Geology is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth sciences, including hydrology. It is integrated with Earth system science and planetary science.

Anatase is a metastable mineral form of titanium dioxide (TiO2) with a tetragonal crystal structure. Although colorless or white when pure, anatase in nature is usually a black solid due to impurities. Three other polymorphs (or mineral forms) of titanium dioxide are known to occur naturally: brookite, akaogiite, and rutile, with rutile being the most common and most stable of the bunch. Anatase is formed at relatively low temperatures and found in minor concentrations in igneous and metamorphic rocks. Glass coated with a thin film of TiO2 shows antifogging and self-cleaning properties under ultraviolet radiation.

In geology, rock is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks form the Earth's outer solid layer, the crust, and most of its interior, except for the liquid outer core and pockets of magma in the asthenosphere. The study of rocks involves multiple subdisciplines of geology, including petrology and mineralogy. It may be limited to rocks found on Earth, or it may include planetary geology that studies the rocks of other celestial objects.

In mineralogy, crystal habit is the characteristic external shape of an individual crystal or aggregate of crystals. The habit of a crystal is dependent on its crystallographic form and growth conditions, which generally creates irregularities due to limited space in the crystallizing medium.

A convergent boundary is an area on Earth where two or more lithospheric plates collide. One plate eventually slides beneath the other, a process known as subduction. The subduction zone can be defined by a plane where many earthquakes occur, called the Wadati–Benioff zone. These collisions happen on scales of millions to tens of millions of years and can lead to volcanism, earthquakes, orogenesis, destruction of lithosphere, and deformation. Convergent boundaries occur between oceanic-oceanic lithosphere, oceanic-continental lithosphere, and continental-continental lithosphere. The geologic features related to convergent boundaries vary depending on crust types.

Andesite is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predominantly of sodium-rich plagioclase plus pyroxene or hornblende.

Vivianite (Fe2+

3(PO

4)

2·8H

2O) is a hydrated iron phosphate mineral found in a number of geological environments. Small amounts of manganese Mn2+, magnesium Mg2+, and calcium Ca2+ may substitute for iron Fe2+ in the structure. Pure vivianite is colorless, but the mineral oxidizes very easily, changing the color, and it is usually found as deep blue to deep bluish green prismatic to flattened crystals.

Vivianite crystals are often found inside fossil shells, such as those of bivalves and gastropods, or attached to fossil bone.

Forearc is a plate tectonic term referring to a region in a subduction zone between an oceanic trench and the associated volcanic arc. Forearc regions are present along convergent margins and eponymously form 'in front of' the volcanic arcs that are characteristic of convergent plate margins. A back-arc region is the companion region behind the volcanic arc.

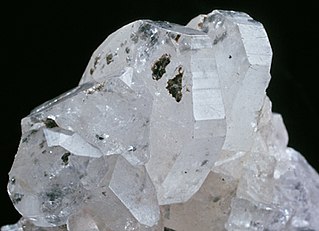

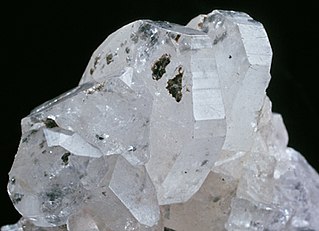

Phenakite or phenacite is a fairly rare nesosilicate mineral consisting of beryllium orthosilicate, Be2SiO4. Occasionally used as a gemstone, phenakite occurs as isolated crystals, which are rhombohedral with parallel-faced hemihedrism, and are either lenticular or prismatic in habit: the lenticular habit is determined by the development of faces of several obtuse rhombohedra and the absence of prism faces. There is no cleavage, and the fracture is conchoidal. The Mohs hardness is high, being 7.5–8; the specific gravity is 2.96. The crystals are sometimes perfectly colorless and transparent, but more often they are greyish or yellowish and only translucent; occasionally they are pale rose-red. In general appearance the mineral is not unlike quartz, for which indeed it has been mistaken. Its name comes from Ancient Greek: φέναξ, romanized: phénax, meaning "deceiver" due to its close visual similarity to quartz, named by Nils Gustaf Nordenskiöld in 1833.

Natrolite is a tectosilicate mineral species belonging to the zeolite group. It is a hydrated sodium and aluminium silicate with the formula Na2Al2Si3O10·2H2O. The type locality is Hohentwiel, Hegau, Germany.

Heulandite is the name of a series of tecto-silicate minerals of the zeolite group. Prior to 1997, heulandite was recognized as a mineral species, but a reclassification in 1997 by the International Mineralogical Association changed it to a series name, with the mineral species being named:

The rock cycle is a basic concept in geology that describes transitions through geologic time among the three main rock types: sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous. Each rock type is altered when it is forced out of its equilibrium conditions. For example, an igneous rock such as basalt may break down and dissolve when exposed to the atmosphere, or melt as it is subducted under a continent. Due to the driving forces of the rock cycle, plate tectonics and the water cycle, rocks do not remain in equilibrium and change as they encounter new environments. The rock cycle explains how the three rock types are related to each other, and how processes change from one type to another over time. This cyclical aspect makes rock change a geologic cycle and, on planets containing life, a biogeochemical cycle.

In geology, a clastic wedge is a thick accumulation of sediments or sedimentary rocks eroded and deposited landward of a mountain chain or geological boundary. They begin at the mountain front, thicken considerably landwards of it to a peak depth, and progressively thin with increasing distance inland. As they are often lens-shaped in profile, the process by which these sedimentary wedges are shaped is due to the regressive and transgressive movement from bodies of water. Some examples of clastic wedges in the United States are the Catskill Delta in Appalachia and the sequence of Jurassic and Cretaceous sediments deposited in the Cordilleran foreland basin in the Rocky Mountains.

In geology, texture or rock microstructure refers to the relationship between the materials of which a rock is composed. The broadest textural classes are crystalline, fragmental, aphanitic, and glassy. The geometric aspects and relations amongst the component particles or crystals are referred to as the crystallographic texture or preferred orientation. Textures can be quantified in many ways. The most common parameter is the crystal size distribution. This creates the physical appearance or character of a rock, such as grain size, shape, arrangement, and other properties, at both the visible and microscopic scale.

An accretionary wedge or accretionary prism forms from sediments accreted onto the non-subducting tectonic plate at a convergent plate boundary. Most of the material in the accretionary wedge consists of marine sediments scraped off from the downgoing slab of oceanic crust, but in some cases the wedge includes the erosional products of volcanic island arcs formed on the overriding plate.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to geology:

This glossary of geology is a list of definitions of terms and concepts relevant to geology, its sub-disciplines, and related fields. For other terms related to the Earth sciences, see Glossary of geography terms.

The Sumatra Trench is a part of the Sunda Trench or Java Trench. The Sunda subduction zone is located in the east part of Indian Ocean, and is about 300 km (190 mi) from the southwest coast of Sumatra and Java islands. It extends over 5,000 km (3,100 mi) long, starting from Myanmar in the northwest and ending at Sumba Island in the southeast.

Mottramite is an orthorhombic anhydrous vanadate hydroxide mineral, PbCu(VO4)(OH), at the copper end of the descloizite subgroup. It was formerly called cuprodescloizite or psittacinite (this mineral characterized in 1868 by Frederick Augustus Genth). Duhamelite is a calcium- and bismuth-bearing variety of mottramite, typically with acicular habit.

The geology of Myanmar is shaped by dramatic, ongoing tectonic processes controlled by shifting tectonic components as the Indian plate slides northwards and towards Southeast Asia. Myanmar spans across parts of three tectonic plates separated by north-trending faults. To the west, a highly oblique subduction zone separates the offshore Indian plate from the Burma microplate, which underlies most of the country. In the center-east of Myanmar, a right lateral strike slip fault extends from south to north across more than 1,000 km (620 mi). These tectonic zones are responsible for large earthquakes in the region. The India-Eurasia plate collision which initiated in the Eocene provides the last geological pieces of Myanmar, and thus Myanmar preserves a more extensive Cenozoic geological record as compared to records of the Mesozoic and Paleozoic eras. Myanmar is physiographically divided into three regions: the Indo-Burman Range, Myanmar Central Belt and the Shan Plateau; these all display an arcuate shape bulging westwards. The varying regional tectonic settings of Myanmar not only give rise to disparate regional features, but they also foster the formation of petroleum basins and a diverse mix of mineral resources.