Related Research Articles

Francesco Maurizio Cossiga was an Italian politician. A member of Christian Democracy, he was prime minister of Italy from 1979 to 1980 and the president of Italy from 1985 to 1992. Cossiga is widely considered one of the most prominent and influential politicians of the First Italian Republic.

Aldo Romeo Luigi Moro was an Italian statesman and prominent member of Christian Democracy (DC) and its centre-left wing. He served as prime minister of Italy in five terms from December 1963 to June 1968 and from November 1974 to July 1976.

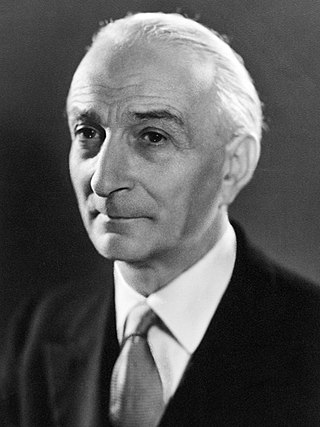

Antonio Segni was an Italian politician and statesman who served as the president of Italy from May 1962 to December 1964, and as the prime minister of Italy in two distinct terms between 1955 and 1960.

Amintore Fanfani was an Italian politician and statesman, who served as 32nd prime minister of Italy for five separate terms. He was one of the best-known Italian politicians after the Second World War and a historical figure of the left-wing faction of Christian Democracy. He is also considered one of the founders of the modern Italian centre-left.

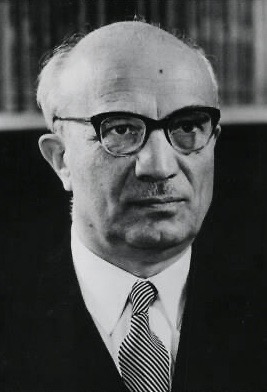

Giulio Andreotti was an Italian politician and statesman who served as the 41st prime minister of Italy in seven governments, and was leader of the Christian Democracy party and its right-wing; he was the sixth-longest-serving prime minister since the Italian unification and the second-longest-serving post-war prime minister. Andreotti is widely considered the most powerful and prominent politician of the First Republic.

Giovanni Leone was an Italian politician, jurist and university professor. A founding member of Christian Democracy (DC), Leone served as the president of Italy from December 1971 until June 1978. He also briefly served as Prime Minister of Italy from June to December 1963 and again from June to December 1968. He was also the president of the Chamber of Deputies from May 1955 until June 1963.

The Historic Compromise, also known as the Third Phase or the Democratic Alternative, was a historical political accommodation between Christian Democracy (DC) and the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in the 1970s.

Giuseppe Saragat was an Italian politician and statesman who served as the president of Italy from 1964 to 1971.

Giovanni Gronchi, was an Italian politician from Christian Democracy who served as the president of Italy from 1955 to 1962 and was marked by a controversial and failed attempt to bring about an "opening to the left" in Italian politics. He was reputed the real holder of the executive power in Italy from 1955 to 1962, behind the various Prime Ministers of this time.

A strategy of tension is a political policy wherein violent struggle is encouraged rather than suppressed. The purpose is to create a general feeling of insecurity in the population and make people seek security in a strong government.

Pietro Sandro Nenni was an Italian socialist politician and statesman, the national secretary of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) and senator for life since 1970. He was a recipient of the Lenin Peace Prize in 1951. He was one of the founders of the Italian Republic and a central figure of the Italian political left from the 1920s to the 1960s.

The 1968 Italian general election was held in Italy on 19 May 1968. The Christian Democracy (DC) remained stable around 38% of the votes. They were marked by a victory of the Communist Party (PCI) passing from 25% of 1963 to c. 30% at the Senate, where it presented jointly with the new Italian Socialist Party of Proletarian Unity (PSIUP), which included members of Socialist Party (PSI) which disagreed the latter's alliance with DC. PSIUP gained c. 4.5% at the Chamber. The Socialist Party and the Democratic Socialist Party (PSDI) presented together as the Unified PSI–PSDI, but gained c. 15%, far less than the sum of what the two parties had obtained separately in 1963.

The 1979 Italian general election was held in Italy on 3 June 1979. This election was called just a week before the European elections.

In Italy, the phrase Years of Lead refers to a period of political violence and social upheaval that lasted from the late 1960s until the late 1980s, marked by a wave of both far-left and far-right incidents of political terrorism and violent clashes.

Eugenio Scalfari was an Italian journalist. He was editor-in-chief of L'Espresso (1963–1968), a member of Parliament in Italy's Chamber of Deputies (1968–1972), and co-founder of La Repubblica and its editor-in-chief (1976–1996). He was known for his meetings and interviews with important figures, including Pope Francis, Enrico Berlinguer, Aldo Moro, Umberto Eco, Italo Calvino, and Roberto Benigni.

The Legislature III of Italy was the 3rd legislature of the Italian Republic, and lasted from 12 June 1958 until 15 May 1963. Its composition was the one resulting from the general election of 25 May 1958.

The Legislature IV of Italy was the 4th legislature of the Italian Republic, and lasted from 16 May 1963 until 4 June 1968. Its composition was the one resulting from the general election of 28 April 1963.

The Legislature VII of Italy was the 7th legislature of the Italian Republic, and lasted from 5 July 1976 until 19 June 1979. Its composition was the one resulting from the general election of 20 June 1976.

The kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro, also referred to in Italy as the Moro case, was a seminal event in Italian political history. On the morning of 16 March 1978, the day on which a new cabinet led by Giulio Andreotti was to have undergone a confidence vote in the Italian Parliament, the car of Aldo Moro, former prime minister and then president of the Christian Democracy party, was assaulted by a group of far-left terrorists known as the Red Brigades in via Fani in Rome. Firing automatic weapons, the terrorists killed Moro's bodyguards — two Carabinieri in Moro's car and three policemen in the following car — and kidnapped him. The events remain a national trauma. Ezio Mauro of La Repubblica described the events as Italy's 9/11. While Italy was not the sole European country to experience extremist terrorism, which also occurred in France, Germany, Ireland, and Spain, the murder of Moro was the apogee of Italy's Years of Lead.

In May 1978, Aldo Moro, a Christian Democracy (DC) statesman who advocated for a Historic Compromise with the Italian Communist Party, (PCI), was murdered after 55 days of captivity by the Red Brigades (BR), a far-left terrorist organization. Although the courts established that the BR had acted alone, conspiracy theories related to the Moro case persist. Much of the conspiracy theories allege additional involvement, from the Italian government itself, its secret services being involved with the BR, and the Propaganda Due (P2) to the CIA and Henry Kissinger, and Mossad and the KGB.

References

- ↑ Guzzanti, Paolo (22 January 2021). "Storia d'Italia, 1964: dalla morte di Togliatti al Piano Solo". Il Riformista (in Italian). Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ↑ Undercover lives : Soviet spies in the cities of the world. Helen Womack. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. 1998. ISBN 0-297-84126-2. OCLC 40877594.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Cento Bull, Italian Neofascism, p. 4

- ↑ Undercover lives : Soviet spies in the cities of the world. Helen Womack. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. 1998. ISBN 0-297-84126-2. OCLC 40877594.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "Twenty-Six Years Later, Details of Planned Rightist Coup Emerge". Associated Press. 5 January 1991.

- ↑ "Comic opera themes in Solo plot". Financial Times. 1 May 1991.