Related Research Articles

A day is the time period of a full rotation of the Earth with respect to the Sun. On average, this is 24 hours. As a day passes at a given location it experiences morning, noon, afternoon, evening, and night. This daily cycle drives circadian rhythms in many organisms, which are vital to many life processes.

An hour is a unit of time historically reckoned as 1⁄24 of a day and defined contemporarily as exactly 3,600 seconds (SI). There are 60 minutes in an hour, and 24 hours in a day.

Kali Yuga, in Hinduism, is the fourth and worst of the four yugas in a Yuga Cycle, preceded by Dvapara Yuga and followed by the next cycle's Krita (Satya) Yuga. It is believed to be the present age, which is full of conflict and sin.

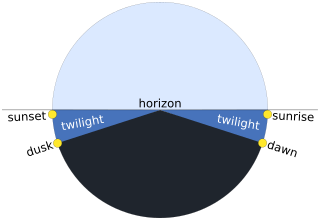

Dawn is the time that marks the beginning of twilight before sunrise. It is recognized by the appearance of indirect sunlight being scattered in Earth's atmosphere, when the centre of the Sun's disc has reached 18° below the observer's horizon. This morning twilight period will last until sunrise, when direct sunlight outshines the diffused light.

Muhūrta is a Hindu unit of measurement for time along with nimiṣa, kāṣṭhā, and kalā in the Hindu calendar.

Twilight is light produced by sunlight scattering in the upper atmosphere, when the Sun is below the horizon, which illuminates the lower atmosphere and the Earth's surface. The word twilight can also refer to the periods of time when this illumination occurs.

In modern usage, civil time refers to statutory time as designated by civilian authorities. Modern civil time is generally national standard time in a time zone at a fixed offset from Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), possibly adjusted by daylight saving time during part of the year. UTC is calculated by reference to atomic clocks and was adopted in 1972. Older systems use telescope observations.

Samaya or Samayam is a Sanskrit term referring to the "appointed or proper time, [the] right moment for doing anything." In Indian languages, samayam, or samay in Indo-Aryan languages, is a unit of time.

Sandhyavandanam is a mandatory religious ritual centring around the recitation of the Gayatri mantra, traditionally supposed to be performed three times a day by Dvija communities of Hindus, particularly those initiated through the sacred thread ceremony referred to as the Upanayanam and instructed in its execution by a Guru, in this case one qualified to teach Vedic ritual. Sandhyopasana is considered as a path to attain salvation (moksha).

In Hindu astrology, Rāhukāla or Rahukālam is an inauspicious period of the day, not considered favourable to start any good deed. The Rāhukāla spans for approximately 90 minutes every day between sunrise and sunset.

Zmanim are specific times of the day in Jewish law.

Hindu units of time are described in Hindu texts ranging from microseconds to trillions of years, including cycles of cosmic time that repeat general events in Hindu cosmology. Time is described as eternal. Various fragments of time are described in the Vedas, Manusmriti, Bhagavata Purana, Vishnu Purana, Mahabharata, Surya Siddhanta etc.

Vaishnava calendar

Brahmamuhurta is a 48-minute period (muhurta) that begins one hour and 36 minutes before sunrise, and ends 48 minutes before sunrise. It is traditionally the penultimate phase or muhurta of the night, and is considered an auspicious time for all practices of yoga and most appropriate for meditation, worship or any other religious practice. Spiritual activities performed early in the morning are said to have a greater effect than in any other part of the day.

Choghadiya refers to an auspicious period of twenty-four minutes in Indian astrology.

Pahar, which is more commonly pronounced peher is a traditional unit of time used in India, Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh. One pahar nominally equals three hours, and there are eight pahars in a day. In India, the measure is primarily used in North India and hindi speaking communities throughout the Deccan in Southern India.

In Roman timekeeping, a day was divided into periods according to the available technology. Initially, the day was divided into two parts: the ante meridiem and the post meridiem. With the advent of the sundial circa 263 BC, the period of the natural day from sunrise to sunset was divided into twelve hours.

In Jyotiṣa or Indian astrology, the term Upagrāha refers to the so-called "shadow planets" that are actually mathematical points, that are used for astrological evaluation. Upagrāha is a generic term used for two distinct and different calculations. One type of Upagrāha called Aprakāśa (अप्रकाश) is calculated from the degree of the Sun. Another type is more generally called Upagrāha or Kālavelā (कालवेला) is calculated by dividing duration of diurnal sky or the duration of the nocturnal sky into eight parts. The classic writers like Parāśara, Varāhamihira and later writers like Vankatesa Śarma, author of Sarvartha Chintamani, all classify the Upagrāhas in various ways.

Relative hour, sometimes called halachic hour, seasonal hour and variable hour, is a term used in rabbinic Jewish law that assigns 12 hours to each day and 12 hours to each night, all throughout the year. A relative hour has no fixed length in absolute time, but changes with the length of daylight each day - depending on summer, and in winter. Even so, in all seasons a day is always divided into 12 hours, and a night is always divided into 12 hours, which invariably makes for a longer hour or a shorter hour. At Mediterranean latitude, one hour can be about 45 minutes at the winter solstice, and 75 minutes at summer solstice. All of the hours mentioned by the Sages in either the Mishnah or Talmud, or in other rabbinic writings, refer strictly to relative hours.

A Yuga Cycle is a cyclic age (epoch) in Hindu cosmology. Each cycle lasts for 4,320,000 years and repeats four yugas : Krita (Satya) Yuga, Treta Yuga, Dvapara Yuga, and Kali Yuga.

References

- ↑ Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary, sv. "prahara."

- ↑ Bhagavata Purana (also known as Srimad Bhagavatam) 3.11.10 Archived 2010-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Indic astronomical calculations identify the brahma-muhurta as the penultimate muhurta before dawn (in other words, the first of two muhurtas, or periods of 48 minutes, before dawn). If sunrise is at 6 am, the brahma-muhurta starts 96 minutes earlier, at 4:24 am. (The traditional calculations are available through GCal, computer software developed by the ISKCON GBC for the purposes of calculating the Vaishnava calendar, now available online and as iTunes app). See also Āgama-kosha, vol 4, by Saligrama Krishna, Ramachandra Rao, Rama R. Rao, Kalpatharu Research Academy, 1991. Other secondary sources speak of the brahma-muhurta as the antepenultimate muhurta before dawn (in other words, the first of three muhurtas before dawn). Assuming a 6 am sunrise, this would place the start of the brahma-muhurta at 3:36 am; see Gaya Charan Tripathi, "Communication with God: The Daily Puja Ceremony in the Jagannatha Temple" and Times of India. Yet other sources conflate the two accounts: they claim that the "brahma-muhurta" begins two muhurtas before dawn (i.e., 4:24), but say that it begins at 3:36 am (which would be three muhurtas before dawn); see the ISKCON program for morning sadhana. The precession of the equinoxes may complicate things yet further; see e.g. the discussion of Muhurta: yearly calibration.

- ↑ Some scholars correctly infer that in seasons (and regions) where days and nights are unequal in length, the praharas expand and contract in length. See Duncan Forbes' early comment on the pahar (= prahar) in Northern India: "The first pahar of the day began at sunrise, and of the night at sunset; and since the time from sunrise to noon made exactly two pahars, it follows that in the north of India the pahar must have varied from three and a-half hours about the summer solstice, to two and a-half in winter, the pahars of the night varying inversely." (Duncan Forbes, LL.D, transl. Bāgh O Bahār; or Tales of the Four Derwishes, by Mīr Amman of Dihli. London: W. H. Allen & Co. 1882, (p. 23, note 1). What we are encountering here is a difference between modern cultures that rely on clock time, and traditional cultures where the length of a day is observed in the sky, from sunset to sundown.

- ↑ Walter Kaufmann, The Ragas of North India, Calcutta: Oxford (1968)

- ↑ For Bhatkande's assignation of ragas to praharas, see Anthony Peter Westbrook, "Testing the Time Theory," Hinduism Today, February 2000. But note, contrary to Westbrook's assertion, that the concept of praharas existed long before Bhatkande made use of them in the 19th century; see, for example, the numerous references in the 16th century scripture Caitanya Caritamrta.

- ↑ Henry M. Hoenigswald, Spoken Hindustani, vol. 2, p. 403. Henry Holt (1945)