Related Research Articles

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA. The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as regulatory sequences, and often a substantial fraction of junk DNA with no evident function. Almost all eukaryotes have mitochondria and a small mitochondrial genome. Algae and plants also contain chloroplasts with a chloroplast genome.

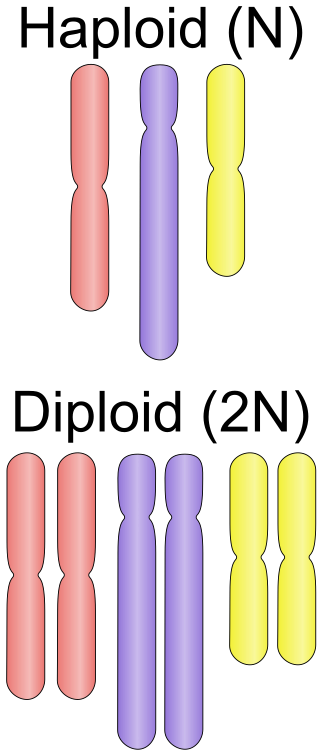

Ploidy is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Here sets of chromosomes refers to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively, in each homologous chromosome pair—the form in which chromosomes naturally exist. Somatic cells, tissues, and individual organisms can be described according to the number of sets of chromosomes present : monoploid, diploid, triploid, tetraploid, pentaploid, hexaploid, heptaploid or septaploid, etc. The generic term polyploid is often used to describe cells with three or more sets of chromosomes.

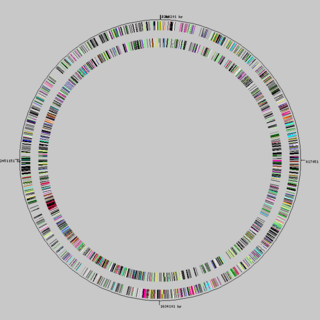

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as the DNA within each of the 24 distinct chromosomes in the cell nucleus. A small DNA molecule is found within individual mitochondria. These are usually treated separately as the nuclear genome and the mitochondrial genome. Human genomes include both protein-coding DNA sequences and various types of DNA that does not encode proteins. The latter is a diverse category that includes DNA coding for non-translated RNA, such as that for ribosomal RNA, transfer RNA, ribozymes, small nuclear RNAs, and several types of regulatory RNAs. It also includes promoters and their associated gene-regulatory elements, DNA playing structural and replicatory roles, such as scaffolding regions, telomeres, centromeres, and origins of replication, plus large numbers of transposable elements, inserted viral DNA, non-functional pseudogenes and simple, highly repetitive sequences. Introns make up a large percentage of non-coding DNA. Some of this non-coding DNA is non-functional junk DNA, such as pseudogenes, but there is no firm consensus on the total amount of junk DNA.

Non-coding DNA (ncDNA) sequences are components of an organism's DNA that do not encode protein sequences. Some non-coding DNA is transcribed into functional non-coding RNA molecules. Other functional regions of the non-coding DNA fraction include regulatory sequences that control gene expression; scaffold attachment regions; origins of DNA replication; centromeres; and telomeres. Some non-coding regions appear to be mostly nonfunctional, such as introns, pseudogenes, intergenic DNA, and fragments of transposons and viruses. Regions that are completely nonfunctional are called junk DNA.

Junk DNA is a DNA sequence that has no known biological function. Most organisms have some junk DNA in their genomes—mostly, pseudogenes and fragments of transposons and viruses—but it is possible that some organisms have substantial amounts of junk DNA.

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than two paired sets of (homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two complete sets of chromosomes, one from each of two parents; each set contains the same number of chromosomes, and the chromosomes are joined in pairs of homologous chromosomes. However, some organisms are polyploid. Polyploidy is especially common in plants. Most eukaryotes have diploid somatic cells, but produce haploid gametes by meiosis. A monoploid has only one set of chromosomes, and the term is usually only applied to cells or organisms that are normally diploid. Males of bees and other Hymenoptera, for example, are monoploid. Unlike animals, plants and multicellular algae have life cycles with two alternating multicellular generations. The gametophyte generation is haploid, and produces gametes by mitosis; the sporophyte generation is diploid and produces spores by meiosis.

A karyotype is the general appearance of the complete set of chromosomes in the cells of a species or in an individual organism, mainly including their sizes, numbers, and shapes. Karyotyping is the process by which a karyotype is discerned by determining the chromosome complement of an individual, including the number of chromosomes and any abnormalities.

Molecular evolution describes how inherited DNA and/or RNA change over evolutionary time, and the consequences of this for proteins and other components of cells and organisms. Molecular evolution is the basis of phylogenetic approaches to describing the tree of life. Molecular evolution overlaps with population genetics, especially on shorter timescales. Topics in molecular evolution include the origins of new genes, the genetic nature of complex traits, the genetic basis of adaptation and speciation, the evolution of development, and patterns and processes underlying genomic changes during evolution.

Gene duplication is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene. Gene duplications can arise as products of several types of errors in DNA replication and repair machinery as well as through fortuitous capture by selfish genetic elements. Common sources of gene duplications include ectopic recombination, retrotransposition event, aneuploidy, polyploidy, and replication slippage.

Evolution of sexual reproduction describes how sexually reproducing animals, plants, fungi and protists could have evolved from a common ancestor that was a single-celled eukaryotic species. Sexual reproduction is widespread in eukaryotes, though a few eukaryotic species have secondarily lost the ability to reproduce sexually, such as Bdelloidea, and some plants and animals routinely reproduce asexually without entirely having lost sex. The evolution of sexual reproduction contains two related yet distinct themes: its origin and its maintenance. Bacteria and Archaea (prokaryotes) have processes that can transfer DNA from one cell to another, but it is unclear if these processes are evolutionarily related to sexual reproduction in Eukaryotes. In eukaryotes, true sexual reproduction by meiosis and cell fusion is thought to have arisen in the last eukaryotic common ancestor, possibly via several processes of varying success, and then to have persisted.

Functional genomics is a field of molecular biology that attempts to describe gene functions and interactions. Functional genomics make use of the vast data generated by genomic and transcriptomic projects. Functional genomics focuses on the dynamic aspects such as gene transcription, translation, regulation of gene expression and protein–protein interactions, as opposed to the static aspects of the genomic information such as DNA sequence or structures. A key characteristic of functional genomics studies is their genome-wide approach to these questions, generally involving high-throughput methods rather than a more traditional "candidate-gene" approach.

The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) is a public research project which aims "to build a comprehensive parts list of functional elements in the human genome."

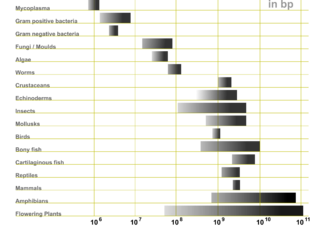

C-value is the amount, in picograms, of DNA contained within a haploid nucleus or one half the amount in a diploid somatic cell of a eukaryotic organism. In some cases, the terms C-value and genome size are used interchangeably; however, in polyploids the C-value may represent two or more genomes contained within the same nucleus. Greilhuber et al. have suggested some new layers of terminology and associated abbreviations to clarify this issue, but these somewhat complex additions are yet to be used by other authors.

Genome size is the total amount of DNA contained within one copy of a single complete genome. It is typically measured in terms of mass in picograms or less frequently in daltons, or as the total number of nucleotide base pairs, usually in megabases. One picogram is equal to 978 megabases. In diploid organisms, genome size is often used interchangeably with the term C-value.

Paleopolyploidy is the result of genome duplications which occurred at least several million years ago (MYA). Such an event could either double the genome of a single species (autopolyploidy) or combine those of two species (allopolyploidy). Because of functional redundancy, genes are rapidly silenced or lost from the duplicated genomes. Most paleopolyploids, through evolutionary time, have lost their polyploid status through a process called diploidization, and are currently considered diploids, e.g., baker's yeast, Arabidopsis thaliana, and perhaps humans.

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protein-coding genes and non-coding genes.

Neutral mutations are changes in DNA sequence that are neither beneficial nor detrimental to the ability of an organism to survive and reproduce. In population genetics, mutations in which natural selection does not affect the spread of the mutation in a species are termed neutral mutations. Neutral mutations that are inheritable and not linked to any genes under selection will be lost or will replace all other alleles of the gene. That loss or fixation of the gene proceeds based on random sampling known as genetic drift. A neutral mutation that is in linkage disequilibrium with other alleles that are under selection may proceed to loss or fixation via genetic hitchhiking and/or background selection.

Genome evolution is the process by which a genome changes in structure (sequence) or size over time. The study of genome evolution involves multiple fields such as structural analysis of the genome, the study of genomic parasites, gene and ancient genome duplications, polyploidy, and comparative genomics. Genome evolution is a constantly changing and evolving field due to the steadily growing number of sequenced genomes, both prokaryotic and eukaryotic, available to the scientific community and the public at large.

Allium is a genus of monocotyledonous flowering plants with hundreds of species, including the cultivated onion, garlic, scallion, shallot, leek, and chives. It is one of about 57 genera of flowering plants with more than 500 species. It is by far the largest genus in the Amaryllidaceae, and also in the Alliaceae in classification systems in which that family is recognized as separate.

The G-value paradox arises from the lack of correlation between the number of protein-coding genes among eukaryotes and their relative biological complexity. The microscopic nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, for example, is composed of only a thousand cells but has about the same number of genes as a human. Researchers suggest resolution of the paradox may lie in mechanisms such as alternative splicing and complex gene regulation that make the genes of humans and other complex eukaryotes relatively more productive.

References

- ↑ Palazzo, Alexander F.; Gregory, T. Ryan (8 May 2014). Akey, Joshua M. (ed.). "The Case for Junk DNA". PLOS Genetics. 10 (5): e1004351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004351 . ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 4014423 . PMID 24809441.

In summary, the notion that the majority of eukaryotic noncoding DNA is functional is very difficult to reconcile with the massive diversity in genome size observed among species, including among some closely related taxa. The onion test is merely a restatement of this issue, which has been well known to genome biologists for many decades.

- 1 2 "The onion test. « Genomicron". www.genomicron.evolverzone.com. 25 April 2007. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ↑ Moran, Laurence A. (12 October 2011). "Sandwalk: A Twofer". Sandwalk. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (8 March 2015). "Is most of our DNA garbage?". The New York Times Magazine.

- ↑ Palazzo, Alexander F.; Gregory, T. Ryan (8 May 2014). Akey, Joshua M. (ed.). "The Case for Junk DNA". PLOS Genetics. 10 (5): e1004351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004351 . ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 4014423 . PMID 24809441.

- ↑ Freeling, Michael; Xu, Jie; Woodhouse, Margaret; Lisch, Damon (2015). "A Solution to the C-Value Paradox and the Function of Junk DNA: The Genome Balance Hypothesis". Molecular Plant. 8 (6): 899–910. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.02.009 . PMID 25743198.

- ↑ Germain, Pierre-Luc; Ratti, Emanuele; Boem, Federico (2014). "Junk or functional DNA? ENCODE and the function controversy". Biology & Philosophy. 29 (6): 807–831. doi:10.1007/s10539-014-9441-3. ISSN 0169-3867. S2CID 84480632.

- ↑ Graur, D.; Zheng, Y.; Price, N.; Azevedo, R. B. R.; Zufall, R. A.; Elhaik, E. (26 March 2013). "On the Immortality of Television Sets: "Function" in the Human Genome According to the Evolution-Free Gospel of ENCODE". Genome Biology and Evolution. 5 (3): 578–590. doi:10.1093/gbe/evt028. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 3622293 . PMID 23431001.

- ↑ Graur, Dan (2016). Molecular and genome evolution. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781605354699. OCLC 951474209.

- 1 2 Ricroch, A; Yockteng, R; Brown, S C; Nadot, S (2005). "Evolution of genome size across some cultivated Allium species". Genome. 48 (3): 511–520. doi:10.1139/g05-017. ISSN 0831-2796. PMID 16121247.

- 1 2 "Why the "Onion Test" Fails as an Argument for "Junk DNA"". Evolution News. 2 November 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ↑ Moran, Laurence A. (12 October 2011). "Sandwalk: A Twofer". Sandwalk.

- ↑ Moran, Larry (2 November 2011). "Sandwalk: Jonathan M Flunks the Onion Test, Again". Sandwalk. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ↑ @ewanbirney (5 September 2012). "Register" (Tweet). Retrieved 20 July 2020– via Twitter.

- ↑ @leonidkruglyak (5 September 2012). "Register" (Tweet). Retrieved 20 July 2020– via Twitter.

- ↑ Mattick, John S.; Dinger, Marcel E. (15 July 2013). "The extent of functionality in the human genome". The HUGO Journal. 7 (1): 2. doi: 10.1186/1877-6566-7-2 . ISSN 1877-6566. PMC 4685169 .

- ↑ Freeling, Michael; Xu, Jie; Woodhouse, Margaret; Lisch, Damon (1 June 2015). "A Solution to the C-Value Paradox and the Function of Junk DNA: The Genome Balance Hypothesis". Molecular Plant. 8 (6): 899–910. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.02.009 . PMID 25743198.