Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, magnetism is one of two aspects of electromagnetism.

A magnetic field is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to the magnetic field. A permanent magnet's magnetic field pulls on ferromagnetic materials such as iron, and attracts or repels other magnets. In addition, a nonuniform magnetic field exerts minuscule forces on "nonmagnetic" materials by three other magnetic effects: paramagnetism, diamagnetism, and antiferromagnetism, although these forces are usually so small they can only be detected by laboratory equipment. Magnetic fields surround magnetized materials, electric currents, and electric fields varying in time. Since both strength and direction of a magnetic field may vary with location, it is described mathematically by a function assigning a vector to each point of space, called a vector field.

A magnet is a material or object that produces a magnetic field. This magnetic field is invisible but is responsible for the most notable property of a magnet: a force that pulls on other ferromagnetic materials, such as iron, steel, nickel, cobalt, etc. and attracts or repels other magnets.

Timeline of electromagnetism and classical optics lists, within the history of electromagnetism, the associated theories, technology, and events.

A terrella is a small magnetised model ball representing the Earth, that is thought to have been invented by the English physician William Gilbert while investigating magnetism, and further developed 300 years later by the Norwegian scientist and explorer Kristian Birkeland, while investigating the aurora.

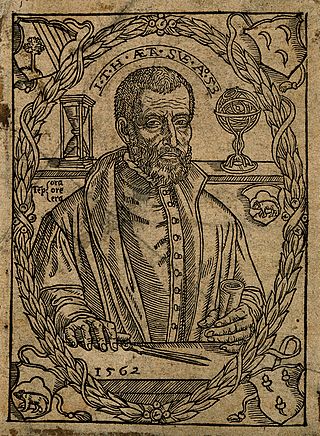

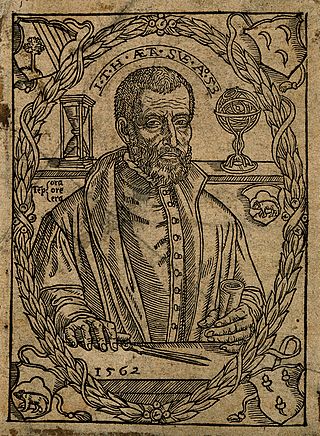

William Gilbert, also known as Gilberd, was an English physician, physicist and natural philosopher. He passionately rejected both the prevailing Aristotelian philosophy and the Scholastic method of university teaching. He is remembered today largely for his book De Magnete (1600).

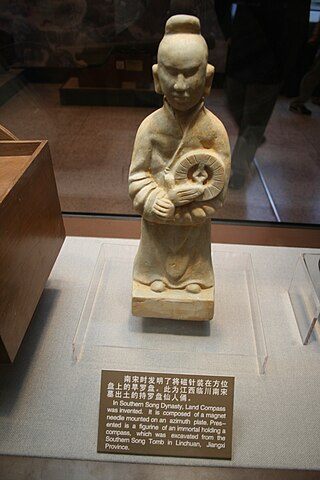

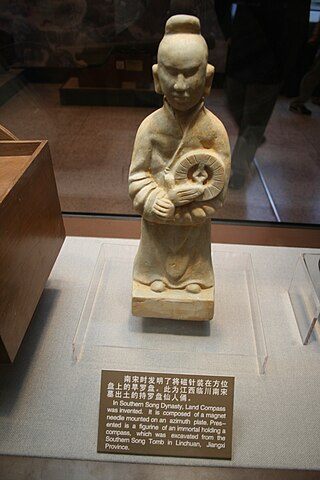

Lodestones are naturally magnetized pieces of the mineral magnetite. They are naturally occurring magnets, which can attract iron. The property of magnetism was first discovered in antiquity through lodestones. Pieces of lodestone, suspended so they could turn, were the first magnetic compasses, and their importance to early navigation is indicated by the name lodestone, which in Middle English means "course stone" or "leading stone", from the now-obsolete meaning of lode as "journey, way".

Medieval technology is the technology in medieval Europe under Christian rule. After the Renaissance of the 12th century, medieval Europe saw a radical change in the rate of new inventions, innovations in the ways of managing traditional means of production, and economic growth. The period saw major technological advances, including the adoption of gunpowder, the invention of vertical windmills, spectacles, mechanical clocks, and greatly improved water mills, building techniques, and agriculture in general.

De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure is a scientific work published in 1600 by the English physician and scientist William Gilbert. A highly influential and successful book, it exerted an immediate influence on many contemporary writers, including Francis Godwin and Mark Ridley.

Jean Taisnier, surnamed Hannonius, was a Wallonian musician, mathematician and astrologer who published a number of works and taught in various European cities and universities. In some sources he is mis-named Jean Fuisnier. He was for some time schoolmaster of the boys of the Chapel (Sacellanus) in the court of Emperor Charles V. By 1559 he styled himself "Poet Laureate", and "Doctor of both Laws", but upon what authority is unknown. While he propounded a general theory of Mathematics in four "Quantities" of Astronomy, Geometry, Arithmetic and Music, and aimed to publish a general exposition of them, he became preoccupied with astrology and cheiromancy, and neglected to publish his advertized Treatise on Music which might have been the most interesting of all his works. His unacknowledged use of the work of other authors has incurred the accusation of plagiarism. He was the great-uncle of David Teniers the Elder.

Giambattista (Gianbattista) Benedetti was an Italian mathematician from Venice who was also interested in physics, mechanics, the construction of sundials, and the science of music.

Leonardo Garzoni was a Jesuit natural philosopher.

In physics, Gauss's law for magnetism is one of the four Maxwell's equations that underlie classical electrodynamics. It states that the magnetic field B has divergence equal to zero, in other words, that it is a solenoidal vector field. It is equivalent to the statement that magnetic monopoles do not exist. Rather than "magnetic charges", the basic entity for magnetism is the magnetic dipole.

A magnet motor or magnetic motor is a type of perpetual motion machine, which is intended to generate a rotation by means of permanent magnets in stator and rotor without external energy supply. Such a motor is theoretically as well as practically not realizable. The idea of functioning magnetic motors has been promoted by various hobbyists. It can be regarded as pseudoscience. There are frequent references to free energy and sometimes even links to esotericism.

Peregrinus Peak is a peak along the north side of Airy Glacier, 3 nautical miles (6 km) southeast of Mount Timosthenes, in central Antarctic Peninsula. Photographed from the air by Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition (RARE) November 27, 1947. Surveyed by Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (FIDS) in December 1958. Named by United Kingdom Antarctic Place-Names Committee (UK-APC) after Petrus Peregrinus de Maricourt, of Luceria, author of Epistola de magnete (1269), the first scientific treatise on the magnet.

The history of geomagnetism is concerned with the history of the study of Earth's magnetic field. It encompasses the history of navigation using compasses, studies of the prehistoric magnetic field, and applications to plate tectonics.

Petrus is the Latin form of the Greek name Πέτρος (pétros) meaning "rock", and is the common English prefix "petro-" used to describe rock-based substances, like petros-oleum or "rock oil." As the source of Peter, it is a common name for people from antiquity through the medieval era. In the Netherlands, Belgium and South Africa it remained a very common given name, though in daily life, many use less formal forms like Peter, Pierre, Piet and Pieter.

The compass is a magnetometer used for navigation and orientation that shows direction in regards to the geographic cardinal points. The structure of a compass consists of the compass rose, which displays the four main directions on it: East (E), South (S), West (W) and North (N). The angle increases in the clockwise position. North corresponds to 0°, so east is 90°, south is 180° and west is 270°.

Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica is a 1641 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was dedicated to Emperor Ferdinand III and printed in Rome by Hermann Scheuss. It developed the ideas set out in his earlier Ars Magnesia and argued that the universe is governed by universal physical forces of attraction and repulsion. These were, as described in the motto in the book's first illustration, 'hidden nodes' of connection. The force that drew things together in the physical world was, he argued, the same force that drew people's souls towards God. The work is divided into three books: 1.De natura et facultatibus magnetis, 2.Magnes applicatus, 3.Mundus sive catena magnetica. It is noted for the first use of the term 'electromagnetism'.

Raymond of Marseilles was a French astronomer and astrologer who is known only from his manuscripts on the use of astrolabes and translations of Arab astronomical texts of the period. His manuscript on astrolabes Traite de l'astrolabe or Vite presentis indutias silentio, a copy of which is in Paris served as a source for European astronomers in the Medieval period. The texts, originally of unknown authorship, were noted by Pierre Duhem in 1915 and in the 1920s by Lynn Thorndike and Charles Homer Haskins. The Paris manuscript which is the most complete version was found by Emmanuel Poulle in 1954. Another work was the first volume of Opera omnia which included Liber cursuum planetarum. Raymond's work included translations of the astronomical tables of al-Zarqālī. In 1972 another text, Liber judiciorum, on astrology was discovered by Marie-Thérèse d’Alverny.