Jürgen Habermas is a German philosopher and social theorist in the tradition of critical theory and pragmatism. His work addresses communicative rationality and the public sphere.

Rational choice theory refers to a set of guidelines that help understand economic and social behaviour. The theory originated in the eighteenth century and can be traced back to the political economist and philosopher Adam Smith. The theory postulates that an individual will perform a cost–benefit analysis to determine whether an option is right for them. Rational choice theory looks at three concepts: rational actors, self interest and the invisible hand.

Thomas Crombie Schelling was an American economist and professor of foreign policy, national security, nuclear strategy, and arms control at the School of Public Policy at University of Maryland, College Park. He was also co-faculty at the New England Complex Systems Institute.

Deterrence theory refers to the scholarship and practice of how threats of using force by one party can convince another party to refrain from initiating some other course of action. The topic gained increased prominence as a military strategy during the Cold War with regard to the use of nuclear weapons and is related to but distinct from the concept of mutual assured destruction, according to which a full-scale nuclear attack on a power with second-strike capability would devastate both parties. The central problem of deterrence revolves around how to credibly threaten military action or nuclear punishment on the adversary despite its costs to the deterrer. Deterrence in an international relations context is the application of deterrence theory to avoid conflict.

In economics, dynamic inconsistency or time inconsistency is a situation in which a decision-maker's preferences change over time in such a way that a preference can become inconsistent at another point in time. This can be thought of as there being many different "selves" within decision makers, with each "self" representing the decision-maker at a different point in time; the inconsistency occurs when not all preferences are aligned.

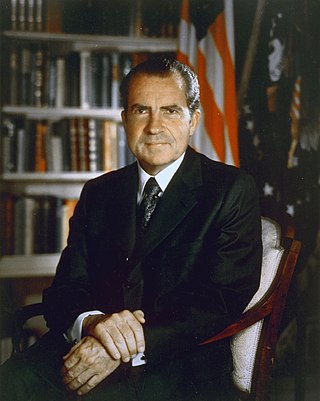

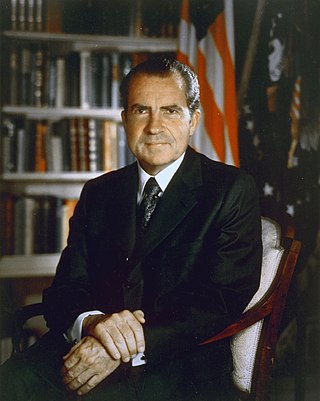

The madman theory is a political theory commonly associated with the foreign policy of U.S. President Richard Nixon and his administration, who tried to make the leaders of hostile Communist Bloc nations think Nixon was irrational and volatile so that they would avoid provoking the U.S. in fear of an unpredictable response.

Jon Elster is a Norwegian philosopher and political theorist who holds the Robert K. Merton professorship of Social Science at Columbia University.

Rational egoism is the principle that an action is rational if and only if it maximizes one's self-interest. As such, it is considered a normative form of egoism, though historically has been associated with both positive and normative forms. In its strong form, rational egoism holds that to not pursue one's own interest is unequivocally irrational. Its weaker form, however, holds that while it is rational to pursue self-interest, failing to pursue self-interest is not always irrational.

A Ulysses pact or Ulysses contract is a freely made decision that is designed and intended to bind oneself in the future. The term is used in medicine, especially in reference to advance directives, where there is some controversy over whether a decision made by a person in one state of health should be considered binding upon that person when they are in a markedly different, usually worse, state of health.

James D. Fearon is the Theodore and Francis Geballe Professor of Political Science at Stanford University; he is known for his work on the theory of civil wars, international bargaining, war's inefficiency puzzle, audience costs, and ethnic constructivism. According to a 2011 survey of International Relations scholars, Fearon is among the most influential International Relations scholars of the last twenty years. His 1995 article "Rationalist Explanations for War" is the most assigned journal article in International Relations graduate training at U.S. universities.

Egonomics is the idea that "within each individual exists two selves: the past or future self and the present self, constantly at odds, leading to a sort of cognitive dissonance between the two. Both selves exist within us and are equally valid, but aren’t always active at the same time. It’s a natural and ongoing conflict between immediate desire and long-term desires, we call longing." Egonomics is the pursuit of awareness of that longing.

A non-credible threat is a term used in game theory and economics to describe a threat in a sequential game that a rational player would not actually carry out, because it would not be in his best interest to do so.

Diego Gambetta is an Italian-born social scientist. He is a Carlo Alberto Chair at the Collegio Carlo Alberto in Turin. He is well known for his vivid and unconventional applications of economic theory and a rational choice theory approach to understanding a variety of social phenomena. He has made important analytical contributions to the concept of trust by using game theory and signalling theory.

In economics, and in other social sciences, preference refers to an order by which an agent, while in search of an "optimal choice", ranks alternatives based on their respective utility. Preferences are evaluations that concern matters of value, in relation to practical reasoning. Individual preferences are determined by taste, need, ..., as opposed to price, availability or personal income. Classical economics assumes that people act in their best (rational) interest. In this context, rationality would dictate that, when given a choice, an individual will select an option that maximizes their self-interest. But preferences are not always transitive, both because real humans are far from always being rational and because in some situations preferences can form cycles, in which case there exists no well-defined optimal choice. An example of this is Efron dice.

A commitment device is, according to journalist Stephen J. Dubner and economist Steven Levitt, a way to lock oneself into following a plan of action that one might not want to do, but which one knows is good for oneself. In other words, a commitment device is a way to give oneself a reward or punishment to make what might otherwise become an empty promise stronger and believable.

Strategic delegation refers to delegation of decision-making to agents, and accompanying organizational design choices, which, under strategic interdependence, serve as commitments that influence interactions with rivals and potentially lead to beneficial outcomes for the delegating party.

Analytical Marxism is an academic school of Marxist theory which emerged in the late 1970s, largely prompted by G. A. Cohen's Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence (1978). In this book, Cohen drew on the Anglo–American tradition of analytic philosophy in an attempt to raise the standards of clarity and rigor within Marxist theory, which led to his distancing of Marxism from continental European philosophy. Analytical Marxism rejects much of the Hegelian and dialectical tradition associated with Marx's thought.

Compellence is a form of coercion that attempts to get an actor to change its behavior through threats to use force or the actual use of limited force. Compellence can be more clearly described as "a political-diplomatic strategy that aims to influence an adversary's will or incentive structure. It is a strategy that combines threats of force, and, if necessary, the limited and selective use of force in discrete and controlled increments, in a bargaining strategy that includes positive inducements. The aim is to induce an adversary to comply with one's demands, or to negotiate the most favorable compromise possible, while simultaneously managing the crisis to prevent unwanted military escalation."

Ulysses and the Sirens is a 1909 oil painting by Herbert James Draper measuring 69.25 in × 84 in. It is held at the Ferens Art Gallery in Kingston upon Hull, England. The gallery purchased the painting from Draper in 1910 for £600. Draper also painted a reduced replica that is housed at the Leeds Art Gallery. The subject of the painting is an episode in the epic poem Odyssey by Homer in which Ulysses is tormented by the voices of Sirens, although there are only two Sirens in Homer's poem and they stay in a meadow. The painting depicts Ulysses tied to the mast and forcibly attendant to the Sirens' seductions. Although the Sirens were depicted in ancient Greek art as scary, ugly creatures, Draper maintains the spirit but not the content of the story by transferring the Sirens' seductiveness from their song to a visible form, depicting the Sirens as beautiful mermaids who invade Ulysses' ship. The Sirens are nude or nearly so and their tails disappear as they board the ship. Draper's conflation of Sirens with mermaids and his sexualization of these figures are consistent with other artwork of the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Norwegian social theorist Jon Elster used the name of Draper's painting as the title for his 1979 book about rationality and precommitment.

Rational choice is a prominent framework in international relations scholarship. Rational choice is not a substantive theory of international politics, but rather a methodological approach that focuses on certain types of social explanation for phenomena. In that sense, it is similar to constructivism, and differs from liberalism and realism, which are substantive theories of world politics. Rationalist analyses have been used to substantiate realist theories, as well as liberal theories of international relations.