Manorialism, also known as the manor system or manorial system, was the method of land ownership in parts of Europe, notably England, during the Middle Ages. Its defining features included a large, sometimes fortified manor house in which the lord of the manor and his dependents lived and administered a rural estate, and a population of labourers who worked the surrounding land to support themselves and the lord. These labourers fulfilled their obligations with labour time or in-kind produce at first, and later by cash payment as commercial activity increased. Manorialism is sometimes included in the definition of feudalism.

Copyhold tenure was a form of customary tenure of land common in England from the Middle Ages. The land was held according to the custom of the manor, and the mode of landholding took its name from the fact that the "title deed" received by the tenant was a copy of the relevant entry in the manorial court roll. A tenant – or mesne lord – who held land in this way was legally known as a copyholder.

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, a chief, or a ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are entitled to courtesy titles. The collective "Lords" can refer to a group or body of peers.

Enclosure or Inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or "common land" enclosing it and by doing so depriving commoners of their rights of access and privilege. Agreements to enclose land could be either through a "formal" or "informal" process. The process could normally be accomplished in three ways. First there was the creation of "closes", taken out of larger common fields by their owners. Secondly, there was enclosure by proprietors, owners who acted together, usually small farmers or squires, leading to the enclosure of whole parishes. Finally there were enclosures by Acts of Parliament.

Robert Livingston the Elder was a merchant, fur trader and government official in colonial New York. He was granted a patent to 160,000 acres of land along the Hudson River, becoming the first lord of Livingston Manor.

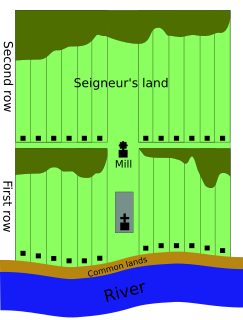

The manorial system of New France, known as the seigneurial system, was the semi-feudal system of land tenure used in the North American French colonial empire.

The Middle Colonies were a subset of the Thirteen Colonies in British America, located between the New England Colonies and the Southern Colonies. Along with the Chesapeake Colonies, this area now roughly makes up the Mid-Atlantic states.

The Province of New York (1664–1776) was a British proprietary colony and later royal colony on the northeast coast of North America. As one of the Middle Colonies, New York achieved independence and worked with the others to found the United States.

The Province of New Jersey was one of the Middle Colonies of Colonial America and became the U.S. state of New Jersey in 1783. The province had originally been settled by Europeans as part of New Netherland but came under English rule after the surrender of Fort Amsterdam in 1664, becoming a proprietary colony. The English renamed the province after the Bailiwick of Jersey in the English Channel. The Dutch Republic reasserted control for a brief period in 1673–1674. After that it consisted of two political divisions, East Jersey and West Jersey, until they were united as a royal colony in 1702. The original boundaries of the province were slightly larger than the current state, extending into a part of the present state of New York, until the border was finalized in 1773.

Lord of the manor is a title that, in Anglo-Saxon England, referred to the landholder of a rural estate. The lord enjoyed manorial rights as well as seignory, the right to grant or draw benefit from the estate. The title continues in modern England and Wales as a legally recognised form of property that can be held independently of its historical rights. It may belong entirely to one person or be a moiety shared with other people.

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were held the lord's manorial courts, communal meals with manorial tenants and great banquets. The term is today loosely applied to various country houses, frequently dating from the late medieval era, which formerly housed the landed gentry.

The Inclosure Acts, which use an archaic spelling of the word now usually spelt "enclosure", cover enclosure of open fields and common land in England and Wales, creating legal property rights to land previously held in common. Between 1604 and 1914, over 5,200 individual enclosure acts were passed, affecting 28,000 km2.

A leasehold estate is an ownership of a temporary right to hold land or property in which a lessee or a tenant holds rights of real property by some form of title from a lessor or landlord. Although a tenant does hold rights to real property, a leasehold estate is typically considered personal property.

In common law systems, land tenure is the legal regime in which land is owned by an individual, who is said to "hold" the land. It determines who can use land, for how long and under what conditions. Tenure may be based both on official laws and policies, and on informal customs. In other words, land tenure system implies a system according to which land is held by an individual or the actual tiller of the land. It determines the owner's rights and responsibilities in connection with their holding. The French verb "tenir" means "to hold" and "tenant" is the present participle of "tenir". The sovereign monarch, known as The Crown, held land in its own right. All private owners are either its tenants or sub-tenants. Tenure signifies the relationship between tenant and lord, not the relationship between tenant and land. Over history, many different forms of land ownership, i.e., ways of owning land, have been established.

Quia Emptores is a statute passed by the Parliament of England in 1290 during the reign of Edward I that prevented tenants from alienating their lands to others by subinfeudation, instead requiring all tenants who wished to alienate their land to do so by substitution. The statute, along with its companion statute Quo Warranto also passed in 1290, was intended to remedy land ownership disputes and consequent financial difficulties that had resulted from the decline of the traditional feudal system in England during the High Middle Ages. The name Quia Emptores derives from the first two words of the statute in its original mediaeval Latin, which can be translated as "because the buyers". Its long title is A Statute of our Lord The King, concerning the Selling and Buying of Land. It is also cited as the Statute of Westminster III, one of many English and British statutes with that title.

In the United States, a patroon was a landholder with manorial rights to large tracts of land in the 17th century Dutch colony of New Netherland on the east coast of North America. Through the Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions of 1629, the Dutch West India Company first started to grant this title and land to some of its invested members. These inducements to foster colonization and settlement are the basis for the patroon system. By the end of the eighteenth century, virtually all of the American states had abolished primogeniture and entail; thus patroons and manors evolved into simply large estates subject to division and leases.

The Manor of Rensselaerswyck, Manor Rensselaerswyck, Van Rensselaer Manor, or just simply Rensselaerswyck, was the name of a colonial estate—specifically, a Dutch patroonship and later an English manor—owned by the van Rensselaer family that was located in the area that would later become the Capital District of New York in the United States.

A lordship is a territory held by a lord. It was a landed estate that served as the lowest administrative and judicial unit in rural areas. It originated as a unit under the feudal system during the Middle Ages. In a lordship, the functions of economic and legal management are assigned to a lord, who, at the same time, is not endowed with indispensable rights and duties of the sovereign. Lordship in its essence is clearly different from the fief and, along with the allod, is one of the ways to exercise the right.

A heerlijkheid was a landed estate that served as the lowest administrative and judicial unit in rural areas in the Dutch-speaking Low Countries before 1800. It originated as a unit of lordship under the feudal system during the Middle Ages. The English equivalents are manor, seigniory, and lordship. The German equivalent is Herrschaft. The heerlijkheid system was the Dutch version of manorialism that prevailed in the Low Countries and was the precursor to the modern municipality system in the Netherlands and Flemish Belgium.

Wilhelmus Hendricksen Beekman — also known as William Beekman and Willem Beekman — was a Dutch immigrant to America who came to New Amsterdam from the Netherlands in the same vessel with Director-General and later Governor Peter Stuyvesant.