine Stories as well as 21 other stories and a foreword by his sons.

Nicholas Adams is a fictional character, the protagonist of two dozen short stories and vignettes written in the 1920s and 1930s by American author Ernest Hemingway. Adams is partly inspired by Hemingway's own experiences, from his summers in Northern Michigan at his family cottage to his service in the Red Cross ambulance corps in World War I. The first of Hemingway's stories to feature Nick Adams was published in his 1925 collection In Our Time, with Adams appearing as a young child in "Indian Camp", the collection's first story.

The iceberg theory or theory of omission is a writing technique coined by American writer Ernest Hemingway. As a young journalist, Hemingway had to focus his newspaper reports on immediate events, with very little context or interpretation. When he became a writer of short stories, he retained this minimalistic style, focusing on surface elements without explicitly discussing underlying themes. Hemingway believed the deeper meaning of a story should not be evident on the surface, but should shine through implicitly.

"Big Two-Hearted River" is a two-part short story written by American author Ernest Hemingway, published in the 1925 Boni & Liveright edition of In Our Time, the first American volume of Hemingway's short stories. It features a single protagonist, Hemingway's recurrent autobiographical character Nick Adams, whose speaking voice is heard just three times. The story explores the destructive qualities of war which is countered by the healing and regenerative powers of nature. When it was published, critics praised Hemingway's sparse writing style and it became an important work in his canon.

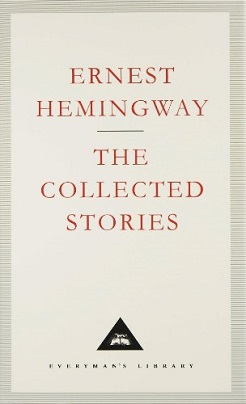

Ernest Hemingway: The Collected Stories is a posthumous collection of Hemingway's short fiction, published in 1995. Introduced by James Fenton, it is published in the UK only by Random House as part of the Everyman Library. The collection is split in two parts.

"Cat in the Rain" is a short story by American author Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), first published by Richard Hadley of Boni & Liveright in 1925 in the short story collection In Our Time. The story is about an American husband and wife on vacation in Italy. Critical attention focuses chiefly on its autobiographical elements and on Hemingway's "theory of omission".

"Fathers and Sons" is a short story by Ernest Hemingway published 1933, in the collection Winner Take Nothing. It later appeared in The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories and The Snows of Kilimanjaro and Other Stories.

"Indian Camp" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway. The story was first published in 1924 in Ford Madox Ford's literary magazine Transatlantic Review in Paris and republished by Boni & Liveright in Hemingway's first American volume of short stories In Our Time in 1925. Hemingway's semi-autobiographical character Nick Adams—a child in this story—makes his first appearance in "Indian Camp", told from his point of view.

"The End of Something" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway, published in the 1925 New York edition of In Our Time, by Boni & Liveright. The story is the third in the collection to feature Nick Adams, Hemingway's autobiographical alter ego.

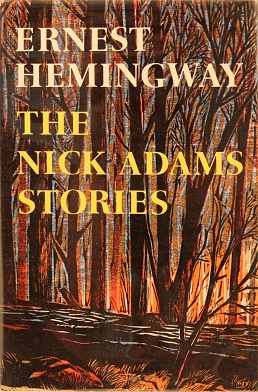

The Nick Adams Stories is a volume of short stories written by Ernest Hemingway published in 1972, a decade after the author's death. In the volume, all the stories featuring Nick Adams, published in various collections during Hemingway's lifetime, are compiled in a single collection. The Nick Adams Stories includes 24 stories and sketches, eight of which were previously unpublished. Some of Hemingway's earliest work, such as "Indian Camp," as well as some of his best known stories, such as "Big Two-Hearted River," are represented.

"The Doctor and the Doctor's Wife" is a short story by Ernest Hemingway, published in the 1925 New York edition of In Our Time, by Boni & Liveright. The story is the second in the collection to feature Nick Adams, Hemingway's autobiographical alter ego. "The Doctor and the Doctor's Wife" follows "Indian Camp" in the collection, includes elements of the same style and themes, yet is written in counterpoint to the first story.

"Cross Country Snow" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway. The story was first published in 1924 in Ford Madox Ford's literary magazine Transatlantic Review in Paris and republished by Boni & Liveright in Hemingway's first American volume of short stories In Our Time in 1925. The story features Hemingway's recurrent autobiographical character Nick Adams and explores the regenerative powers of nature and the joy of skiing.

"My Old Man" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway, published in his 1923 book Three Stories and Ten Poems, which published by a small Paris imprint. The story was also included in his next collection of stories, In Our Time, published in New York in 1925 by Boni & Liveright. The story tells of a boy named Joe whose father is a steeplechase jockey, and is narrated from Joe's point-of-view.

"Out of Season" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway, first published in 1923 in Paris in the privately printed book, Three Stories and Ten Poems. It was included in his next collection of stories, In Our Time, published in New York in 1925 by Boni & Liveright. Set in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy, the story is about an expatriate American husband and wife who spend the day fishing, with a local guide. Critical attention focuses chiefly on its autobiographical elements and on Hemingway's claim that it was his first attempt at using the "theory of omission".

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hemingway, Ernest. “On Writing.” The Nick Adams Stories. Scribner, 1972, pages 233-241.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Flora, Joseph M. “Saving Nick Adams for Another Day.” South Atlantic Review, Vol. 58, No. 2 (May 1993), pages 61-84.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Moddelmog, Debra A. “The Unifying Consciousness of a Divided Conscience: Nick Adams as Author of In Our Time.” American Literature, Vol. 60, No. 4 (Dec. 1988), pages 591-610.

- 1 2 Vaughn, Elizabeth Dewberry. “In Our Time as Self-Begetting Fiction.” Hemingway: Seven Decades of Criticism. Linda Wagner-Martin, ed. Michigan State University Press, 1998, pages 135-147.

- 1 2 3 4 Broer, Lawrence. “Hemingway’s ‘On Writing’: A Portrait of the Artist as Nick Adams.” Bloom’s Major Literary Characters: Nick Adams. Harold Bloom, ed. Chelsea House Publishers, 2004, pages 87-96.

- ↑ Smith, Paul. “Who Wrote Hemingway’s In Our Time?” Bloom’s Major Literary Characters: Nick Adams. Harold Bloom, ed. Chelsea House Publishers, 2004, pages 105-112.

- ↑ Renza, Louis A. “The Importance of Being Ernest.” Hemingway: Seven Decades of Criticism. Linda Wagner-Martin, ed. Michigan State University Press, 1998, pages 213-238.