| Lake zones |

|---|

| Lake stratification |

| Lake types |

| See also |

Polymictic lakes are holomictic lakes that are too shallow to develop thermal stratification; thus, their waters can mix from top to bottom throughout the ice-free period. Polymictic lakes can be divided into cold polymictic lakes (i.e., those that are ice-covered in winter), and warm polymictic lakes (i.e., polymictic lakes in regions where ice-cover does not develop in winter). [1] While such lakes are well-mixed on average, during low-wind periods, weak and ephemeral stratification can often develop. [2] [3]

Limnology is the study of inland aquatic ecosystems. The study of limnology includes aspects of the biological, chemical, physical, and geological characteristics of fresh and saline, natural and man-made bodies of water. This includes the study of lakes, reservoirs, ponds, rivers, springs, streams, wetlands, and groundwater. Water systems are often categorized as either running (lotic) or standing (lentic).

The hypolimnion or under lake is the dense, bottom layer of water in a thermally-stratified lake. The word "hypolimnion" is derived from Ancient Greek: λιμνίον, romanized: limníon, lit. 'lake'. It is the layer that lies below the thermocline.

The epilimnion or surface layer is the top-most layer in a thermally stratified lake.

A thermocline is a distinct layer based on temperature within a large body of fluid with a high gradient of distinct temperature differences associated with depth. In the ocean, the thermocline divides the upper mixed layer from the calm deep water below.

A meromictic lake is a lake which has layers of water that do not intermix. In ordinary, holomictic lakes, at least once each year, there is a physical mixing of the surface and the deep waters.

Lake stratification is the tendency of lakes to form separate and distinct thermal layers during warm weather. Typically stratified lakes show three distinct layers: the epilimnion, comprising the top warm layer; the thermocline, the middle layer, whose depth may change throughout the day; and the colder hypolimnion, extending to the floor of the lake.

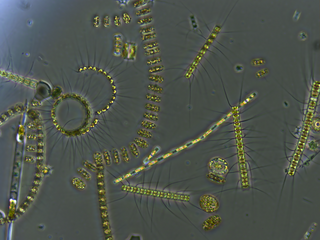

In biological oceanography, critical depth is defined as a hypothetical surface mixing depth where phytoplankton growth is precisely matched by losses of phytoplankton biomass within the depth interval. This concept is useful for understanding the initiation of phytoplankton blooms.

A dimictic lake is a body of freshwater whose difference in temperature between surface and bottom layers becomes negligible twice per year, allowing all strata of the lake's water to circulate vertically. All dimictic lakes are also considered holomictic, a category which includes all lakes which mix one or more times per year. During winter, dimictic lakes are covered by a layer of ice, creating a cold layer at the surface, a slightly warmer layer beneath the ice, and a still-warmer unfrozen bottom layer, while during summer, the same temperature-derived density differences separate the warm surface waters, from the colder bottom waters. In the spring and fall, these temperature differences briefly disappear, and the body of water overturns and circulates from top to bottom. Such lakes are common in mid-latitude regions with temperate climates.

Monomictic lakes are holomictic lakes that mix from top to bottom during one mixing period each year. Monomictic lakes may be subdivided into cold and warm types.

Amictic lakes are "perennially sealed off by ice, from most of the annual seasonal variations in temperature." Amictic lakes exhibit inverse cold water stratification whereby water temperature increases with depth below the ice surface 0 °C (less-dense) up to a theoretical maximum of 4 °C.

Holomictic lakes are lakes that have a uniform temperature and density from surface to bottom at a specific time during the year, which allows the lake waters to mix in the absence of stratification.

A chemocline is a type of cline, a layer of fluid with different properties, characterized by a strong, vertical chemistry gradient within a body of water. In bodies of water where chemoclines occur, the cline separates the upper and lower layers, resulting in different properties for those layers. The lower layer shows a change in the concentration of dissolved gases and solids compared to the upper layer.

The Trophic State Index (TSI) is a classification system designed to rate water bodies based on the amount of biological productivity they sustain. Although the term "trophic index" is commonly applied to lakes, any surface water body may be indexed.

The deep chlorophyll maximum (DCM), also called the subsurface chlorophyll maximum, is the region below the surface of water with the maximum concentration of chlorophyll. The DCM generally exists at the same depth as the nutricline, the region of the ocean where the greatest change in the nutrient concentration occurs with depth.

A lake is a naturally occurring, relatively large body of water localized in a basin or interconnected basins surrounded by dry land. Lakes lie completely on land and are separate from the ocean, although, like the much larger oceans, they form part of the Earth's water cycle by serving as large standing pools of storage water. Most lakes are freshwater and account for almost all the world's surface freshwater, but some are salt lakes with salinities even higher than that of seawater.

A thermal bar is a hydrodynamic feature that forms around the edges of holomictic lakes during the seasonal transition to stratified conditions, due to the shorter amount of time required for shallow areas of the lake to stratify.

Lake metabolism represents a lake's balance between carbon fixation and biological carbon oxidation. Whole-lake metabolism includes the carbon fixation and oxidation from all organism within the lake, from bacteria to fishes, and is typically estimated by measuring changes in dissolved oxygen or carbon dioxide throughout the day.

Stratification in water is the formation in a body of water of relatively distinct and stable layers by density. It occurs in all water bodies where there is stable density variation with depth. Stratification is a barrier to the vertical mixing of water, which affects the exchange of heat, carbon, oxygen and nutrients. Wind-driven upwelling and downwelling of open water can induce mixing of different layers through the stratification, and force the rise of denser cold, nutrient-rich, or saline water and the sinking of lighter warm or fresher water, respectively. Layers are based on water density: denser water remains below less dense water in stable stratification in the absence of forced mixing.

Lake Lacawac is located at the very middle of Lacawac's Sanctuary Field Station in Pennsylvania and has been deemed the "southernmost unpolluted glacial lake in North America." Lake Lacawac has proven to be invaluable to researchers and students to conduct field experiments in order to learn more about the limnology of the lake.

An alpine lake is a high-altitude lake in a mountainous area, usually near or above the tree line, with extended periods of ice cover. These lakes are commonly glacial lakes formed from glacial activity but can also be formed from geological processes such as volcanic activity or landslides. Many alpine lakes that are fed from glacial meltwater have the characteristic bright turquoise green color as a result of glacial flour, suspended minerals derived from a glacier scouring the bedrock. When active glaciers are not supplying water to the lake, such as a majority of Rocky Mountains alpine lakes in the United States, the lakes may still be bright blue due to the lack of algal growth resulting from cold temperatures, lack of nutrient run-off from surrounding land, and lack of sediment input. The coloration and mountain locations of alpine lakes attract lots of recreational activity.