Related Research Articles

Apollo is one of the Olympian deities in ancient Greek and Roman religion and Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, music and dance, truth and prophecy, healing and diseases, the Sun and light, poetry, and more. One of the most important and complex of the Greek gods, he is the son of Zeus and Leto, and the twin brother of Artemis, goddess of the hunt. He is considered to be the most beautiful god and is represented as the ideal of the kouros. Apollo is known in Greek-influenced Etruscan mythology as Apulu.

The Dorians were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Hellenes of Classical Greece divided themselves. They are almost always referred to as just "the Dorians", as they are called in the earliest literary mention of them in the Odyssey, where they already can be found inhabiting the island of Crete.

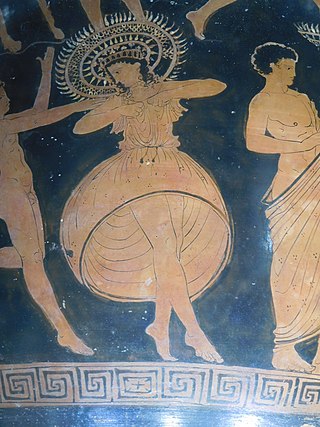

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Helios is the god who personifies the Sun. His name is also Latinized as Helius, and he is often given the epithets Hyperion and Phaethon. Helios is often depicted in art with a radiant crown and driving a horse-drawn chariot through the sky. He was a guardian of oaths and also the god of sight. Though Helios was a relatively minor deity in Classical Greece, his worship grew more prominent in late antiquity thanks to his identification with several major solar divinities of the Roman period, particularly Apollo and Sol. The Roman Emperor Julian made Helios the central divinity of his short-lived revival of traditional Roman religious practices in the 4th century AD.

Asclepius is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Greek religion and mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis, or Arsinoe, or of Apollo alone. Asclepius represents the healing aspect of the medical arts; his daughters, the "Asclepiades", are: Hygieia, Iaso, Aceso, Aegle and Panacea. He has several sons as well. He was associated with the Roman/Etruscan god Vediovis and the Egyptian Imhotep. He shared with Apollo the epithet Paean. The rod of Asclepius, a snake-entwined staff similar to the caduceus, remains a symbol of medicine today. Those physicians and attendants who served this god were known as the Therapeutae of Asclepius.

In ancient Greek religion, Telesphorus was a minor child-god of healing. He was a possible son of Asclepius and frequently accompanied his sister Hygieia. He was depicted as a dwarf whose head was always covered with a cowl hood or cap.

Eshmun was a Phoenician god of healing and the tutelary god of Sidon.

Hero cults were one of the most distinctive features of ancient Greek religion. In Homeric Greek, "hero" refers to the mortal offspring of a human and a god. By the historical period, however, the word came to mean specifically a dead man, venerated and propitiated at his tomb or at a designated shrine, because his fame during life or his unusual manner of death gave him power to support and protect the living. A hero was more than human but less than a god, and various kinds of minor supernatural figures came to be assimilated to the class of heroes; the distinction between a hero and a god was less than certain, especially in the case of Heracles, the most prominent, but atypical hero.

Mesomedes of Crete was a Greek citharode and lyric poet and composer of the early 2nd century AD in Roman Greece. Prior to the discovery of the Seikilos epitaph in the late 19th century, the hymns of Mesomedes were the only surviving written music from the ancient world. Three were published by Vincenzo Galilei in his Dialogo della musica antica e della moderna, during a period of intense investigation into music of the ancient Greeks. These hymns had been preserved through the Byzantine tradition(Anthol. pal. xiv. 63, xvi. 323), and were presented to Vincenzo by Girolamo Mei.

The Delphic Hymns are two musical compositions from Ancient Greece, which survive in substantial fragments. They were long regarded as being dated c. 138 BC and 128 BC, respectively, but recent scholarship has shown it likely they were both written for performance at the Athenian Pythaids in 128 BC. If indeed it dates from ten years before the second, the First Delphic Hymn is the earliest unambiguous surviving example of notated music from anywhere in the Western world whose composer is known by name. Inscriptions indicate that the First Delphic Hymn was written by Athenaeus, son of Athenaeus, while Limenius is credited as the Second Delphic Hymn's composer.

Limenius was an Athenian musician and the creator of the Second Delphic Hymn in 128 BC. He is the earliest known composer in recorded history for a surviving piece of music, or one of the two earliest, or the second-earliest, depending first on whether one accepts the proposition of Bélis that the composer of the First Delphic Hymn is named Athenaeus and, second, whether that hymn was composed in the same year as the Second Hymn, or ten years earlier. Limenius was a performer on the kithara and, as a professional musician performing in the Pythaïs, he was required to belong to one of the guilds of the Artists of Dionysus.

Carneia or Carnea (Κάρνεα) was one of the tribal traditional festivals of Sparta, the Peloponnese and Doric cities in Magna Grecia, held in honor of Apollo Karneios. Whether Carneus was originally an old Peloponnesian divinity subsequently identified with Apollo, or merely an "emanation" from him, is uncertain; but there seems no reason to doubt that Carneus means "the god of flocks and herds", in a wider sense, of the harvest and the vintage. The chief centre of his worship was Sparta, where the Carneia took place every year from the 7th to the 15th of the month Carneus. During this period all military operations were suspended.

The Oxyrhynchus hymn is the earliest known manuscript of a Christian Greek hymn to contain both lyrics and musical notation. The papyrus on which the hymn was written dates from around the end of the 3rd century AD. It is on Papyrus 1786 of the Oxyrhynchus papyri, now kept at the Papyrology Rooms of the Sackler Library, Oxford. The manuscript was discovered in 1918 in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, and later published in 1922.

Music was almost universally present in ancient Greek society, from marriages, funerals, and religious ceremonies to theatre, folk music, and the ballad-like reciting of epic poetry. This played an integral role in the lives of ancient Greeks. There are some fragments of actual Greek musical notation, many literary references, depictions on ceramics and relevant archaeological remains, such that some things can be known—or reasonably surmised—about what the music sounded like, the general role of music in society, the economics of music, the importance of a professional caste of musicians, etc.

In Greek mythology, Paean, Paeëon or Paieon (Παιήων), or Paeon or Paion (Παιών) was the physician of the gods.

The kithara, Latinized as cithara, was an ancient Greek musical instrument in the yoke lutes family. It was a seven-stringed professional version of the lyre, which was regarded as a rustic, or folk instrument, appropriate for teaching music to beginners. As opposed to the simpler lyre, the cithara was primarily used by professional musicians, called kitharodes. In modern Greek, the word kithara has come to mean "guitar", a word which etymologically stems from kithara.

2nd millennium BC in music - 1st millennium BC in music - 1st millennium in music

Prosodion in ancient Greece was a processional song to the altar of a deity, mainly Apollo or Artemis, sung ritually before the Paean hymn. It is one of the earliest musical types used by the Greeks. The prosodion was accompanied by the aulos, whereas the associated paean was accompanied by the kithara. Prosodia were composed by Alcman, Pindar, Simonides of Ceos, Bacchylides, Eumelus of Corinth, and Limenius, as well the various winners in art competitions (Mouseia). The etymology of the word is related to ὁδός hodos road and not with ᾠδή ôidê song. According to Soterichus, the music of the prosodia by Alcman, Pindar, Simonides, and Bacchylides was written in the Dorian tonos "because of its grandeur and dignity". The only complete surviving prosodion, however, is composed in the Lydian tonos.

A paean is a song or expression of thanksgiving, triumph, healing or praise.

In Greek mythology, Paean, Paeëon or Paieon, or Paeon or Paion may refer to the following characters:

In Greek mythology, Coronis is a Thessalian princess and a lover of the god Apollo. She was the daughter of Phlegyas, king of the Lapiths, and Cleophema. By Apollo she became the mother of Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine. While she was still pregnant, she slept with a mortal man named Ischys and was subsequently killed by either the god or his sister Artemis for her betrayal. After failing to heal her, Apollo rescued their unborn child by performing a caesarean section. She was turned into a constellation after her death.

References

- ↑ Paean, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon , at Perseus

- 1 2 Mycenaean Greek 𐀞𐀊𐀺𐀚, pa-ja-wo-ne /pajāwonei/ (dat.), written in Linear B and attested on the KN V 52 tablet found at Mycenaean Knossos, attests the name as referring to an individual Mycenaean deity. See John Chadwick, The Mycenaean World [Cambridge University Press] 1976, p. 88).

- ↑ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 1142 (see also pp. 1144 and 1159).

- ↑ Eustathius on Homer §1494; Virgil, Aeneid vii. 769.

- ↑ Both occasions are noted by Grace Macurdy, "The Derivation of the Greek Word Paean" Language 6, no. 4 (December 1930: 297-303), citation on 300.

- ↑ Grace Macurdy, "The Derivation of the Greek Word Paean", Language 6, no. 4 (December 1930: 297-303), written before the deciphering of Linear B, attributes an origin of paeon in the north of Greece, rather than Minoan Crete; she offered the quote from Nilsson, Greek Religion, p. 130.

- ↑ Farnell, The Cults of the Greek States (Oxford University Press, 1896)[ page needed ].

- ↑ Barry Strauss, The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter That Saved Greece—and Western Civilization (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004), p. 160

- ↑ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Rex Warner, Penguin Books LTD, p. 65

- ↑ Xenophon, The Persian Expedition. Translated by Rex Warner, Penguin Books LTD. Pg. 49

- ↑ Annie Bélis (ed.). 1992. Corpus des inscriptions de Delphes, vol. 3: "Les Hymnes à Apollon" (Paris: De Boccard, 1992), 48–49, 53–54; Egert Pöhlmann and Martin L. West, Documents of Ancient Greek Music: The Extant Melodies and Fragments, edited and transcribed with commentary by Egert Pöhlmann and Martin L. West (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2001), 71.

- ↑ Pearlman, Gary. "End of North Korea?". The Palm Beach Times . Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.