In psychology, prospection is the generation and evaluation of mental representations of possible futures. The term therefore captures a wide array of future-oriented psychological phenomena, including the prediction of future emotion (affective forecasting), the imagination of future scenarios (episodic foresight), and planning. Prospection is central to various aspects of human cognition and motivation. Daniel Gilbert (psychologist) and Timothy Wilson coined the term in 2007. It has since become a central area of enquiry in the cognitive sciences. [1] [2] [3]

Even fundamental learning processes are, in some sense, forms of prospection. [4] [5] Associative learning enables individual animals to track local regularities in their environments and adapt their behaviour accordingly, in order to maximise their chances of positive outcomes and minimise risks. Animals that are capable of positive and negative states (for example pleasure and pain) can eventually learn about the consequences of their actions and thereby predict imminent rewards and punishments before they occur. This enables animals to change their current actions accordingly in line with prospective consequences.

Mental time travel refers to the ability to mentally reconstruct personal events from the past (known as episodic memory), as well as to imagine personal future events (known as episodic foresight). Mental time travel into the future (episodic foresight or episodic future thinking) is therefore one of several types of 'prospection' that refers to the capacity to simulate or imagine personal future events. [6] [7]

Episodic foresight is the capacity to imagine personal future scenarios and shape current action accordingly. [8]

The feelings evoked during episodic foresight enable people to infer how they would really feel if the event were to happen in reality. This thereby enables people to anticipate whether future events are desirable or undesirable, and ability called 'affective forecasting'. [9]

Simulating the future enables people to create intentions for future actions. Prospective memory is the form of memory that involves remembering to perform these planned intentions, or to recall them at some future point in time. [10] Prospective memory tasks are common in everyday life, ranging from remembering to post a letter to remembering to take one's medication.

People anticipate that it is possible to shape their future self. To acquire new knowledge or additional skills, people therefore engage in repeated actions driven by the goal to improve these future capacities. This deliberate practice is essential not only for elite performance but also in the acquirement of numerous everyday feats.

Intertemporal choices are choices with outcomes that play out over time. [11] Such decisions are ubiquitous in everyday life, ranging from routine decisions about what to eat for lunch (i.e. whether to adhere to a diet) to more profound decisions about climate change (i.e. whether to reduce current energy expenditure to avoid delayed costs). The ability to imagine future scenarios and adjust decisions accordingly may be important for making intertemporal choices in a flexible manner that accords with delayed consequences. Accumulating evidence suggests that cuing people to imagine the future in vivid detail can encourage preferences for delayed outcomes over immediate ones. [12] [13] This has been extended into real-world decisions such as in reducing the consumption of high-calorie food [14] and increasing pro-environmental behaviours. [15]

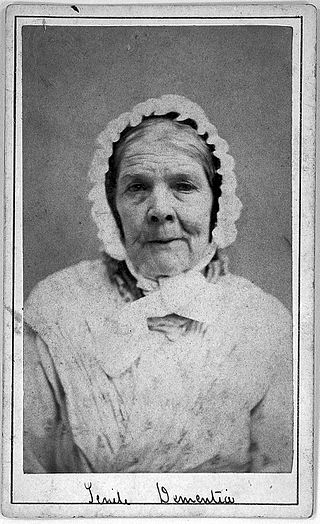

In recent years there have been a range of investigations into variation in prospection and its functions in clinical populations. Deficits to the mechanisms and functions of prospection have been observed in Alzheimer's disease and other age-related dementias, [16] Schizophrenia, and after brain damage (especially to the medial temporal lobes). [17]

Shifts in the content and modes of prospection have been observed in affective disorders. [18] [19] For example, in both clinical depression and anxiety there is an overrepresentation of possible negative future events. In depression, there is additionally a reduction in the generation of possible positive future events. There are also a range of changes to the representational format (i.e. whether people tend to represent the future in episodic or semantic detail) in affective disorders. [20] [21]

Cognitive psychology is the scientific study of human mental processes such as attention, language use, memory, perception, problem solving, creativity, and reasoning. Cognitive psychology originated in the 1960s in a break from behaviorism, which held from the 1920s to 1950s that unobservable mental processes were outside the realm of empirical science. This break came as researchers in linguistics and cybernetics, as well as applied psychology, used models of mental processing to explain human behavior. Work derived from cognitive psychology was integrated into other branches of psychology and various other modern disciplines like cognitive science, linguistics, and economics.

Hindsight bias, also known as the knew-it-all-along phenomenon or creeping determinism, is the common tendency for people to perceive past events as having been more predictable than they were.

Information processing theory is the approach to the study of cognitive development evolved out of the American experimental tradition in psychology. Developmental psychologists who adopt the information processing perspective account for mental development in terms of maturational changes in basic components of a child's mind. The theory is based on the idea that humans process the information they receive, rather than merely responding to stimuli. This perspective uses an analogy to consider how the mind works like a computer. In this way, the mind functions like a biological computer responsible for analyzing information from the environment. According to the standard information-processing model for mental development, the mind's machinery includes attention mechanisms for bringing information in, working memory for actively manipulating information, and long-term memory for passively holding information so that it can be used in the future. This theory addresses how as children grow, their brains likewise mature, leading to advances in their ability to process and respond to the information they received through their senses. The theory emphasizes a continuous pattern of development, in contrast with cognitive-developmental theorists such as Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development that thought development occurs in stages at a time.

Information processing theory is the approach to the study of cognitive development evolved out of the American experimental tradition in psychology. Developmental psychologists who adopt the information processing perspective account for mental development in terms of maturational changes in basic components of a child's mind. The theory is based on the idea that humans process the information they receive, rather than merely responding to stimuli. This perspective uses an analogy to consider how the mind works like a computer. In this way, the mind functions like a biological computer responsible for analyzing information from the environment. According to the standard information-processing model for mental development, the mind's machinery includes attention mechanisms for bringing information in, working memory for actively manipulating information, and long-term memory for passively holding information so that it can be used in the future. This theory addresses how as children grow, their brains likewise mature, leading to advances in their ability to process and respond to the information they received through their senses. The theory emphasizes a continuous pattern of development, in contrast with cognitive-developmental theorists such as Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development that thought development occurs in stages at a time.

Age-related memory loss, sometimes described as "normal aging", is qualitatively different from memory loss associated with types of dementia such as Alzheimer's disease, and is believed to have a different brain mechanism.

Metamemory or Socratic awareness, a type of metacognition, is both the introspective knowledge of one's own memory capabilities and the processes involved in memory self-monitoring. This self-awareness of memory has important implications for how people learn and use memories. When studying, for example, students make judgments of whether they have successfully learned the assigned material and use these decisions, known as "judgments of learning", to allocate study time.

Autobiographical memory (AM) is a memory system consisting of episodes recollected from an individual's life, based on a combination of episodic and semantic memory. It is thus a type of explicit memory.

Emotion can have a powerful effect on humans and animals. Numerous studies have shown that the most vivid autobiographical memories tend to be of emotional events, which are likely to be recalled more often and with more clarity and detail than neutral events.

In psychology, mental time travel is the capacity to mentally reconstruct personal events from the past as well as to imagine possible scenarios in the future. The term was coined by Thomas Suddendorf and Michael Corballis, building on Endel Tulving's work on episodic memory.

Effects of alcohol on memory include disruption of various memory processes, affecting both formation and recall of information.

Foresight is the ability to predict, or the action of predicting, what will happen or what is needed in the future. Studies suggest that much of human thought is directed towards potential future events. Because of this, the nature and evolution of foresight is an important topic in psychology. Thinking about the future is studied under the label prospection.

Autonoetic consciousness is the human ability to mentally place oneself in the past and future or in counterfactual situations, and to thus be able to examine one's own thoughts.

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembered, it would be impossible for language, relationships, or personal identity to develop. Memory loss is usually described as forgetfulness or amnesia.

Embodied cognition is the concept suggesting that many features of cognition are shaped by the state and capacities of the organism. The cognitive features include a wide spectrum of cognitive functions, such as perception biases, memory recall, comprehension and high-level mental constructs and performance on various cognitive tasks. The bodily aspects involve the motor system, the perceptual system, the bodily interactions with the environment (situatedness), and the assumptions about the world built the functional structure of organism's brain and body.

Episodic-like memory is the memory system in animals that is comparable to human episodic memory. The term was first described by Clayton & Dickinson referring to an animal's ability to encode and retrieve information about 'what' occurred during an episode, 'where' the episode took place, and 'when' the episode happened. This ability in animals is considered 'episodic-like' because there is currently no way of knowing whether or not this form of remembering is accompanied by conscious recollection—a key component of Endel Tulving's original definition of episodic memory.

Aphantasia is the inability to visualize.

Sex differences in cognition are widely studied in the current scientific literature. Biological and genetic differences in combination with environment and culture have resulted in the cognitive differences among males and females. Among biological factors, hormones such as testosterone and estrogen may play some role mediating these differences. Among differences of diverse mental and cognitive abilities, the largest or most well known are those relating to spatial abilities, social cognition and verbal skills and abilities.

Social cognitive neuroscience is the scientific study of the biological processes underpinning social cognition. Specifically, it uses the tools of neuroscience to study "the mental mechanisms that create, frame, regulate, and respond to our experience of the social world". Social cognitive neuroscience uses the epistemological foundations of cognitive neuroscience, and is closely related to social neuroscience. Social cognitive neuroscience employs human neuroimaging, typically using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Human brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct-current stimulation are also used. In nonhuman animals, direct electrophysiological recordings and electrical stimulation of single cells and neuronal populations are utilized for investigating lower-level social cognitive processes.

The forward testing effect, also known as test potentiated new learning, is a psychological learning theory which suggests that testing old information can improve learning of new information. Unlike traditional learning theories in educational psychology which have established the positive effect testing has when later attempting to retrieve the same information, the forward testing effect instead suggests that the testing experience itself possesses unique benefits which enhance the learning of new information. This memory effect is also distinct from the 'practice effect' which typically refers to an observed improvement which results from repetition and restudy, as the testing itself is considered as the catalyst for improved recall. Instead, this theory suggests that testing serves not only as a tool for assessment but as a learning tool which can aid in memory recall. The forward testing effect indicates that educators should encourage students to study using testing techniques rather than restudying information repeatedly.

Hyperphantasia is the condition of having extremely vivid mental imagery. It is the opposite condition to aphantasia, where mental visual imagery is not present. The experience of hyperphantasia is more common than aphantasia and has been described as being "as vivid as real seeing". Hyperphantasia constitutes all five senses within vivid mental imagery, although literature on the subject is dominated by "visual" mental imagery research, with a lack of research on the other four senses.