Rhodesia, officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979. During this fourteen year period Rhodesia served as the de facto successor state to the British colony of Southern Rhodesia, and in 1980 it became modern day Zimbabwe.

Ian Douglas Smith was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia from 1964 to 1979. He was the country's first leader to be born and raised in Rhodesia, and led the predominantly white government that unilaterally declared independence from the United Kingdom in November 1965 in opposition to the UK's demands for the implementation of majority rule as a condition for independence. His 15 years in power were defined by the country's international isolation and involvement in the Rhodesian Bush War, which pitted Rhodesia's armed forces against the Soviet- and Chinese-funded military wings of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU).

Zimbabwe Rhodesia, alternatively known as Republic of Zimbabwe Rhodesia, also informally known as Zimbabwe or Rhodesia, was a short-lived sovereign state that existed from 1 June 1979 to 18 April 1980, though lacked international recognition. Zimbabwe Rhodesia was preceded by another state named the Republic of Rhodesia and was briefly under a British-supervised transitional government sometimes referred to as a reestablished Southern Rhodesia, which according to British constitutional theory had remained the lawful government in the area after Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in 1965. About three months later, the re-established colony of Southern Rhodesia was granted internationally-recognized independence within the Commonwealth as the Republic of Zimbabwe.

Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) was a statement adopted by the Cabinet of Rhodesia on 11 November 1965, announcing that Rhodesia a British territory in southern Africa that had governed itself since 1923, now regarded itself as an independent sovereign state. The culmination of a protracted dispute between the British and Rhodesian governments regarding the terms under which the latter could become fully independent, it was the first unilateral break from the United Kingdom by one of its colonies since the United States Declaration of Independence in 1776. The UK, the Commonwealth, and the United Nations all deemed Rhodesia's UDI illegal, and economic sanctions, the first in the UN's history, were imposed on the breakaway colony. Amid near-complete international isolation, Rhodesia continued as an unrecognised state with the assistance of South Africa and Portugal.

The Rhodesian Front (RF) was a conservative political party in Southern Rhodesia, subsequently known as Rhodesia. Formed in March 1962 by white Rhodesians opposed to decolonisation and majority rule, it won that December's general election and subsequently spearheaded the country's Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) from the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1965, remaining the ruling party and upholding white minority rule through the majority of the Bush War until 1979. Initially led by Winston Field, the party was led by the majority of its existence by co-founder Ian Smith, who would later go following the end of the Bush War and the country's reconstitution as Zimbabwe, it dissolved in 1981 and was succeeded by the Republican Front.

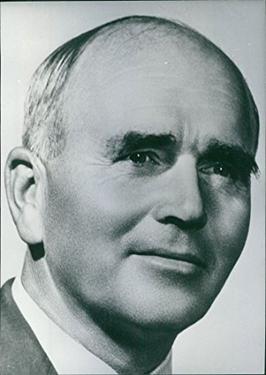

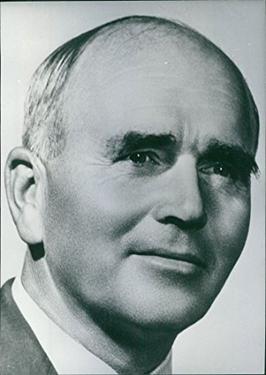

Sir Roland "Roy" Welensky was a Northern Rhodesian politician and the second and last Prime Minister of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

Elections in Southern Rhodesia were used from 1899 to 1923 to elect part of the Legislative Council and from 1924 to elect the whole of the Legislative Assembly which governed the colony. Since the granting of self-government in 1923, Southern Rhodesia used the Westminster parliamentary system as its basis of government. The Political party that had most of the seats in the Legislative Assembly became the government. The person in charge of this bloc was the Premier, later renamed Prime Minister, who then chose his cabinet from his elected colleagues.

General elections were held in Rhodesia on 30 July 1974. They saw the Rhodesian Front of Ian Smith re-elected, once more winning every one of the 50 seats elected by white voters.

General elections were held in Southern Rhodesia on 14 December 1962. Voters elected 65 members of the Legislative Assembly. The election was notable for bringing to power the Rhodesian Front, initially under Winston Field, which set the colony on the course for its eventual Unilateral Declaration of Independence.

Ahrn Palley was an independent politician in Rhodesia who criticised the Smith administration and the Unilateral Declaration of Independence. Ian Smith described him as "one of the most able politicians this country has produced, and although our political philosophies did not coincide, we always respected one another and maintained friendly relations."

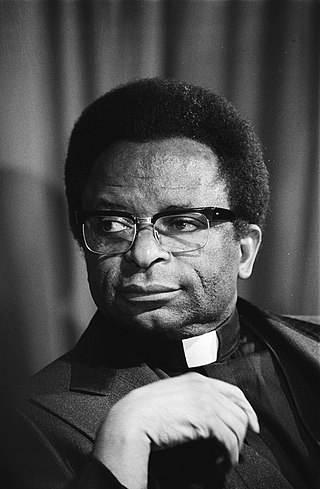

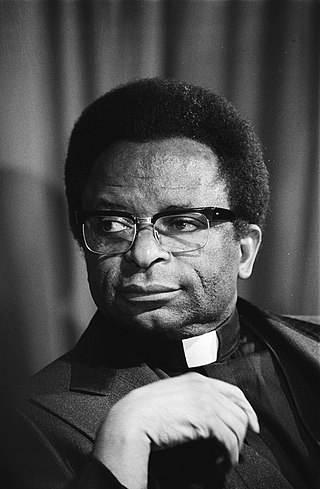

General elections were held in Rhodesia in April 1979, the first where the majority black population elected the majority of seats in parliament. The elections were held following the Internal Settlement negotiated by the Rhodesian Front government of Ian Smith and were intended to provide a peaceful transition to majority rule on terms not harmful to White Rhodesians. In accordance with the Internal Settlement, on 1 June, Rhodesia officially became the nation of Zimbabwe Rhodesia, under the government of the United African National Council elected in the 1979 elections. The Internal Settlement was not approved internationally but the incoming government under Bishop Abel Muzorewa did decide to participate in the Lancaster House talks which led to the end of the dispute and the creation of Zimbabwe.

General elections were held in Southern Rhodesia between 14 February and 4 March 1980 to elect the members of the House of Assembly of the first Parliament of the independent Zimbabwe. As stipulated by the new Constitution of Zimbabwe produced by the Lancaster House Conference, the new House of Assembly was to comprise 100 members, 80 of whom would be elected proportionally by province by all adult citizens on a common roll, and 20 of whom would be elected in single-member constituencies by whites on a separate roll.

The history of Rhodesia from 1965 to 1979 covers Rhodesia's time as a state unrecognised by the international community following the predominantly white minority government's Unilateral Declaration of Independence on 11 November 1965. Headed by Prime Minister Ian Smith, the Rhodesian Front remained in government until 1 June 1979, when the country was reconstituted as Zimbabwe Rhodesia.

A constitutional referendum was held in Southern Rhodesia, then a constituent territory of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, on 26 July 1961. The new constitution was approved by about 66% of those who voted; turnout was 77%.

The modern political history of Zimbabwe starts with the arrival of white people to what was dubbed Southern Rhodesia in the 1890s. The country was initially run by an administrator appointed by the British South Africa Company. The prime ministerial role was first created in October 1923, when the country achieved responsible government, with Sir Charles Coghlan as its first Premier. The third premier, George Mitchell, renamed the post prime minister in 1933.

William John Harper was a politician, general contractor and Royal Air Force fighter pilot who served as a Cabinet minister in Rhodesia from 1962 to 1968, and signed that country's Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) from Britain in 1965. Born into a prominent Anglo-Indian merchant family in Calcutta, Harper was educated in India and England and joined the RAF in 1937. He served as an officer throughout the Second World War and saw action as one of "The Few" in the Battle of Britain, during which he was wounded in action. Appalled by Britain's granting of independence to India in 1947, he emigrated to Rhodesia on retiring from the Air Force two years later.

Sir Thomas Hugh William Beadle, was a Rhodesian lawyer, politician and judge who served as Chief Justice of Southern Rhodesia from March 1961 to November 1965, and as Chief Justice of Rhodesia from November 1965 until April 1977. He came to international prominence against the backdrop of Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) from Britain in November 1965, upon which he initially stood by the British Governor Sir Humphrey Gibbs as an adviser; he then provoked acrimony in British government circles by declaring Ian Smith's post-UDI administration legal in 1968.

Richard Brathwaite Hope Hall ICD was a British-born merchant banker, businessman, and politician active in Rhodesia during the 1960s and 70s. A member of Prime Minister Ian Smith's UDI cabinet, he served as a member of parliament in Rhodesia's House of Assembly from 1965 to 1976. He began his political career as a member of the Dominion Party, and served as its chairman from 1960 to 1962. In 1962, he was a founding member of the Rhodesian Front, but switched to the Rhodesian Action Party in 1976. After unsuccessfully running for re-election in 1977, he moved back to the United Kingdom, where he lived until his death.

Lancelot Bales Smith, was an English-born Rhodesian farmer and politician. Elected to Parliament in the 1950s, he was a founding member of Rhodesian Front in 1962. He was Minister without portfolio in the cabinet of Prime Minister Ian Smith at the time of Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965. In 1968, after serving as Deputy Minister of Agriculture, he was appointed Minister of Internal Affairs, a position he held until 1974, when he exited politics.

Rhodesia, was a self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa. Until 1964, the territory was known as Southern Rhodesia, and less than a year before the name change the colony formed a part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland and hosted its capital city, Salisbury. On 1 January 1964, the three parts of the Federation became separate colonies as they had been before the founding of the Federation on 1 August 1953. The demise of the short-lived union was seen as stemming overwhelmingly from black nationalist movements in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, and both colonies were fast-tracked towards independence - Nyasaland first, as Malawi, on 6 July 1964 and Northern Rhodesia second, as Zambia, on 24 October. Southern Rhodesia, by contrast, stood firmly under white government, and its white population, which was far larger than the white populations elsewhere in the erstwhile Federation, was, in general, strongly opposed to the introduction of black majority rule. The Southern Rhodesian prime minister, Winston Field, whose government had won most of the federation's military and other assets for Southern Rhodesia, began to seek independence from the United Kingdom without introducing majority rule. However, he was unsuccessful and his own party, the Rhodesian Front, forced him to resign. Days prior to his resignation, on Field's request, Southern Rhodesia had changed its flag to a sky blue ensign defaced with the Rhodesian coat of arms, becoming the first British colony to use a sky blue ensign instead of a dark blue one.