The September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center elicited a large response of local emergency and rescue personnel to assist in the evacuation of the two towers, resulting in a large loss of the same personnel when the towers collapsed. After the attacks, the media termed the World Trade Center site "Ground Zero", while rescue personnel referred to it as "the Pile".

Communication problems and successes played an important role during the September 11 attacks in 2001 and their aftermath. Systems were variously destroyed or overwhelmed by loads greater than they were designed to carry, or failed to operate as intended or desired.

The September 11 attacks of 2001, in addition to being a unique act of terrorism, constituted a media event on a scale not seen since the advent of civilian global satellite links. Instant worldwide reaction and debate were made possible by round-the-clock television news organizations and by the internet. As a result, most of the events listed below were known by a large portion of the world's population as they occurred.

9/11 is a 2002 documentary film about the September 11 attacks in New York City, in which two planes were flown into the buildings of the World Trade Center, resulting in their destruction and the deaths of nearly 3,000 people. The film is from the point of view of the New York City Fire Department. The film was directed by brothers Jules and Gédéon Naudet and FDNY firefighter James Hanlon and produced by Susan Zirinsky of CBS News.

The New York City Fire Department, officially the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY) is the full-service fire department of New York City, serving all five boroughs. The FDNY is responsible for providing Fire Suppression Services, Specialized Hazardous Materials Response Services, Emergency Medical Response Services and Specialized Technical Rescue Services in the entire city.

Ronald Paul Bucca was a New York City Fire Department Marshal killed during the September 11 attacks during the collapse of the World Trade Center. He was the only fire marshal in the history of the New York City Fire Department to be killed in the line of duty.

Jules Clément Naudet and brother Thomas Gédéon Naudet are French-American filmmakers. The brothers, residents of the United States since 1989 and citizens since 1999, were in New York City at the time of the September 11 attacks to film a documentary on members of the Engine 7, Ladder 1 firehouse in Lower Manhattan.

Peter James Ganci Jr. was a career firefighter in the New York City Fire Department killed in the September 11 attacks. At the time of the attacks, he held the rank of Chief of Department, the highest ranking uniformed fire officer in the department.

Thomas Von Essen was appointed the 30th FDNY Commissioner of the City of New York by Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani on April 15, 1996, and served in that position until the end of the Giuliani Administration on December 31, 2001, nearly four months after the September 11, 2001 attacks.

William Michael Feehan was a member of the Fire Department of New York who died during the collapse of the World Trade Center during the September 11 attacks. He was the second-highest official in the department.

"The Real Rudy" is a series of four viral videos by documentary film director and activist Robert Greenwald.

Rudy Giuliani: Urban Legend is a video produced by the International Association of Firefighters (IAFF). On July 11, 2007, the IAFF released the 13-minute video in DVD format to fire departments across the U.S. The DVD outlines its complaints against Rudy Giuliani. It is critical of the 2008 Republican Party presidential candidate and former New York City mayor. As the video has been issued on a website, and not just DVD, it is classifiable as a viral video.

The 23rd Street Fire was an incident that took place in the Flatiron District neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, on October 17, 1966. A group of firefighters from the New York City Fire Department responding to a fire at 7 East 22nd Street entered a building at 6 East 23rd Street as part of an effort to fight the fire. Twelve firefighters were killed after the floor collapsed, the largest loss of life in the department's history until the collapse of the World Trade Center in the September 11 attacks of 2001.

Welles Remy Crowther was an American equities trader and volunteer firefighter known for saving as many as 18 lives during the September 11 attacks in New York City, during which he lost his own life.

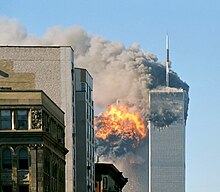

The September 11 attacks were the deadliest terrorist attacks in human history, causing the deaths of 2,996 people, including 2,977 victims and 19 hijackers who committed murder–suicide. Thousands more were injured, and long-term health effects have arisen as a consequence of the attacks. New York City took the brunt of the death toll when the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center complex in Lower Manhattan were attacked, with an estimated 1,600 victims from the North Tower and around a thousand from the South Tower. Two hundred miles southwest in Arlington County, Virginia, another 125 were killed in the Pentagon. The remaining 265 fatalities included the ninety-two passengers and crew of American Airlines Flight 11, the sixty-five aboard United Airlines Flight 175, the sixty-four on American Airlines Flight 77 and the forty-four who boarded United Airlines Flight 93. The attack on the World Trade Center's North Tower alone made the September 11 attacks the deadliest act of terrorism in human history.

Vincent Joseph Dunn is a retired firefighter who served the New York Fire Department for 42 years, rising in rank to Commander of Division 3. A longtime contributing editor to Firehouse Magazine, he is the author of nine books on firefighting and one memoir. He published two of his books before his 1999 retirement from New York City Fire Department: "Collapse of Burning Buildings: A Guide to Fireground Safety," 1988; and "Safety and Survival on the Fireground," 1992. His later books are "Command and Control of Fires and Emergencies," 2000; "Strategy of Firefighting," 2007; "Building Construction the Firefighters Battlespace," 2018; "Fire the Battlespace Enemy," 2020; Battlespace Combat," 2020; "Skyscraper Battlespace High-Rise Firefighting," published 2022, and “Battlespace Life-or-Death Decisions,” published 2023. All of Chief Dunn's books are available at vincentdunn.com.

New York City Fire Department Ladder Company 3, also known as Ladder 3, is a fire company and one of two ladder companies in the New York City Fire Department's (FDNY) 6th Battalion, 1st Division. It is housed at 108 E. 13th St., along with Battalion Chief 6, and has firefighting stewardship over a several square block area of Manhattan’s East Village. The company was created on September 11, 1865, and is one of New York’s oldest ladder companies.

Melissa Cándida Doi was an American senior manager at IQ Financial Systems, who died in the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center.

The 1989 New York City Marathon was the 20th running of the annual marathon race in New York City, United States, which took place on Sunday, November 5. The men's elite race was won by Tanzania's Juma Ikangaa in a time of 2:08:01 hours while the women's race was won by Norway's Ingrid Kristiansen in 2:25:30.

Joseph W. Pfeifer is a retired American firefighter who served with the New York City Fire Department (FDNY). Pfeifer served as First Deputy Commissioner of the FDNY from February 2023 until September 2024, and as Acting Fire Commissioner of the FDNY in August 2024. Prior to his civilian work in the FDNY, Pfeifer was an Assistant Chief. He retired in 2018.