Applications outside the membrane

FRAP can also be used to monitor proteins outside the membrane. After the protein of interest is made fluorescent, generally by expression as a GFP fusion protein, a confocal microscope is used to photobleach and monitor a region of the cytoplasm, [3] mitotic spindle, nucleus, or another cellular structure. [8] [9] The mean fluorescence in the region can then be plotted versus time since the photobleaching, and the resulting curve can yield kinetic coefficients, such as those for the protein's binding reactions and/or the protein's diffusion coefficient in the medium where it is being monitored. [10] Often the only dynamics considered are diffusion and binding/unbinding interactions, however, in principle proteins can also move via flow, i.e., undergo directed motion, and this was recognized very early by Axelrod et al. [1] This could be due to flow of the cytoplasm or nucleoplasm, or transport along filaments in the cell such as microtubules by molecular motors.

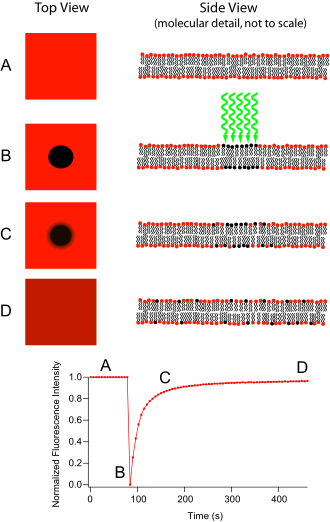

The analysis is most simple when the fluorescence recovery is limited by either the rate of diffusion into the bleached area or by rate at which bleached proteins unbind from their binding sites within the bleached area, and are replaced by fluorescent protein. Let us look at these two limits, for the common case of bleaching a GFP fusion protein in a living cell.

Diffusion-limited fluorescence recovery

For a circular bleach spot of radius  and diffusion-dominated recovery, the fluorescence is described by an equation derived by Soumpasis [11] (which involves modified Bessel functions

and diffusion-dominated recovery, the fluorescence is described by an equation derived by Soumpasis [11] (which involves modified Bessel functions  and

and  )

)

with  the characteristic timescale for diffusion, and

the characteristic timescale for diffusion, and  is the time.

is the time.  is the normalized fluorescence (goes to 1 as

is the normalized fluorescence (goes to 1 as  goes to infinity). The diffusion timescale for a bleached spot of radius

goes to infinity). The diffusion timescale for a bleached spot of radius  is

is  , with D the diffusion coefficient.

, with D the diffusion coefficient.

Note that this is for an instantaneous bleach with a step function profile, i.e., the fraction  of protein assumed to be bleached instantaneously at time

of protein assumed to be bleached instantaneously at time  is

is  , and

, and  , for

, for  is the distance from the centre of the bleached area. It is also assumed that the recovery can be modelled by diffusion in two dimensions, that is also both uniform and isotropic. In other words, that diffusion is occurring in a uniform medium so the effective diffusion constant D is the same everywhere, and that the diffusion is isotropic, i.e., occurs at the same rate along all axes in the plane.

is the distance from the centre of the bleached area. It is also assumed that the recovery can be modelled by diffusion in two dimensions, that is also both uniform and isotropic. In other words, that diffusion is occurring in a uniform medium so the effective diffusion constant D is the same everywhere, and that the diffusion is isotropic, i.e., occurs at the same rate along all axes in the plane.

In practice, in a cell none of these assumptions will be strictly true.

- Bleaching will not be instantaneous. Particularly if strong bleaching of a large area is required, bleaching may take a significant fraction of the diffusion timescale

. Then a significant fraction of the bleached protein will diffuse out of the bleached region actually during bleaching. Failing to take account of this will introduce a significant error into D. [12] [13] [14]

. Then a significant fraction of the bleached protein will diffuse out of the bleached region actually during bleaching. Failing to take account of this will introduce a significant error into D. [12] [13] [14] - The bleached profile will not be a radial step function. If the bleached spot is effectively a single pixel then the bleaching as a function of position will typically be diffraction limited and determined by the optics of the confocal laser scanning microscope used. This is not a radial step function and also varies along the axis perpendicular to the plane.

- Cells are of course three-dimensional not two-dimensional, as is the bleached volume. Neglecting diffusion out of the plane (we take this to be the xy plane) will be a reasonable approximation only if the fluorescence recovers predominantly via diffusion in this plane. This will be true, for example, if a cylindrical volume is bleached with the axis of the cylinder along the z axis and with this cylindrical volume going through the entire height of the cell. Then diffusion along the z axis does not cause fluorescence recovery as all protein is bleached uniformly along the z axis, and so neglecting it, as Soumpasis' equation does, is harmless. However, if diffusion along the z axis does contribute to fluorescence recovery then it must be accounted for.

- There is no reason to expect the cell cytoplasm or nucleoplasm to be completely spatially uniform or isotropic.

Thus, the equation of Soumpasis is just a useful approximation, that can be used when the assumptions listed above are good approximations to the true situation, and when the recovery of fluorescence is indeed limited by the timescale of diffusion  . Note that just because the Soumpasis can be fitted adequately to data does not necessarily imply that the assumptions are true and that diffusion dominates recovery.

. Note that just because the Soumpasis can be fitted adequately to data does not necessarily imply that the assumptions are true and that diffusion dominates recovery.

Reaction-limited recovery

The equation describing the fluorescence as a function of time is particularly simple in another limit. If a large number of proteins bind to sites in a small volume such that there the fluorescence signal is dominated by the signal from bound proteins, and if this binding is all in a single state with an off rate koff, then the fluorescence as a function of time is given by [15]

Note that the recovery depends on the rate constant for unbinding, koff, only. It does not depend on the on rate for binding. Although it does depend on a number of assumptions [15]

- The on rate must be sufficiently large in order for the local concentration of bound protein to greatly exceed the local concentration of free protein, and so allow us to neglect the contribution to f of the free protein.

- The reaction is a simple bimolecular reaction, where the protein binds to localised sites that do not move significantly during recovery

- Exchange is much slower than diffusion (or whatever transport mechanism is responsible for mobility), as only then does the diffusing fraction recovery rapidly and then acts as the source of fluorescent protein that binds and replaces the bound bleached protein and so increases the fluorescence. With r the radius of the bleached spot, this means that the equation is only valid if the bound lifetime

.

.

If all these assumptions are satisfied, then fitting an exponential to the recovery curve will give the off rate constant, koff. However, other dynamics can give recovery curves similar to exponentials, so fitting an exponential does not necessarily imply that recovery is dominated by a simple bimolecular reaction. One way to distinguish between recovery with a rate determined by unbinding and recovery that is limited by diffusion, is to note that the recovery rate for unbinding-limited recovery is independent of the size of the bleached area r, while it scales as  , for diffusion-limited recovery. Thus if a small and a large area are bleached, if recovery is limited by unbinding then the recovery rates will be the same for the two sizes of bleached area, whereas if recovery is limited by diffusion then it will be much slower for the larger bleached area.

, for diffusion-limited recovery. Thus if a small and a large area are bleached, if recovery is limited by unbinding then the recovery rates will be the same for the two sizes of bleached area, whereas if recovery is limited by diffusion then it will be much slower for the larger bleached area.

Diffusion and reaction

In general, the recovery of fluorescence will not be dominated by either simple isotropic diffusion, or by a single simple unbinding rate. There will be both diffusion and binding, and indeed the diffusion constant may not be uniform in space, and there may be more than one type of binding sites, and these sites may also have a non-uniform distribution in space. Flow processes may also be important. This more complex behavior implies that a model with several parameters is required to describe the data; models with only either a single diffusion constant D or a single off rate constant, koff, are inadequate.

There are models with both diffusion and reaction. [2] Unfortunately, a single FRAP curve may provide insufficient evidence to reliably and uniquely fit (possibly noisy) experimental data. Sadegh Zadeh et al. [16] have shown that FRAP curves can be fitted by different pairs of values of the diffusion constant and the on-rate constant, or, in other words, that fits to the FRAP are not unique. This is in three-parameter (on-rate constant, off-rate constant and diffusion constant) fits. Fits that are not unique, are not generally useful.

Thus for models with a number of parameters, a single FRAP experiment may be insufficient to estimate all the model parameters. Then more data is required, e.g., by bleaching areas of different sizes, [14] determining some model parameters independently, etc.