Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal. In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types of material. As a method of printmaking, it is, along with engraving, the most important technique for old master prints, and remains in wide use today. In a number of modern variants such as microfabrication etching and photochemical milling, it is a crucial technique in modern technology, including circuit boards.

Printmaking is the process of creating artworks by printing, normally on paper, but also on fabric, wood, metal, and other surfaces. "Traditional printmaking" normally covers only the process of creating prints using a hand processed technique, rather than a photographic reproduction of a visual artwork which would be printed using an electronic machine ; however, there is some cross-over between traditional and digital printmaking, including risograph.

A printed circuit board (PCB), also called printed wiring board (PWB), is a medium used to connect or "wire" components to one another in a circuit. It takes the form of a laminated sandwich structure of conductive and insulating layers: each of the conductive layers is designed with a pattern of traces, planes and other features etched from one or more sheet layers of copper laminated onto and/or between sheet layers of a non-conductive substrate. Electrical components may be fixed to conductive pads on the outer layers in the shape designed to accept the component's terminals, generally by means of soldering, to both electrically connect and mechanically fasten them to it. Another manufacturing process adds vias, plated-through holes that allow interconnections between layers.

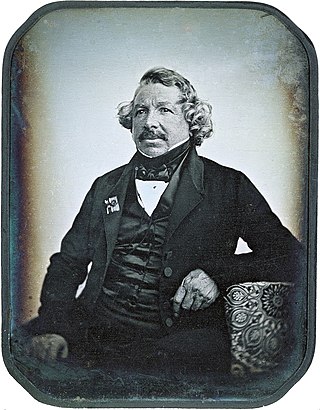

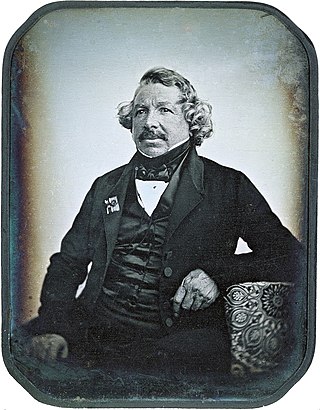

Daguerreotype was the first publicly available photographic process; it was widely used during the 1840s and 1850s. "Daguerreotype" also refers to an image created through this process.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce was a French inventor and one of the earliest pioneers of photography. Niépce developed heliography, a technique he used to create the world's oldest surviving products of a photographic process. In the mid-1820s, he used a primitive camera to produce the oldest surviving photograph of a real-world scene. Among Niépce's other inventions was the Pyréolophore, one of the world's first internal combustion engines, which he conceived, created, and developed with his older brother Claude Niépce.

Aquatint is an intaglio printmaking technique, a variant of etching that produces areas of tone rather than lines. For this reason it has mostly been used in conjunction with etching, to give both lines and shaded tone. It has also been used historically to print in colour, both by printing with multiple plates in different colours, and by making monochrome prints that were then hand-coloured with watercolour.

Frederic Eugene Ives was a U.S. inventor who was born in Litchfield, Connecticut. In 1874–78 he had charge of the photographic laboratory at Cornell University. He moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where in 1885 he was one of the founding members of the Photographic Society of Philadelphia. He was awarded the Franklin Institute's Elliott Cresson Medal in 1893, the Edward Longstreth Medal in 1903, and the John Scott Medal in 1887, 1890, 1904 and 1906. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1922. His son Herbert E. Ives was a pioneer of television and telephotography, including color facsimile.

Rotogravure is a type of intaglio printing process, which involves engraving the image onto an image carrier. In gravure printing, the image is engraved onto a cylinder because, like offset printing and flexography, it uses a rotary printing press.

Photogravure is a process for printing photographs, also sometimes used for reproductive intaglio printmaking. It is a photo-mechanical process whereby a copper plate is grained and then coated with a light-sensitive gelatin tissue which had been exposed to a film positive, and then etched, resulting in a high quality intaglio plate that can reproduce detailed continuous tones of a photograph.

KPR, originally known as Kodak Photoresist, is a photosensitive material used in photoengraving, Photogravure and photolithography. Once dried, KPR can be dissolved by several solvents. However, after exposure to strong ultraviolet light, it hardens and becomes insoluble by some of these solvents. It is also resistant to acid, ferric chloride and other chemicals used to etch metals.

Intaglio is the family of printing and printmaking techniques in which the image is incised into a surface and the incised line or sunken area holds the ink. It is the direct opposite of a relief print where the parts of the matrix that make the image stand above the main surface.

Heliography from helios, meaning "sun", and graphein (γράφειν), "writing") is the photographic process invented, and named thus, by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce around 1822, which he used to make the earliest known surviving photograph from nature, View from the Window at Le Gras, and the first realisation of photoresist as means to reproduce artworks through inventions of photolithography and photogravure.

Zincography was a planographic printing process that used zinc plates. Alois Senefelder first mentioned zinc's lithographic use as a substitute for Bavarian limestone in his 1801 English patent specifications. In 1834, Federico Lacelli patented a zincographic printing process, producing large maps called géoramas. In 1837–1842, Eugène-Florent Kaeppelin (1805–1865) perfected the process to create a large polychrome geologic map.

Steel engraving is a technique for printing illustrations based on steel instead of copper. It has been rarely used in artistic printmaking, although it was much used for reproductions in the 19th century. Steel engraving was introduced in 1792 by Jacob Perkins (1766–1849), an American inventor, for banknote printing. When Perkins moved to London in 1818, the technique was adapted in 1820 by Charles Warren and especially by Charles Heath (1785–1848) for Thomas Campbell's Pleasures of Hope, which contained the first published plates engraved on steel. The new technique only partially replaced the other commercial techniques of that time such as wood engraving, copper engraving and later lithography.

Etching is used in microfabrication to chemically remove layers from the surface of a wafer during manufacturing. Etching is a critically important process module in fabrication, and every wafer undergoes many etching steps before it is complete.

Bitumen of Judea is a naturally occurring asphalt that has been put to many uses since ancient times.

Photochemical machining (PCM), also known as photochemical milling or photo etching, is a chemical milling process used to fabricate sheet metal components using a photoresist and etchants to corrosively machine away selected areas. This process emerged in the 1960s as an offshoot of the printed circuit board industry. Photo etching can produce highly complex parts with very fine detail accurately and economically.

Stipple engraving is a technique used to create tone in an intaglio print by distributing a pattern of dots of various sizes and densities across the image. The pattern is created on the printing plate either in engraving by gouging out the dots with a burin, or through an etching process. Stippling was used as an adjunct to conventional line engraving and etching for over two centuries, before being developed as a distinct technique in the mid-18th century.

Chemical milling or industrial etching is the subtractive manufacturing process of using baths of temperature-regulated etching chemicals to remove material to create an object with the desired shape. Other names for chemical etching include photo etching, chemical etching, photo chemical etching and photochemical machining. It is mostly used on metals, though other materials are increasingly important. It was developed from armor-decorating and printing etching processes developed during the Renaissance as alternatives to engraving on metal. The process essentially involves bathing the cutting areas in a corrosive chemical known as an etchant, which reacts with the material in the area to be cut and causes the solid material to be dissolved; inert substances known as maskants are used to protect specific areas of the material as resists.

Carbon tissue is a gelatin-based emulsion used as a photoresist in the chemical etching (photoengraving) of gravure cylinders for printing. This was introduced by British physicist and chemist Joseph Swan in 1864. It has been used in photographic reproduction since the early days of photography.