The gambler's fallacy, also known as the Monte Carlo fallacy or the fallacy of the maturity of chances, is the incorrect belief that, if an event has occurred more frequently than expected, it is less likely to happen again in the future. The fallacy is commonly associated with gambling, where it may be believed, for example, that the next dice roll is more than usually likely to be six because there have recently been fewer than the expected number of sixes.

Minmax is a decision rule used in artificial intelligence, decision theory, game theory, statistics, and philosophy for minimizing the possible loss for a worst case scenario. When dealing with gains, it is referred to as "maximin" – to maximize the minimum gain. Originally formulated for several-player zero-sum game theory, covering both the cases where players take alternate moves and those where they make simultaneous moves, it has also been extended to more complex games and to general decision-making in the presence of uncertainty.

A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. Individuals create their own "subjective reality" from their perception of the input. An individual's construction of reality, not the objective input, may dictate their behavior in the world. Thus, cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, and irrationality.

A heuristic, or heuristic technique, is any approach to problem solving or self-discovery that employs a practical method that is not guaranteed to be optimal, perfect, or rational, but is nevertheless sufficient for reaching an immediate, short-term goal or approximation. Where finding an optimal solution is impossible or impractical, heuristic methods can be used to speed up the process of finding a satisfactory solution. Heuristics can be mental shortcuts that ease the cognitive load of making a decision.

Bounded rationality is the idea that rationality is limited when individuals make decisions, and under these limitations, rational individuals will select a decision that is satisfactory rather than optimal.

In economics and finance, risk aversion is the tendency of people to prefer outcomes with low uncertainty to those outcomes with high uncertainty, even if the average outcome of the latter is equal to or higher in monetary value than the more certain outcome.

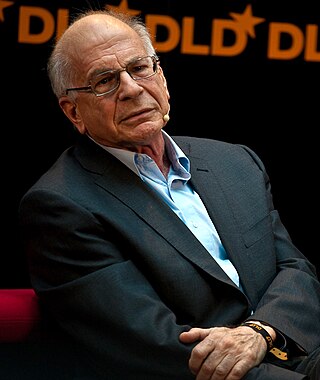

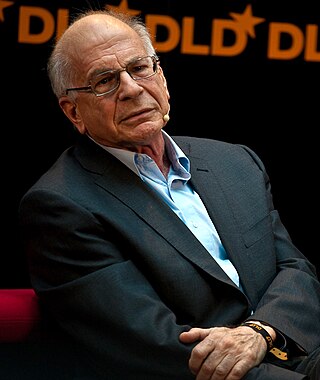

Prospect theory is a theory of behavioral economics, judgment and decision making that was developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979. The theory was cited in the decision to award Kahneman the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics.

The representativeness heuristic is used when making judgments about the probability of an event being representional in character and essence of known prototypical event. It is one of a group of heuristics proposed by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the early 1970s as "the degree to which [an event] (i) is similar in essential characteristics to its parent population, and (ii) reflects the salient features of the process by which it is generated". The representativeness heuristic works by comparing an event to a prototype or stereotype that we already have in mind. For example, if we see a person who is dressed in eccentric clothes and reading a poetry book, we might be more likely to think that they are a poet than an accountant. This is because the person's appearance and behavior are more representative of the stereotype of a poet than an accountant.

Loss aversion is a psychological and economic concept which refers to how outcomes are interpreted as gains and losses where losses are subject to more sensitivity in people's responses compared to equivalent gains acquired. Kahneman and Tversky (1992) have suggested that losses can be twice as powerful, psychologically, as gains. When defined in terms of the utility function shape as in the cumulative prospect theory (CPT), losses have a steeper utility than gains, thus being more "painful" than the satisfaction from a comparable gain as shown in Figure 1. Loss aversion was first proposed by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman as an important framework for prospect theory – an analysis of decision under risk.

The conjunction fallacy is an inference that a conjoint set of two or more specific conclusions is likelier than any single member of that same set, in violation of the laws of probability. It is a type of formal fallacy.

The recognition heuristic, originally termed the recognition principle, has been used as a model in the psychology of judgment and decision making and as a heuristic in artificial intelligence. The goal is to make inferences about a criterion that is not directly accessible to the decision maker, based on recognition retrieved from memory. This is possible if recognition of alternatives has relevance to the criterion. For two alternatives, the heuristic is defined as:

If one of two objects is recognized and the other is not, then infer that the recognized object has the higher value with respect to the criterion.

Gerd Gigerenzer is a German psychologist who has studied the use of bounded rationality and heuristics in decision making. Gigerenzer is director emeritus of the Center for Adaptive Behavior and Cognition (ABC) at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and director of the Harding Center for Risk Literacy, both in Berlin.

The Allais paradox is a choice problem designed by Maurice Allais (1953) to show an inconsistency of actual observed choices with the predictions of expected utility theory. Rather than adhering to rationality, the Allais paradox proves that individuals rarely make rational decisions consistently when required to do so immediately. The independence axiom of expected utility theory, which requires that the preferences of an individual should not change when altering two lotteries by equal proportions, was proven to be violated by the paradox.

The "hot hand" is a phenomenon, previously considered a cognitive social bias, that a person who experiences a successful outcome has a greater chance of success in further attempts. The concept is often applied to sports and skill-based tasks in general and originates from basketball, where a shooter is more likely to score if their previous attempts were successful; i.e., while having the "hot hand.” While previous success at a task can indeed change the psychological attitude and subsequent success rate of a player, researchers for many years did not find evidence for a "hot hand" in practice, dismissing it as fallacious. However, later research questioned whether the belief is indeed a fallacy. Some recent studies using modern statistical analysis have observed evidence for the "hot hand" in some sporting activities; however, other recent studies have not observed evidence of the "hot hand". Moreover, evidence suggests that only a small subset of players may show a "hot hand" and, among those who do, the magnitude of the "hot hand" tends to be small.

Heuristics is the process by which humans use mental shortcuts to arrive at decisions. Heuristics are simple strategies that humans, animals, organizations, and even machines use to quickly form judgments, make decisions, and find solutions to complex problems. Often this involves focusing on the most relevant aspects of a problem or situation to formulate a solution. While heuristic processes are used to find the answers and solutions that are most likely to work or be correct, they are not always right or the most accurate. Judgments and decisions based on heuristics are simply good enough to satisfy a pressing need in situations of uncertainty, where information is incomplete. In that sense they can differ from answers given by logic and probability.

The certainty effect is the psychological effect resulting from the reduction of probability from certain to probable. It is an idea introduced in prospect theory.

Social heuristics are simple decision making strategies that guide people's behavior and decisions in the social environment when time, information, or cognitive resources are scarce. Social environments tend to be characterised by complexity and uncertainty, and in order to simplify the decision-making process, people may use heuristics, which are decision making strategies that involve ignoring some information or relying on simple rules of thumb.

Ecological rationality is a particular account of practical rationality, which in turn specifies the norms of rational action – what one ought to do in order to act rationally. The presently dominant account of practical rationality in the social and behavioral sciences such as economics and psychology, rational choice theory, maintains that practical rationality consists in making decisions in accordance with some fixed rules, irrespective of context. Ecological rationality, in contrast, claims that the rationality of a decision depends on the circumstances in which it takes place, so as to achieve one's goals in this particular context. What is considered rational under the rational choice account thus might not always be considered rational under the ecological rationality account. Overall, rational choice theory puts a premium on internal logical consistency whereas ecological rationality targets external performance in the world. The term ecologically rational is only etymologically similar to the biological science of ecology.

In behavioural sciences, social rationality is a type of decision strategy used in social contexts, in which a set of simple rules is applied in complex and uncertain situations.

Ralph Hertwig is a German psychologist whose work focuses on the psychology of human judgment and decision making. Hertwig is Director of the Center for Adaptive Rationality at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, Germany. He grew up with his brothers Steffen Hertwig and Michael Hertwig in Talheim, Heilbronn.