Summary

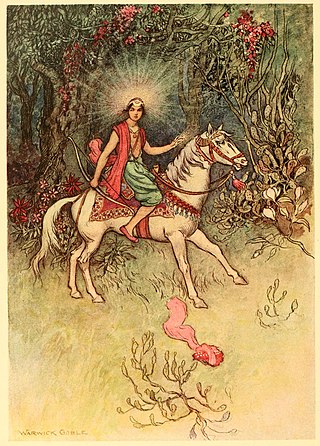

A poor Brahman and his wife live in such a state of poverty, they resort to gathering roots and herbs to eat. One day, the Brahman finds an eggplant and brings it home to plant. He and his wife water it and it yields a large, purple fruit. The Brahman's wife takes a knife to cut open the large eggplant in the garden. When she stabs the large fruit, a low moan is heard. The wife stabs it again and a voice inside it the eggplant begs for the woman to be careful. The wife opens the eggplant and finds a little maiden inside, dressed in white and purple garments. The Brahman and his wife decide to adopt the girl as their daughter and name her Princess Aubergine.

Next to the Brahman's hut, a king lives with his queen and seven sons. One day, a slave-girl from the palace goes to the Brahman's hut to ask for some light, and sees Princess Aubergine. So lovely is she, that the slave-girl rushes back to the palace to tell the queen about her. The queen, despite being beautiful herself, is told that the Brahman's daughter is even more beautiful than her, and fears the king will replace her.

So the queen devises a plan: she invites Princess Aubergine to the palace, and convinces the girl to live there with her as the queen's sister. Time passes, and the Queen, adept in the arts of magic, learns through her powers that the Princess Aubergine is a fairy, and, while the maiden is asleep, casts spells on her to reveal the location of her lifeforce. The Princess murmurs that her lifeforce is in the queen's first son; by killing him, the queen will kill Aubergine.

The queen kills her firstborn son, and sends the servant-girl to check on Princess Aubergine, who is still alive. Failing her first attempt to kill the maiden, the queen goes back to enchanting the girl for her to disclose her secret. The princess keeps telling that her lifeforce lies in each of the queen's other sons, which are killed every time.

After all her sons have been killed, the queen, fueled with rage, manages to enchant Aubergine with even more powerful spells for her to reveal the location of her lifeforce: in a nine-lakh necklace, inside a tiny box, inside a bumblebee, inside a red and green fish that lives in a river somewhere far away.

The queen convinces her husband, the king, to procure her the nine-lakh necklace, like some sort of comfort due to the sudden loss of their sons, who, according to the queen, have died of a "mysterious illness". The king brings back the fish and the queen finds the fabled necklace. Meanwhile, Princess Aubergine, sensing her approaching death, goes back to her adoptive parents' hut and tells the Brahman to prepare her resting place: they must not bury her, but set her on her bed, deep in the wilderness, surround it with flowers, and build a mudwall around it.

The Brahman and his wife follow her instructions, and the queen's slave-girl reports back that Aubergine is not buried, by lies out in the open. The queen contents herself with this small victory, since she still has the necklace.

One day, the king decides to go on a hunt to occupy his mind off the loss of his seven sons, but the queen warns him against hunting in the north. The king hunts in the east, in the west, and in the south, and, out of options, begins to hunt in the north. The king sees the mudwall and the bed of flowers that surround Princess Aubergine's body. The king becomes entranced by her beauty and begins a long, secret vigil on her body. After a year, a son appears next to the maiden's body, and, some time later, the boy tells the king his mother, the maiden, comes alive at night to care for him, and dies in the morning.

The king then asks the boy about his origins, and the boy answers that he is the king's son and Aubergine's, sent to console him after the death of the king's seven sons by the hands of the queen. The boy also reveals that Aubergine can be revived by retrieving the nine-lakh necklace around the queen's neck, but he is the only one that can get it.

The king brings the boy with him to the palace. The queen, seeing the boy, tries to give him poisoned food, but the boy refuses to touch the food until the queen gives him the necklace to play. The queen, wanting to see the boy eat the food, gives him the necklace, and he hurries back to his mother Aubergine to revive her.

Upon placing the necklace on his mother, Princess Aubergine awakens. The king goes to her and talks her into coming to the palace with him and becoming his bride, but Aubergine refuses, until the king digs up a ditch, fills it with snakes and scorpions, and throws the queen inside it. The king orders some servants to fulfill her orders, then tells the king to come see something with him. Despite refusing, the queen is seized by the guards, tied up, thrown in the ditch and buried alive. Princess Aubergine and her son come to live in the palace with the king. [3] [4] [5]

Variants

India

Richard C. Temple noted that the tale "abound[ed] in various forms in the Pânjâb". [2] In the second revision of the index, published in 1961, Stith Thompson located 7 variants in India. [6]

In an Indian tale titled Princess Brinjal, a poor gardener asks a Koiri for alms, and is given a brinjal. The gardener's goes home, places the brinjal in a pot and cooks it. A rattle inside the pot draws the gardener's attention and he opens the pot to see a fairy (peri) and a "heavenly mansion" inside it. The princess introduces herself as "Princess Brinjal" and turns the gardener's poor hut in a grand palace, and they live together. Some time later, a Anir's wife goes to the Princess Brinjal and gives her some milk and curds, and is paid with a pearl. She goes to the Rája's palace to sell milk and curds, and is given wheat husks. She comments to a gatekeeper about Princess Brinjal's generosity, and the gatekeeper tells the Ráni about it. The Ráni fears her husband might want Brinjal as his new wife and decides to poison her. She goes to Brinjal's palace, who invites her in, despite knowing her plan. The Ráni, in turn, invites Brinjal to her palace, but she asks for the Ráni to pave a road between their palaces and decorate it with curtains, so that no man can see her. Princess Brinjal goes to the Ráni's palace. The Ráni tries to poison the princess with the food, but the princess declines to eat any dish. However, goaded by the Ráni, the princess tells her about a ruby necklace inside a box, located on the branches of a pipal tree. After the princess leaves, the Ráni asks her husband to get the necklace. He does and Princess Brinjal falls dead. Before she dies, she asks the gardener to build a tomb and lay her there. Time passes, and the Rája visits Brinjal's resting place. He drinks some water and eats half of a pomegranate. The same night, Brinjal awakens and eats the other half. She and the Rája fall in love and have a son. Brinjal tells the Ráj about the necklace; he takes it back from the Ráni and executes her, making Brinjal his new queen. [12] The tale was sourced to a person named Ali Sajjad, a village accountant from Mirzapur, and collected by Pandit Ram Gharib Chaube, and also noted to be an "imperfect version" of Princess Aubergine. [13]

Author M. N. Venkataswami collected an Indian tale titled The Fakeer's Daughter and the Wicked Queen. In this tale, a poor fakeer is visited by an even poorer fakeer in search of alms. The first fakeer's daughter becomes irritated with the second fakeer's insistence and drops a ladle of hot keer on the second fakeer's head, creating a blister on his hand. The second fakeer is instructed by the "angels from heaven" to let the blister be and, nine months later, a baby girl sprouts from the blister and asks for nourishing. The girl grows up and becomes a beautiful maiden. The rani of the place learns of the maiden's beauty, far surpassing her own, and decides to get rid of her, so she sends some servants to meet the maiden. The servants notice the "carcanet" (a collar) of jewels around her neck and, after a denied polite request, they take the jewels by force and bring them to the Rani. After the carcanet is hung up in the queen's room, the maiden dies. Her father, the second fakeer, is warned in a dream to place the body out in the open, under a sandalwood tree. Next to the body, flowers sprout and their fragrance draws the Raja to the maiden's resting place. He goes to pluck a beeda and eat, but four invisible paris ask him to bring back the jewels from the queen's room. The Raja takes the carcanet and places it on the sleeping maiden, who comes back to life, gives the beeda to the Raja and marries him, while the Rani is executed. [14]

Author Mary Frere collected a Southern India tale titled Sodewa Bai. In this tale, a Ranee and a Rajah have a beautiful daughter named Sodewa Bai ('Lady Good Fortune'), and they summon the wise men to divine her future. The wise men interpret she will be very rich - since flowers and pearls fall from her lips whenever she speaks -, but caution the royal couple that they protect the necklace on the girl's neck, since she was born with it and removing it would mean her death. Years later, when the girl is fourteen years old, she has not found any suitor. Her parents also give her a pair of tiny slippers of gold and jewels. One day, she goes with some haidmaidens to fetch wildflowers in the slopes surrounding her palace, and lets one of her slippers slip away down the mountain. After learning of the loss, her parents announce a great reward for anyone that can return the missing pair. Meanwhile, the slipper in found in a jungle by the son of another Rajah, and the prince and his father marvel at the slipper, and decide the boy shall look for its owner to marry her. News of the proclamation of Sodewa Bai's parents reach his kingdom (since the prince lives in the Kingdom of the Plains) and he goes to the Mountain Kingdom of Sodewa Bai to deliver the missing slipper, and ask her to marry him. Sodewa Bai's parents tell the prince they will allow their marriage only if their daughter agrees, which she does, and they marry in a grand ceremony. After a while, the prince wants to take Sodewa Bai to his home kingdom, and his parents-in-law warn him to never let his wife take off her necklace. The prince agrees and goes back home, and the tale explains he was already married to a previous co-wife, who begins to dislike the presence of Sodewa Bai, whom she considers a rival. Sometime later, the prince, named Rowjee Rajah, has to leave to some distant part of his kingdom, and leaves Sodewa Bai under the care of his previous co-wife. After he leaves, the first wife notices the golden necklace on Sodewa Bai's neck, and inquires about it. The girl naïvely reveals the secret of the necklace, and the first co-wife orders a "negress" to steal the object at night. The servant does and places it on her own neck; Sodewa Bai does not wake up the next day and her parents-in-law believe her to be dead, so they move their body to an open tomb near a water tank. After Rowjee Rajah returns, he learns of his second wife's apparent death and mourns for her. Meanwhile, at her tomb, Sodewa Bai awakes everytime the servant removes the necklace at night, and falls into her death-like sleep in the morning. As time passes, she gives birth to a son, and she leaves pearls to float in the water tank. Rowjee Rajah notices the pearls in the water and decides to investigate on the first days, but returns after the baby is born, and hears someone inside the tomb. The prince realizes Sodewa Bai is alive and is told about the necklace, which is not around her neck. The prince returns to the palace, retrieves his wife's necklace and restores her life. Sodewa Bai returns to the palace with her son, and the first co-wife and her servant are punished. [15]

In an Orissan tale collected from a Bhatra source in Nabarangpur district with the title Tale of Florist's Daughter and Serpent, a serpent opens its crest near a baby girl, which the girl's paternal aunt witnesses. Thinking the girl must be of the snake species, the baby's father abandons the baby in the forest under a tree. An old florist finds the baby crying and brings her home, keeping her hidden from his neighbours. The florist's wife contributes with the deception by pretending to be pregnant, then feigns labour pains and presents the baby girl as her own child. An astrologer then comes to name the girl and suggests the name Tulasa. When the girl grows a bit older, she goes to play with the princess by the king's fence, and the king's co-wives, afraid the girl might draw the king's attention away from her, expel her from approaching the palace. Later, when Tulasa becomes a beautiful young lady, she goes to the palace to sell some flowers. The co-queens notice their rival is there again, and decide to kill the girl and burn the body. They send some messengers to kill Tulasa in the jungle, but she tricks her would-be executors by saying her lifeforce is in the trunk of the king's prized elephant, which they should kill first. Tulasa escapes from the messengers, and her friend, the princess, learns of the co-queens' plot to kill the florist girl. The co-queens move to a second attempt; they order the messengers to kill her, and Tulasa, now, reveals the secret: somewhere in the seven seas, there are seven rooms, one with an idol inside; on the idol there are seven golden chains of seven tolas, wherein lies her death; the soldiers must behead the idol's head and the seven necklaces will be detached from its neck, killing her. The messengers follow Tulasa's instructions and destroy the idol and the necklaces, ending the girl's life. Thus, in order to cover up their crime, the messengers cover the girl's body and take her to be cremated, when the king arrives and asks them the meaning of their action. The messengers say they are taking a dead girl's body with no kith nor kin to be cremated, but the shroud falls from the body and reveals Tulasa's beauty to the king. Stunned at her beauty, the monarch orders them to explain themselves, when a monkey climbs down a tree and revives Tulasa with a herb. The little animal then explains everything to the king and says the girl is meant for him. At the end of the tale, the king executes his co-wives and takes Tulasa as his queen. [16]

Pakistan

In a Sindhi tale published by Sindhologist Nabi Bakhsh Baloch with the title The Ghaibi (Unseen) Queen (Sindhi: "غيبي راڻي"), a farmer grows watermelons in his orchard. One day, his wife goes to the orchard and hears a voice, then rushes to tell her husband about it. The couple return to the orchard and find a watermelon which they bring home. From the watermelon a baby girl appears, whom they raise as their daughter. When she grows up, news of her beauty draws many suitors, who are rejected. A king learns of her beauty and goes to the farmer's house to ask for her hand. Their marriage is arranged, and the king brings the watermelon girl to his palace. The king is previously married to two co-queens, who become increasingly jealous of the way the king dotes on the new girl, so they hire a dhooti (evil woman) to discover something about the new queen that the duo can use against her. The dhooti pays a visit to the third queen and they talk: unknowingly, the watermelon girl reveals her life (soul) is located inside a pearl in her necklace, which, if one is to remove from her, she would lose her life. Armed with this information, the dhooti steals the necklace and brings it to the other queens. The watermelon girl, who is pregnant, begins to feel dizzy and suffocated, and, sensing the upcoming danger, she tells the king to have her body safely installed in a room, instead of being buried, in case she dies. The jealous queens celebrate the "death" of their rival, and keep the necklace in a safe place. The watermelon girl eventually dies and, just as she requested, her body is placed in a room. Back to the queens, they alternate using the necklace by morning and hiding it at night, which causes the watermelon girl to revive at night and die by day. A baby son is born to the girl, who tells her child to explain the situation to his father, the king. Time passes, and the king decides to pass by the room where his third queen's body is kept, and finds a child playing by his wife's body. He decides to wait for the evening, and discovers the girl comes back to life to play with the baby. The king reunites with his wife and is told of the co-queens' plot, then they trace a course of action: he will steal back the necklace. The next day, the king sends a poor man near the palace to beg for alms, and asks for the necklace. The queens give the necklace to the beggar, who returns it to the king, who places it around the watermelon girl's neck. The king brings his wife and son back to the palace and expels the two queens. [17]

Egypt

Folklore scholar Hasan M. El-Shamy registers a single variant of type ATU 412 in the Middle East and Northern Africa, which he located in Egypt. [18]

Folklorist Howard Schwartz published a Jewish-Egyptian tale titled The Wonder Child: a rabbi and his wife pray to God to have a child. One night, at midnight, during Shevuoth, they pray to God. The rabbi's wife has a dream about a girl clutching a jewel in her hand, and a voice tells her that the child and the jewel can never be parted. Nine months later, she gives birth to a girl with a jewel, and names her Kohava ("star"). The rabbi also places the jewel inside a necklace. Kohava grows up to be a lovely and talented maiden. One day, the queen announces she will go to the bath house, and invites every woman. Kohava insists she wants to visit the bath house. Kohava goes to the bath house and draws everyone's attention due to her beauty. Even the queen notices she is more beautiful then herself, and fear her son, the prince, will wish to marry her. So the queen orders her servants to bring instruments for the girl to play, which she does with ease. Astonished by her talents, the queen convinces the girl's parents to take her to the palace as one of her musicians. Kohava's mother advises her daughter never to take the necklace off her. After they reach the palace, the queen orders Kohava to be sent to prison, so she can perish there, but a guard gives her food. A while later, the queen goes to check on Kohava, and sees she is still alive, but notices the glowing necklace. The queen takes the necklace by force and the girl falls asleep. The queen orders the guard to dispose of the body, but he simply places her inside a hut. Then, the queen's son, the prince, goes on a hunt and finds Kohava, lying asleep in the hut. He falls in love with her, but she cannot awake. At any rate, the prince goes back home and tells his mother he is in love with a princess, and the queen gives him Kohava's necklace as a betrothal gift for his bride. The prince goes back to the hut and places the necklace around Kohava's neck. She wakes up sees the prince; they each relate the story, and the prince learns of his mother's cruelty. The prince announces he will marry, and asks his mother to prepare a grand celebration. The bride is walked in wearing seven veils, and, when she lifts them, the queen sees Kohava is alive and flees. Kohava and the prince live happily ever after. [19] [20] In his notes, Schwartz noted it to be a cross between European tales Snow White and Sleeping Beauty. [21]

Caucasus Region

Georgia

The Georgian Folktale Index registers a similar narrative of a heroine's magical necklace, indexed as type 412, "The Marble Tears and Necklace". In the Georgian tale type, the heroine is capable of producing flower petals with her laughter and tears of pearls when she cries, and also possesses a magical necklace she can never part with. During the tale, the heroine falls into a death-like sleep when her rival steals the necklace. The prince, the heroine's husband, discovers the necklace, but it is their son that brings it back to the heroine. [22]

Armenia

In a tale collected by Susan Hoogasian-Villa from an Armenian-American source, The Fairy Child, a king overhears his youngest daughter talking that woman is more important that man. Angered at her commentary, he marries his two elder daughters to rich princes and the youngest to a poor man. Regardless of her poor situation, the third princess gives birth to a girl. One night, the baby girl is visited by four angels, who give her blessings. The first gives her a necklace she is to never part with, otherwise she will die; the other angels bestow marvellous gifts upon her: when she bathes, her bathwater turns to gold; when she cries, pearls fall from her eyes, and when she laughs, red roses will bloom on her cheeks. Later, when she grows up, the heroine, now a woman, alerts her helper, an old man, that her rival will steal her necklace, and the heroine will appear to be dead, but she is not to be buried. [23]

Karachay-Balkar people

In a tale from the Karachay-Balkars with the title "Алакез" ("Alakez"), an old couple suffer for not having children, until one day a girl is born to them, one cheek shining like the moon and the other like the sun. One night, as they place the girl in the cradle and occupy themselves with other chores, white genies come to the baby to bestow upon her gifts: the first ties a magical talisman (хамайылчи́к, 'hamayylchik') to her right hand, which will protect her at all times, and blesses her with the ability to cry diamond tears; the second blesses her with the ability to have gold appear whenever she bathes, and the third that wherever she steps flowers will appear. The girl grows up in beauty and charm, and, when she is of marriageable age, a young khan from a nearby khanate learns of her beauty and wishes to marry her. Thus, her parents prepare to send their daughter Alakez to the khan, escorted by an old woman neighbour and her own daughter. As they travel through a forest, the neighbour blinds Alakez and takes out her eyes, then dresses her own daughter as Alakez to trick the khan, and abandon the other girl in the woods. As the tale continues, a kind old man named Ivan takes Alakez in and she buys her eyes back. She also asks her friend Ivan to build a giant tower as her tomb, in case she dies, and the doors must open every day by themselves and mourn for her. Ivan fulfills her request. As for the neighbour woman, she learns of Alakez's magical talisman and orders a spy to steal it. He does and Alakez falls to the ground as if dead. Ivan then places her inert body in the tower. One night, the khan is riding next to the tower accompanied by a servant, and both hear the tower windows mourning for a girl. They enter the tower and see Alakez's dead body, the mark of a talisman on the right side of her body. The khan notices the servant has with him something that might be the perfect match, and bids him place it on the body. Alakez wakes up and asks to be taken to her friend Ivan and his wife, where the whole truth is told to the khan. [24] [25]

Turkey

Scholars Wolfram Eberhard and Pertev Naili Boratav devised a classification system for Turkish folktales and narratives, called Typen türkischer Volksmärchen ("Turkish Folktale Catalogue"). In their joint work, they registered a Turkish tale type indexed as TTV 240, "Rosenlachen und Perlenweinen" ("Rose-Laughter and Pearl-Tears"), with 29 variants listed. In the tale type, the heroine is born to a poor couple, and dervishes, fairies or peris come to bless the child with the ability to produce rose petals with her laughter and pearls with her tears, and also give her an amulet. Later in the tale, the heroine's rival steals the heroine's amulet; the heroine falls into a death-like sleep, and her body is placed in a mausoleum. [26]

Uzbekistan

In an Uzbek tale titled "Дочь дровосека" ("The Woodcutter's Daughter"), a poor and childless woodcutter earns his living by chopping firewood in the mountains and selling it. One day, he chops down a very old tree and releases a good djinn, who, in gratitude, explains an evil djinn imprisoned him there, and gives the man a magical apple for the man and his wife to eat. The good djinn explains a girl will be born to them, but one that produces pearls with her tears, flowers with her words, and golden sand wherever she steps on. It happens thus, and a girl is indeed born to them. As she grows up, her father demands a particularly steep dowry for her, which shuns many suitors. One day, however, the evil djinn appears and demands the man delivers him his daughter as wife, which he refuses to do. A young batyr comes and drives away the djinn, and the woodcutter, in return, agrees to marry his daughter to the batyr. Some time later, as the journey is long for them, and they are old, the woodcutter and his wife cannot make the journey, when suddenly a rich old woman comes with her daughter and offers to take the girl to her bridegroom, since the old woman is his aunt. The woodcutter agrees, but, during the journey, the old woman demands the girl's pearl-producing eyes and makes her blind. Later, the girl buys her eyes back. The old woman joins forces with the evil djinn, who tells her to fetch a certain golden fish in the river which contains a special earring that holds the girl's lifeforce within. The old woman does as instructed, takes the earring and wears it; the girl enters a death-like state and her body is placed on a tomb. However, the girl wakes up whenever the old woman removes the earring, and falls dead when the earring is worn. One day, the batyr, who is the girl's bridegroom, hunts a white dove and follows it to the tomb, where he finds his true bride. The girl wakes up and explains his aunt has the earring with her lifeforce inside. [27]

Male heroes

Lal Behari Dey collected a similar tale from Bengal in his work Folk-Tales of Bengal , albeit with a male hero. In this tale, Life's Secret, a king has two wives, Suo and Duo, both childless. One day, a fakeer goes to the palace to beg for alms, and is greeted by queen Suo, who gives him a handful of rice. In return, the fakeer gives her a nostrum, to be swallowed with the juice of a pomegranate flower; the queen will give birth to a son she will name Dalim Kumar ("Dalim" - pomegranate; "Kumar" - son). The fakeer also warns her that her son's life will be bound to a necklace of gold, inside a wooden box, inside a boal fish's heart that lives in a pool in the palace. In time, Suo gives birth to Dalim Kumar. The boy grows up and likes to play with pigeons. One day, a pigeon flies in Duo queen's quarters. Duo promises to return the pigeon if Dalim asks his mother the secret of this life. Dalim Kumar talks to his mother about it; at first, Suo relates in telling her son about it, but eventually concedes and tells him about the necklace. Dalim Kumar tells his step-mother about it. Duo begins a plan: with some herbs, she feigns that her bones are so frail that they crackle and pop, and her only cure is the boal fish. After the fish is caught, at the same time Dalim begins to feel unwell and, as the wooden box is open and Duo places Dalim's necklace around her neck, Dalim falls dead. The king's grief is so deep, and he orders his son's body to be placed in one of his garden-houses, with provisions, and trusts the son of his prime minister, Dalim Kumar's friend, with the keys to his tomb. Dalim Kumar wakes up at night while his step-mother does not wear the necklace, and dies in the daytime so long as Duo wears the necklace. After some time, the prime minister's son notices that, despite being dead, Dalim Kumar's body does not decay, and decides to investigate further. Dalim Kumar's friends discovers he is alive, and both plot to retrieve the necklace. Meanwhile, BIdhata-Purusha's sister gives birth to a daughter, and Bidhata-Purusha prophesises his niece shall marry a dead bridegroom. After she comes of age, her mother takes the girl with her to avoid her fate, and they reach Dalim Kumar's garden-palace. The girl enters the palace and meets Dalim Kumar, who claims to be her future dead bridegroom. Dalim Kumar's friend marries them and leaves them be. The next day, Dalim Kumar "dies" again, to his wife's consternation, but revives at night. The girl learns of his condition and, after some years, and the birth of their two children, decides to meet her step-mother-in-law and retrieve her husband's necklace. The girl disguises herself as a poor female barber and goes to Queen Duo's palace to hire herself. Unaware of the girl's identity, she takes her in as her servant. The girl instructs her elder son to play with the necklace around Duo's neck, and to cry if the boy parts with it. Duo lets the child play with the necklace, certain of her triumph. Dalim Kumar's wife steals the necklace and brings it back to her husband. Dalim Kumar, his friend and his family enter the king's palace with grandeur; the prince meets his parents and tells the whole truth. The king then sentences his queen Duo to be buried alive. [28]

In a tale collected by Tapanmohan Chatterji with the title Dalim-Koumar ou Le Prince Grenade, a king has two queens, Suo and Duo. Suo has a child, while Duo is childless, and envies the other. Suo's son is named Dalim-Koumar, since his life is tied to a pomegranate. One day, one of Dalim's doves flies to Duo's room and she catches it. Duo promises to return it, if the boy reveals where his "life" is. The boy retorts that his life is inside him, but the queen explains that an astrologer told the boy's mother the boy's life is inside the pomegranate, and Duo wants to know where it is. Dalim runs to his mother to ask her about it and, despite some avoidance, Suo tells him the secret. Dalim goes to tell Duo the information. Some time later, queen Duo feigns illness, and she tells the king her only cure is a certain pomegranate on a certain tree that lies away from the village. The king's servant takes the pomegranate from the tree, which instantly causes the boy to fall ill. Duo cracks open the fruit and finds a little box with a golden necklace inside. She wears it on her neck and Dalim falls dead immediately. The king and Suo cry for their lost son, and order his body to be placed inside a white marbled pavilion. Meanwhile, Dalim Kumar's fiancée, a princess, prepares herself for the sati, but promises to defeat death by the strength of her love and by giving offerings to the gods. The princess decides to vigil his body alone, in the pavilion. All the while, queen Suo retires to her chambers out of grief, and Duo becomes the king's favourite, being showered with affection and jewels, but, in order to avoid suspicions, takes off the necklace at night - which revives Dalim in his tomb. Thus, Dalim revives at night and dies in the morning. One day, Dalim Kumar awakes and sees the princess, his fiancée, in the pavilion, and they embrace. The prince tells the princess about the necklace, and she promises to fetch it and give it to him. After Dalim falls into a sleep again, the princess disguise herself as a barber woman and goes to queen Duo's palace. With a child in tandem, the princess convinces Duo to let the child play with the necklace. After fulfilling her task, the princess takes the necklace back to Dalim Kumar. He awakes and embraces his fiancée, thanking her for her help. The next day, Dalim Kumar and the princess enter his father's city to let him know his son is alive, and to punish the perfidious queen. [29]

In a tale collected by author Mary Frere with the title Chundun Rajah, seven princes marry seven wives, who mistreat their sister-in-law, the princes' sister, except the seventh prince's wife. The women spread rumours about the princess until her brothers expel her from home. As a last humiliation, they shout at the princess to not return home until she marries Chundun Rajah ("King Sandlewood"), and when she does, to set wooden stools for them. The princess is given some food for the road, and finds a Rakshas's house. The Rakshas's pets, a little cat and a little dog, ask for some food and in returns let the princess take some of the Rakshas's antimony and saffron. Later, the princes finds a large tomb in the middle of the jungle, and enters it. The story then explains that the tomb belongs to Chundun Rajah: his family laid his body in the tomb, and, though many months have passed, his body has not decayed, because he comes alive at night and dies in the morning, and this only a Brahmin know. One night, Chundun Rajah wakes up and sees the princess. They tell each other their stories. Chundun Rajah marries the princess with the blessing of his Brahmin friend, and, one day, explains the origin of his malaise to the princess: a flying peri fell in love with Chundun Rajah, but he refused her advances, and, in vengeance, the peri stole the Chundun Har ("sandlewood necklace") that stored the youth's life within. In time, the princess gives birth to a boy, but, due to worry for her husband's state, she begins to fall ill. Their Brahmin friends suggests she seeks shelter with her relatives-in-law (Chundun Rajah's mother and sister), and to sit on a marble slab in their garden, which was Chundun's favourite. The princess takes her son and goes to her mother-in-law's palace to sit on the marble slab. Chundun Rajah's sisters notice her presence and go to talk to her, and notice that the little boy was very reminiscent of their dead brother. They take the princess and her son and give her a house to live in. Days pass, and Chundun Rajah's sisters hear some voices coming from the princess's house, and pay her a visit: they see their brother, Chundun Rajah, alive and well, and playing with his son. After a joyous reunion, Chundun Rajah tells them of the peri and the necklace. Some time later, Chundun Kumar is playing with his son in his wife's house, and the flying peris come in unseen, even the one wearing his necklace. Chundun's son sees that specific peri and tears off the necklace from her neck, making its beads fall to the ground. The peris fly out of the house, while the princess gathers the beads, rebuild the necklace and puts it on her husband's neck, ending his curse once and for all. Later, the princess invite her own brothers and their wives to her wedding to Chundun Rajah. Remembering her sisters-in-law's mocking remark, the princess has six of them sat on wooden stools, while the only one that was kind to her is given a better stool. [30]

In a tale collected by Sunity Devi, Maharani of Coochbehar, with the title The Dead Prince, an astrologer has a sister. His sister gives birth to a girl and, after six days, asks her brother to predict her daughter's future - since, on the sixth day after birth, one's own future is written on their forehead by the Creator. The astrologer prophecizes that she will marry a dead man. Trying to avoid this fate, the girl's mother takes her daughter after she is 12 or 13 years old and wanders through a forest. Meanwhile, a Maharajah has two wives, a first Maharani with a son named Dalim Kumar, and a second Maharani, with no son. The second Maharani hates her step-son. One day, the prince is found dead, apparently he drowned while in the castle's grounds. The second Maharani suggests her husband burn the prince's body, but the boy's grieving mother asks her husband to build a palace to house the prince's body, with his instruments and provisions for 10 years. The Maharajah fulfills her request. Back to the girl and her mother, they are still wandering through forests and jungles, and the girl says she is thirsty. The girl stops to rest by a tree, while her mother goes in front of her to find any water source. They get separated: the mother thinks she lost her daughter and returns home, while the girl reaches the palace in the jungle. While she is there, one evening, the prince awakes and sees her. Days, months pass, and the girl and prince begin to like each other and marry. One day, the girl, now a woman, asks the prince his story. He tells that an astrologer predicted at the time of his birth his destiny as a great ruler, if he lived, and gave his father a necklace (which was "his life"), with a warning to not allow anyone wear it around their neck. So, to protect his son, the Maharajah places the necklace in a golden box and hid in the depths of a pool in the palace. However, the Maharajah's second wife, who also knew of the necklace, and ordered the fisherman to catch the fish that swallowed the golden box. The second Maharani stole the necklace and wore it around her neck - and it has been like this since then: whenever she wears the necklace in the morning, the prince dies, but come night, she takes off the necklace and the prince is alive. After hearing the story, the prince's wife, then, promises to get back the necklace. Some time later, some of the Maharajah's huntsmen and sportsmen report back to him that the prince's palace is haunted, since they hear a woman's voice and a baby's cry. The Maharajah ponders that, if his son was alive, he would have married and fathered a child at that time, but dismisses the huntsmen's concerns. Back to the prince's wife, she takes her child, disguises herself as a poor woman ("naptini") and goes to her father-in-law's palace to hire herself as a servant to the second Maharani. She has the Maharani play with her child, while she paints her feet, and the baby plays with the necklace. The prince's wife steals the necklace and rushes back to Dalim Kumar's palace to give him. Later, Dalim Kumar is visited by his father and mother, who rejoice that their son is alive. The prince suggests they throw the necklace to the depths of the ocean. Finally, the girl's mother learns of her daughter's survival and her story, and thanks her brother for his prediction. [31]

In a tale from Assam, titled A Dead Husband, a man named Bidhata ("destiny") rules over fate. After his sister gives birth to a girl, Bidhata predicts that the girl shall have no want of food and drink, but she shall marry a dead husband. Trying to avoid this fate, Bidhata's sisters take her daughter and wander off. They reach a large, uninhabited palace on the way, and the girl is impelled inside it, leaving her mother outside the palace door. Inside, the girl cries due to being separated from her mother, but, at night, a handsome youth appears to her. The youth assuages her fears, and tells her he will die in the morning. The girl becomes a woman, and lives with the youth. One day, the youth explains he is a prince; his mother placed a necklace on his neck; after his mother died, his father remarried, and his new step-mother hated the prince and stole his necklace, causing him to fall into a death-like sleep immediately. The prince's step-mother placed the necklace in a water jug, and he wishes someone can retrieve the necklace. The prince's wife takes their child and goes to her father-in-law's palace to steal the necklace. She enters service as a maid, and wins the queen's trust. After some time, she takes back the necklace and rushes back to her husband. He is given the necklace and comes alive again. The prince goes back to his father and tells him the whole story. The king executes his wife, and welcomes his son and daughter-in-law. [32] [33]