Pendleton Colliery was a coal mine operating on the Manchester Coalfield after the late 1820s on Whit Lane in Pendleton, Salford, then in the historic county of Lancashire, England.

Pendleton Colliery was a coal mine operating on the Manchester Coalfield after the late 1820s on Whit Lane in Pendleton, Salford, then in the historic county of Lancashire, England.

John Purcell Fitzgerald, Member of Parliament and estate owner, started to sink shafts to the Three Foot and Worsley Four Foot mines at Whit Lane, Pendleton on his estate in the late 1820s. [1] [2] The shafts were on the west side of the Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal. [3] George Stephenson's brother, Robert (1788–1837), supervised operations as manager and engineer until his death in 1837. [4] In 1832 he was able to report to Fitzgerald that the four foot seam had been reached. [1] [5] [6]

The original shaft was sunk to a depth of around 650 feet and in the first six months of 1832 the colliery produced nearly 27,000 tons of coal. [4] The shaft was closed after flooding in 1834. In 1835, Fitzgerald formed the Pendleton Colliery Company, with George Stephenson as a director, and leased nearby land from the Duchy of Lancaster for new mining works. In 1836, the colliery supplied at least 215,000 tons of coal to Manchester by road, 24 per cent of the city's total demand. [7] Robert Stephenson supervised the sinking of two eight-feet diameter shafts to deeper, drier seams below the Worsley Four Foot in 1836–37 [4] and a steam engine of around 40 horsepower was installed. The new shaft was on the east bank of the canal where a short branch terminated in the pit yard. In 1840 the shaft reached coal at a depth of 1,392 feet. [3] The new workings undertaken by the company were expected to generate profits of £14,000 per annum but the colliery suffered from problems relating to water ingress throughout its existence. [1] [2] [8]

By 1840 the coal faces of the Albert and Crombourke mines were 1,400 feet below the surface. [4] More flooding in 1843 caused the pit to close when it employed nearly 1,000 people and produced 1,000 tons of coal per day. [9] The lower sections of the new shafts, which were around 1,590 feet deep, were lined with cast iron tubbing in an attempt to restrain water ingress. A design flaw was being rectified at the time of the flooding, which newspapers attributed to the closure of two nearby collieries that had shut down due to flooding and the absence of their pumping mechanisms had increased the volume of water present. Newspapers reported that Fitzgerald's losses as a result of the ingress — which was initially termed a "destruction" by the Morning Post — were at least £50,000. [2] [8] By the end of 1843 a beam engine with a 75-inch stroke had been installed to clear the water. [3] The colliery was still closed in June 1846, by which time more than 157 million gallons of water had been pumped out and the coal lay 100 yards below the water level. [10] Mining operations recommenced in January 1847 and were marked with a celebratory procession through the streets of Manchester and Salford [11] but the disaster had ruined some of the company's directors and in 1848 Fitzgerald filed for bankruptcy. His son noted in 1843 that

My father, after spending £100,000 on a colliery, besides losses by everlasting rogues, runaway agents, etc., has just been drowned out of it ... So end the hopes of eighteen years; and he is near seventy, left without his only hobby! ... [H]e is come to the end of his purse. [1] [lower-alpha 1]

Jack Nadin says that the colliery was closed in 1848 [2] but D. R. Fisher says Fitzgerald continued mining somewhere and there are numerous newspaper advertisements after 1848 that list the address of Fitzgerald's agent, Hugh Higson, as being that of the colliery. Under the provisions of bankruptcy, the lease was offered for sale in 1852, which was the year that Fitzgerald died. The lease covered approximately 280 acres of land, the associated mineral rights and plant and machinery. At that time, the seams being worked were the Albert mine, the Binn mine, the New Six Foot and the Seven Foot. [1] [13]

Andrew Knowles and Sons bought the underlease in 1852. [14] The company developed the colliery by sinking new shafts on the east side of the canal in 1857 to access the Rams mine at 1,545 feet and the shafts on the west side of the canal were abandoned. [3] As the coal was worked from coal seams that dipped at 1-in-3, Pendleton became the deepest coal mine in the country when the workings reached 3,600 feet where the temperature at the coal face reached 100 degrees Fahrenheit. [4]

Andrew Knowles and Sons relined the upcast shaft in 1872 reducing its diameter to 7 feet 2 inches, giving Pendleton the record for the narrowest shaft. [4] In 1891 the company decided to modernise the colliery by sinking two 16 feet-diameter shafts but water from old workings broke through causing flooding and subsidence and the shafts were abandoned. [4] A screening plant and wagon loading facility were built on the canal's west bank alongside the Manchester and Bolton Railway line linked to the pit by a bridge built in 1894. [15] A small engine shed and sidings were built to connect with the railway by January 1895. A saddletank locomotive supplied by Manning Wardle in 1901 was named Knowles. [16]

In 1896 Pendleton Nos. 1 & 2 pits employed 441 underground and 126 surface workers [17] and in 1933 employed 272 underground and 117 on the surface. [18]

Ground upheaval in the Rams mine caused five deaths in 1925. [19]

The colliery became part of Manchester Collieries in 1929 by which time the Albert and Crombouke mines were exhausted. The new owners fitted new headgear to No. 1 shaft in 1931. [16] The colliery closed in 1939 when coal in the Rams mine was exhausted. [4] The colliery site was subsequently used by the Manchester Oxide Company to process spent iron oxide. [16]

Clifton Hall Colliery was one of two coal mines in Clifton on the Manchester Coalfield, historically in Lancashire which was incorporated into the City of Salford in Greater Manchester, England in 1974. Clifton Hall was notorious for an explosion in 1885 which killed around 178 men and boys.

Agecroft Colliery was a coal mine on the Manchester Coalfield that opened in 1844 in the Agecroft district of Pendlebury, Lancashire, England. It exploited the coal seams of the Middle Coal Measures of the Lancashire Coalfield. The colliery had two spells of use; the first between 1844 and 1932, when the most accessible coal seams were exploited, and a second lease of life after extensive development in the late 1950s to access the deepest seams.

Wet Earth Colliery was a coal mine located on the Manchester Coalfield, in Clifton, Greater Manchester. The colliery site is now the location of Clifton Country Park. The colliery has a unique place in British coal mining history; apart from being one of the earliest pits in the country, it is the place where engineer James Brindley made water run uphill.

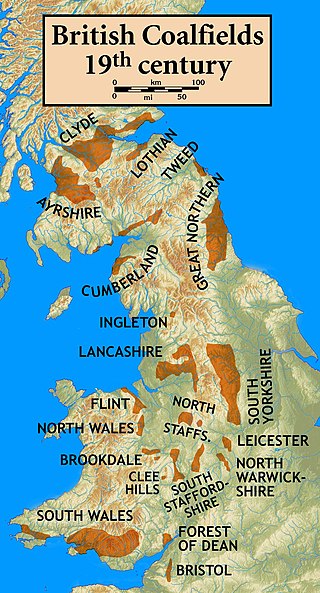

The Lancashire Coalfield in North West England was an important British coalfield. Its coal seams were formed from the vegetation of tropical swampy forests in the Carboniferous period over 300 million years ago.

The Astley and Tyldesley Collieries Company formed in 1900 owned coal mines on the Lancashire Coalfield south of the railway in Astley and Tyldesley, then in the historic county of Lancashire, England. The company became part of Manchester Collieries in 1929 and some of its collieries were nationalised in 1947.

Tyldesley Coal Company was a coal mining company formed in 1870 in Tyldesley, on the Manchester Coalfield in the historic county of Lancashire, England that had its origins in Yew Tree Colliery, the location for a mining disaster that killed 25 men and boys in 1858.

Bedford Colliery, also known as Wood End Pit, was a coal mine on the Manchester Coalfield in Bedford, Leigh, Lancashire, England. The colliery was owned by John Speakman, who started sinking two shafts on land at Wood End Farm in the northeast part of Bedford, south of the London and North Western Railway's Tyldesley Loopline in about 1874. Speakman's father owned Priestners, Bankfield, and Broadoak collieries in Westleigh. Bedford Colliery remained in the possession of the Speakman family until it was amalgamated with Manchester Collieries in 1929.

Great Boys Colliery was a coal mine operating on the Manchester Coalfield in the second half of the 19th century in Tyldesley, then in the historic county of Lancashire, England. It was sunk on Great Boys farm, which in 1778 was described as a "messuage with eight Cheshire acres of land" on the north side of Sale Lane west of the Colliers Arms public house. It was owned by William Atkin and sold in 1855 to mineowners, John Fletcher of Bolton and Samuel Scowcroft. By 1869 their partnership was dissolved and the company became John Fletcher and Sons in 1877. Shafts were sunk for a colliery on Pear Tree Farm on the corner of Mort Lane and Sale Lane which appear in the 1867 Mines Lists and became part of Great Boys Colliery. Fletcher and Schofield were granted permission to construct a mineral railway to join the London and North Western Railway's Tyldesley Loopline in 1868 but there is no evidence that it was built. The colliery closed before 1885. The colliery accessed the Brassey mine at about 170 yards and the Six Foot mine at 182 yards. The deeper coal seams were accessed by New Lester Colliery.

Fletcher, Burrows and Company was a coal mining company that owned collieries and cotton mills in Atherton, Greater Manchester, England. Gibfield, Howe Bridge and Chanters collieries exploited the coal mines (seams) of the middle coal measures in the Manchester Coalfield. The Fletchers built company housing at Hindsford and a model village at Howe Bridge which included pithead baths and a social club for its workers. The company became part of Manchester Collieries in 1929. The collieries were nationalised in 1947 becoming part of the National Coal Board.

Bridgewater Collieries originated from the coal mines on the Manchester Coalfield in Worsley in the historic county of Lancashire owned by Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater in the second half of the 18th century. After the Duke's death in 1803 his estate was managed by the Bridgewater Trustees until the 3rd Earl of Ellesmere inherited the estates in 1903. Bridgewater Collieries was formed in 1921 by the 4th Earl. The company merged with other prominent mining companies to form Manchester Collieries in 1929.

New Manchester or The City was an isolated mining community on the Manchester Coalfield north of Mosley Common in the Tyldesley township, England. It lies west of a boundary stone at Ellenbrook which marks the ancient boundary of the Hundreds of Salford and West Derby, the boundary of Eccles and Leigh ecclesiastical parishes, Tyldesley, Worsley and Little Hulton townships and the metropolitan districts of Wigan and Salford. The route of the Roman road from Manchester to Wigan and the Tyldesley Loopline passed south of the village. The Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway's Manchester to Southport line passed to the north.

Andrew Knowles and Sons was a coal mining company that operated on the Manchester Coalfield in and around Clifton near Pendlebury, in the historic county of Lancashire, England.

Astley Green Colliery was a coal mine in Astley, Greater Manchester, then in the historic county of Lancashire, England. It was the last colliery to be sunk in Astley. Sinking commenced in 1908 by the Pilkington Colliery Company, a subsidiary of the Clifton and Kersley Coal Company, at the southern edge of the Manchester Coalfield, working the Middle Coal Measures where they dipped under the Permian age rocks under Chat Moss. The colliery was north of the Bridgewater Canal. In 1929 it became part of Manchester Collieries, and in 1947 was nationalised and integrated into the National Coal Board. It closed in 1970, and is now Astley Green Colliery Museum.

Chanters Colliery was a coal mine which was part of the Fletcher, Burrows and Company's collieries at Hindsford in Atherton, Greater Manchester, then in the historic county of Lancashire, England.

Nelson Pit was a coal mine operating on the Manchester Coalfield from the 1830s or 1840s in Shakerley, Tyldesley, Greater Manchester, then in the historic county of Lancashire, England.

Bradford Colliery was a coal mine in Bradford, Manchester, England. Although part of the Manchester Coalfield, the seams of the Bradford Coalfield correspond more closely to those of the Oldham Coalfield. The Bradford Coalfield is crossed by a number of fault lines, principally the Bradford Fault, which was reactivated by mining activity in the mid-1960s.

The Burnley Coalfield is the most northerly portion of the Lancashire Coalfield. Surrounding Burnley, Nelson, Blackburn and Accrington, it is separated from the larger southern part by an area of Millstone Grit that forms the Rossendale anticline. Occupying a syncline, it stretches from Blackburn past Colne to the Yorkshire border where its eastern flank is the Pennine anticline.

Bank Hall Colliery was a coal mine on the Burnley Coalfield in Burnley, Lancashire near the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. Sunk in the late 1860s, it was the town's largest and deepest pit and had a life of more than 100 years.

Hapton Valley Colliery was a coal mine on the edge of Hapton near Burnley in Lancashire, England. Its first shafts were sunk in the early 1850s and it had a life of almost 130 years, surviving to be the last deep mine operating on the Burnley Coalfield.

Notes

Citations

Bibliography