Yogachara is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through the interior lens of meditation as well as philosophical reasoning (hetuvidyā). Yogachara was one of the two most influential traditions of Mahayana Buddhism in India, along with Madhyamaka.

In Buddhist philosophy, Buddha-nature is the potential for all sentient beings to become a Buddha or the fact that all beings already have a pure buddha-essence within. "Buddha-nature" is the common English translation for several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, most notably tathāgatagarbha and buddhadhātu, but also sugatagarbha, and buddhagarbha. Tathāgatagarbha can mean "the womb" or "embryo" (garbha) of the "thus-gone one" (tathāgata), and can also mean "containing a tathāgata". Buddhadhātu can mean "buddha-element," "buddha-realm" or "buddha-substrate".

Abhinavagupta was a philosopher, mystic and aesthetician from Kashmir. He was also considered an influential musician, poet, dramatist, exegete, theologian, and logician – a polymathic personality who exercised strong influences on Indian culture.

Swami Lakshman Joo, born Lakshman Raina and also called Lal Sahib by his followers, was a mystic and scholar of Kashmir Shaivism.

Vasugupta was the author of the Shiva Sutras, an important text of the Advaita tradition of Kashmir Shaivism, also called Trika.

Somananda was one of the teachers of Kashmir Shaivism, in the lineage of Trayambaka, author of the first philosophical treatise of this school, Śivadṛṣṭi. A contemporary of Bhaṭṭa Kallaṭa, the two formed the first wave of Kashmiri Shaivites to propose in a rigorous and logical way the concepts of nondual Shaivism. Somananda lived in Kashmir, most probably in Srinagar, where most of the later philosophers of the school lived, as a householder.

Kashmir Shaivism or Trika Shaivism, is a nondualist Hindu tradition of Shaiva-Shakta Tantra which originated in Kashmir sometime after 850 CE. Since this tradition originated in Kashmir it is often called "Kashmiri Shaivism". It later went on to become a pan-Indian movement termed "Trika" by its great exegete, Abhinavagupta, and particularly flourished in Odisha and Maharashtra. Defining features of the Trika tradition are its idealistic and monistic Pratyabhijna ("Recognition") philosophical system, propounded by Utpaladeva and Abhinavagupta, and the centrality of the three goddesses Parā, Parāparā, and Aparā.

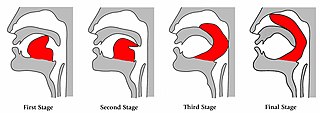

Khecarī mudrā is a hatha yoga practice carried out by curling the tip of the tongue back into the mouth until it reaches above the soft palate and into the nasal cavity. The tongue is made long enough to do this with many months of daily tongue stretching and, in some versions of the practice, by gradually severing the lingual frenulum with a sharp implement over a period of months.

Svātantrya is the Kashmiri Shaivite concept of divine sovereignty. Svātantrya is described as an energy that emanates from the Supreme (Paramaśiva), a wave of motion inside consciousness (spanda) that acts as the fundament of the world, or in another view, the original word. It does not use any external instrument as it itself is the first stage of creation.

Shiva Sutras are a collection of seventy seven aphorisms that form the foundation of the tradition of spiritual mysticism known as Kashmir Shaivism. They are attributed to the sage Vasugupta of the 9th century C.E.

The tattvas in Indian philosophy are elements or principles of reality. Tattvas are the basic concepts to understand the nature of absolute, the souls and the universe in Samkhya and Shaivite philosophies. Samkhya philosophy lists 25 tattvas while later Shaivite philosophies extend the number to 36.

Tantrāloka is a treatise of Abhinavagupta, a writer and philosopher of the Kashmir Shaivism school of Hindu philosophy.

In the Hindu religious traditions of Shaktism and Shaivism, Kaula, also known as Kula, and, is a Tantric tradition which is characterised by distinctive rituals and symbolism connected with the worship of Shakti and Shiva that is associated with cremation-ground or charnel ground asceticism.

The Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra is a Shiva Tantra, of the Kaula Trika tradition of Kashmir Shaivism, possibly authored by Guru Keyūravatī. Singh notes that it is difficult to establish an exact date for the text, and it could have been written at some time from the 7th to the 8th century CE. It is also called the Śiva-jñāna-upaniṣad by Abhinavagupta.

Pratyabhijñā or Pratyabhigyā is an idealistic, monistic, and theistic school of philosophy in Kashmir Shaivism which originated in the ninth century CE. The term Trika was used by Abhinavagupta to represent the whole of Kashmir Shaivism, or to designate the Pratyabhijñā system.

Jaideva Singh was an Indian musicologist and philosopher. He played a key role in the development of All India Radio where he was chief producer. He was influenced by the Indian musicologist Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande.

Ratnākaraśānti was an influential Buddhist philosopher and vajrayana tantric adept and scholar. He was the "gate scholar" of Vikramaśilā university's eastern gate, a key post in the university's leadership. Ratnākara was known by the title kalikālasarvajña and is depicted as one of the eighty-four mahāsiddhas.

Ratnakīrti was an Indian Buddhist philosopher of the Yogācāra and epistemological (pramāṇavāda) schools who wrote on logic, philosophy of mind and epistemology. Ratnakīrti studied at the Vikramaśīla monastery in modern-day Bihar. He was a pupil of Jñānaśrīmitra, and Ratnakīrti refers to Jñānaśrīmitra in his work as his guru with phrases such as yad āhur guravaḥ.

Jñānaśrīmitra was an Indian Buddhist philosopher of the epistemological (pramana) tradition of Buddhist philosophy, which goes back to Dignāga and Dharmakīrti. Jñānaśrīmitra was also known as a Yogācāra Buddhist who defended a form of Buddhist idealism termed Sākāravada which holds that cognitive content or aspects of consciousness ("ākāras") are real and not illusory.

Mark S. G. Dyczkowski is an English Indologist, musician, and scholar of Tantra and Kashmir Shaivism. He has published multiple translations and commentaries, most notably the 12-volume Manthanabhairava Tantra and an 11-volume Tantrāloka including the commentary by Jayaratha. Dyczkowski also plays the sitar and has collected over 1,500 compositions for sitar.