Related Research Articles

Fluorescence is one of two kinds of emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. When exposed to ultraviolet radiation, many substances will glow (fluoresce) with colored visible light. The color of the light emitted depends on the chemical composition of the substance. Fluorescent materials generally cease to glow nearly immediately when the radiation source stops. This distinguishes them from the other type of light emission, phosphorescence. Phosphorescent materials continue to emit light for some time after the radiation stops.

Fluorescence spectroscopy is a type of electromagnetic spectroscopy that analyzes fluorescence from a sample. It involves using a beam of light, usually ultraviolet light, that excites the electrons in molecules of certain compounds and causes them to emit light; typically, but not necessarily, visible light. A complementary technique is absorption spectroscopy. In the special case of single molecule fluorescence spectroscopy, intensity fluctuations from the emitted light are measured from either single fluorophores, or pairs of fluorophores.

A fluorophore is a fluorescent chemical compound that can re-emit light upon light excitation. Fluorophores typically contain several combined aromatic groups, or planar or cyclic molecules with several π bonds.

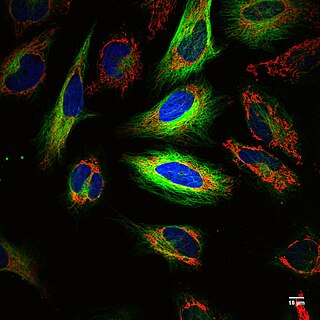

Immunofluorescence(IF) is a light microscopy-based technique that allows detection and localization of a wide variety of target biomolecules within a cell or tissue at a quantitative level. The technique utilizes the binding specificity of antibodies and antigens. The specific region an antibody recognizes on an antigen is called an epitope. Several antibodies can recognize the same epitope but differ in their binding affinity. The antibody with the higher affinity for a specific epitope will surpass antibodies with a lower affinity for the same epitope.

Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), fluorescence resonance energy transfer, resonance energy transfer (RET) or electronic energy transfer (EET) is a mechanism describing energy transfer between two light-sensitive molecules (chromophores). A donor chromophore, initially in its electronic excited state, may transfer energy to an acceptor chromophore through nonradiative dipole–dipole coupling. The efficiency of this energy transfer is inversely proportional to the sixth power of the distance between donor and acceptor, making FRET extremely sensitive to small changes in distance.

A total internal reflection fluorescence microscope (TIRFM) is a type of microscope with which a thin region of a specimen, usually less than 200 nanometers can be observed.

A fluorescence microscope is an optical microscope that uses fluorescence instead of, or in addition to, scattering, reflection, and attenuation or absorption, to study the properties of organic or inorganic substances. "Fluorescence microscope" refers to any microscope that uses fluorescence to generate an image, whether it is a simple set up like an epifluorescence microscope or a more complicated design such as a confocal microscope, which uses optical sectioning to get better resolution of the fluorescence image.

Fluorescence-lifetime imaging microscopy or FLIM is an imaging technique based on the differences in the exponential decay rate of the photon emission of a fluorophore from a sample. It can be used as an imaging technique in confocal microscopy, two-photon excitation microscopy, and multiphoton tomography.

Two-photon excitation microscopy is a fluorescence imaging technique that is particularly well-suited to image scattering living tissue of up to about one millimeter in thickness. Unlike traditional fluorescence microscopy, where the excitation wavelength is shorter than the emission wavelength, two-photon excitation requires simultaneous excitation by two photons with longer wavelength than the emitted light. The laser is focused onto a specific location in the tissue and scanned across the sample to sequentially produce the image. Due to the non-linearity of two-photon excitation, mainly fluorophores in the micrometer-sized focus of the laser beam are excited, which results in the spatial resolution of the image. This contrasts with confocal microscopy, where the spatial resolution is produced by the interaction of excitation focus and the confined detection with a pinhole.

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) is a statistical analysis, via time correlation, of stationary fluctuations of the fluorescence intensity. Its theoretical underpinning originated from L. Onsager's regression hypothesis. The analysis provides kinetic parameters of the physical processes underlying the fluctuations. One of the interesting applications of this is an analysis of the concentration fluctuations of fluorescent particles (molecules) in solution. In this application, the fluorescence emitted from a very tiny space in solution containing a small number of fluorescent particles (molecules) is observed. The fluorescence intensity is fluctuating due to Brownian motion of the particles. In other words, the number of the particles in the sub-space defined by the optical system is randomly changing around the average number. The analysis gives the average number of fluorescent particles and average diffusion time, when the particle is passing through the space. Eventually, both the concentration and size of the particle (molecule) are determined. Both parameters are important in biochemical research, biophysics, and chemistry.

Autofluorescence is the natural emission of light by biological structures such as mitochondria and lysosomes when they have absorbed light, and is used to distinguish the light originating from artificially added fluorescent markers (fluorophores).

Stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy is one of the techniques that make up super-resolution microscopy. It creates super-resolution images by the selective deactivation of fluorophores, minimizing the area of illumination at the focal point, and thus enhancing the achievable resolution for a given system. It was developed by Stefan W. Hell and Jan Wichmann in 1994, and was first experimentally demonstrated by Hell and Thomas Klar in 1999. Hell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2014 for its development. In 1986, V.A. Okhonin had patented the STED idea. This patent was unknown to Hell and Wichmann in 1994.

Fluorescence anisotropy or fluorescence polarization is the phenomenon where the light emitted by a fluorophore has unequal intensities along different axes of polarization. Early pioneers in the field include Aleksander Jablonski, Gregorio Weber, and Andreas Albrecht. The principles of fluorescence polarization and some applications of the method are presented in Lakowicz's book.

The DyLight Fluor family of fluorescent dyes are produced by Dyomics in collaboration with Thermo Fisher Scientific. DyLight dyes are typically used in biotechnology and research applications as biomolecule, cell and tissue labels for fluorescence microscopy, cell biology or molecular biology.

Fluorescence is used in the life sciences generally as a non-destructive way of tracking or analysing biological molecules. Some proteins or small molecules in cells are naturally fluorescent, which is called intrinsic fluorescence or autofluorescence. Alternatively, specific or general proteins, nucleic acids, lipids or small molecules can be "labelled" with an extrinsic fluorophore, a fluorescent dye which can be a small molecule, protein or quantum dot. Several techniques exist to exploit additional properties of fluorophores, such as fluorescence resonance energy transfer, where the energy is passed non-radiatively to a particular neighbouring dye, allowing proximity or protein activation to be detected; another is the change in properties, such as intensity, of certain dyes depending on their environment allowing their use in structural studies.

Super-resolution microscopy is a series of techniques in optical microscopy that allow such images to have resolutions higher than those imposed by the diffraction limit, which is due to the diffraction of light. Super-resolution imaging techniques rely on the near-field or on the far-field. Among techniques that rely on the latter are those that improve the resolution only modestly beyond the diffraction-limit, such as confocal microscopy with closed pinhole or aided by computational methods such as deconvolution or detector-based pixel reassignment, the 4Pi microscope, and structured-illumination microscopy technologies such as SIM and SMI.

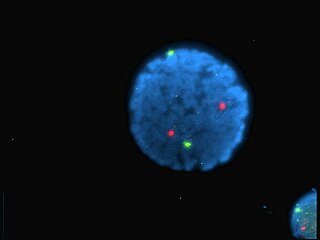

Single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer is a biophysical technique used to measure distances at the 1-10 nanometer scale in single molecules, typically biomolecules. It is an application of FRET wherein a pair of donor and acceptor fluorophores are excited and detected at a single molecule level. In contrast to "ensemble FRET" which provides the FRET signal of a high number of molecules, single-molecule FRET is able to resolve the FRET signal of each individual molecule. The variation of the smFRET signal is useful to reveal kinetic information that an ensemble measurement cannot provide, especially when the system is under equilibrium with no ensemble/bulk signal change. Heterogeneity among different molecules can also be observed. This method has been applied in many measurements of intramolecular dynamics such as DNA/RNA/protein folding/unfolding and other conformational changes, and intermolecular dynamics such as reaction, binding, adsorption, and desorption that are particularly useful in chemical sensing, bioassays, and biosensing.

Within the scientific study of a molecule's color, Fluorescence intensity decay shape microscopy (FIDSAM) is a fluorescence microscope technique, which utilizes the time evolution of fluorescence emission after a pulsed excitation to analyse the decay statistics of an excited chromophore. The main application of FIDSAM is the discrimination of unspecific autofluorescent background signal from the target signal of a dedicated chromophore.

Photo-activated localization microscopy and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) are widefield fluorescence microscopy imaging methods that allow obtaining images with a resolution beyond the diffraction limit. The methods were proposed in 2006 in the wake of a general emergence of optical super-resolution microscopy methods, and were featured as Methods of the Year for 2008 by the Nature Methods journal. The development of PALM as a targeted biophysical imaging method was largely prompted by the discovery of new species and the engineering of mutants of fluorescent proteins displaying a controllable photochromism, such as photo-activatible GFP. However, the concomitant development of STORM, sharing the same fundamental principle, originally made use of paired cyanine dyes. One molecule of the pair, when excited near its absorption maximum, serves to reactivate the other molecule to the fluorescent state.

Fluorescence imaging is a type of non-invasive imaging technique that can help visualize biological processes taking place in a living organism. Images can be produced from a variety of methods including: microscopy, imaging probes, and spectroscopy.

References

- ↑ Demchenko, Alexander P (2020-02-20). "Photobleaching of organic fluorophores: quantitative characterization, mechanisms, protection". Methods and Applications in Fluorescence. 8 (2): 022001. Bibcode:2020MApFl...8b2001D. doi:10.1088/2050-6120/ab7365. ISSN 2050-6120. PMID 32028269. S2CID 211048171.

- ↑ "Fluorophore Photobleaching Literature References".