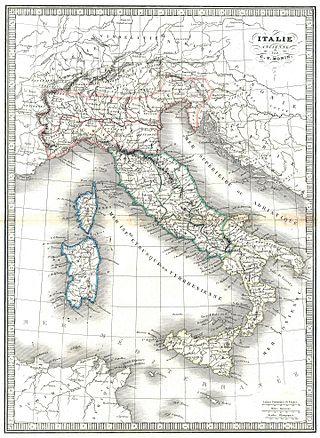

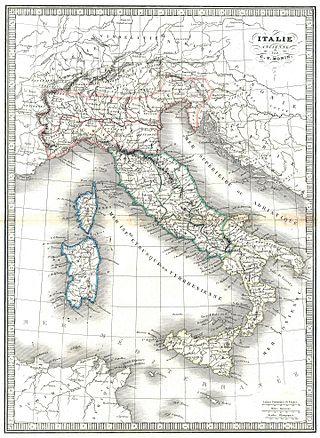

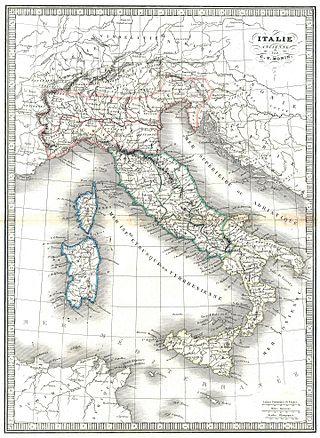

The Etruscan civilization was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in ancient Italy, with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roughly what is now Tuscany, western Umbria, and northern Lazio, as well as what are now the Po Valley, Emilia-Romagna, south-eastern Lombardy, southern Veneto, and western Campania.

The Corded Ware culture comprises a broad archaeological horizon of Europe between c. 3000 BC – 2350 BC, thus from the late Neolithic, through the Copper Age, and ending in the early Bronze Age. Corded Ware culture encompassed a vast area, from the contact zone between the Yamnaya culture and the Corded Ware culture in south Central Europe, to the Rhine on the west and the Volga in the east, occupying parts of Northern Europe, Central Europe and Eastern Europe. Early autosomal genetic studies suggested that the Corded Ware culture originated from the westward migration of Yamnaya-related people from the steppe-forest zone into the territory of late Neolithic European cultures; however, paternal DNA evidence fails to support this hypothesis, and it is now proposed that the Corded Ware culture evolved in parallel with the Yamnaya, with no evidence of direct male-line descent between them.

The Urnfield culture was a late Bronze Age culture of Central Europe, often divided into several local cultures within a broader Urnfield tradition. The name comes from the custom of cremating the dead and placing their ashes in urns, which were then buried in fields. The first usage of the name occurred in publications over grave sites in southern Germany in the late 19th century. Over much of Europe, the Urnfield culture followed the Tumulus culture and was succeeded by the Hallstatt culture. Some linguists and archaeologists have associated this culture with a pre-Celtic language or Proto-Celtic language family. By the end of the 2nd millennium BC, the Urnfield Tradition had spread through Italy, northwestern Europe, and as far west as the Pyrenees. It is at this time that fortified hilltop settlements and sheet‐bronze metalworking also spread widely across Europe, leading some authorities to equate these changes with the expansion of the Celts. These links are no longer accepted.

The Apennine culture is a technology complex in central and southern Italy from the Italian Middle Bronze Age. In the mid-20th century the Apennine was divided into Proto-, Early, Middle and Late sub- phases, but now archaeologists prefer to consider as "Apennine" only the ornamental pottery style of the later phase of Middle Bronze Age (BM3). This phase is preceded by the Grotta Nuova facies and by the Protoapennine B facies and succeeded by the Subapennine facies of 13th-century. Apennine pottery is a burnished ware incised with spirals, meanders and geometrical zones, filled with dots or transverse dashes. It has been found on Ischia island in association with LHII and LHIII pottery and on Lipari in association with LHIIIA pottery, which associations date it to the Late Bronze Age as it is defined in Greece and the Aegean.

The Kurgan hypothesis is the most widely accepted proposal to identify the Proto-Indo-European homeland from which the Indo-European languages spread out throughout Europe and parts of Asia. It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). The term is derived from the Turkic word kurgan (курга́н), meaning tumulus or burial mound.

The Tumulus culture was the dominant material culture in Central Europe during the Middle Bronze Age.

The Villanovan culture, regarded as the earliest phase of the Etruscan civilization, was the earliest Iron Age culture of Italy. It directly followed the Bronze Age Proto-Villanovan culture which branched off from the Urnfield culture of Central Europe. The name derives from the locality of Villanova, a fraction of the municipality of Castenaso in the Metropolitan City of Bologna where, between 1853 and 1855, Giovanni Gozzadini found the remains of a necropolis, bringing to light 193 tombs, of which there were 179 cremations and 14 inhumations.

The Basarabi culture was an archaeological culture in Southeastern Europe, dated between 8th - 7th centuries BC. It was named after Basarabi, a village in Dolj County, south-western Romania, nowadays an administrative component of the Calafat municipality. It is sometimes grouped with related Bosut culture, into the Bosut-Basarabi complex.

The Italic peoples were an ethnolinguistic group identified by their use of Italic languages, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

Terramare, terramara, or terremare is a technology complex mainly of the central Po valley, in Emilia, Northern Italy, dating to the Middle and Late Bronze Age c. 1700–1150 BC. It takes its name from the "black earth" residue of settlement mounds. Terramare is from terra marna, "marl-earth", where marl is a lacustrine deposit. It may be any color but in agricultural lands it is most typically black, giving rise to the "black earth" identification of it. The population of the terramare sites is called the terramaricoli. The sites were excavated exhaustively in 1860–1910.

The Golasecca culture was a Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age culture in northern Italy, whose type-site was excavated at Golasecca in the province of Varese, Lombardy, where, in the area of Monsorino at the beginning of the 19th century, Abbot Giovanni Battista Giani made the first findings of about fifty graves with pottery and metal objects.

In Europe, the Iron Age is the last stage of the prehistoric period and the first of the protohistoric periods, which initially meant descriptions of a particular area by Greek and Roman writers. For much of Europe, the period came to an abrupt end after conquest by the Romans, though ironworking remained the dominant technology until recent times. Elsewhere, the period lasted until the early centuries AD, and either Christianization or a new conquest in the Migration Period. Iron working was introduced to Europe in the late 11th century BC, probably from the Caucasus, and slowly spread northwards and westwards over the succeeding 500 years. For example, the Iron Age of Prehistoric Ireland begins around 500 BC, when the Greek Iron Age had already ended, and finishes around 400 AD. The use of iron and iron-working technology became widespread concurrently in Europe and Asia.

The prehistory of Italy began in the Paleolithic period, when species of Homo colonized the Italian territory for the first time, and ended in the Iron Age, when the first written records appeared in Italy.

The Este culture or Atestine culture was an Iron Age archaeological culture existing from the late Italian Bronze Age to the Roman period. It was located in the present territory of Veneto in Italy and derived from the earlier and more extensive Proto-Villanovan culture. It is also called "civilization of situlas", or Paleo-Venetic.

In classical antiquity, several theses were elaborated on the origin of the Etruscans from the 5th century BC, when the Etruscan civilization had been already established for several centuries in its territories, that can be summarized into three main hypotheses. The first is the autochthonous development in situ out of the Villanovan culture, as claimed by the Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus who described the Etruscans as indigenous people who had always lived in Etruria. The second is a migration from the Aegean sea, as claimed by two Greek historians: Herodotus, who described them as a group of immigrants from Lydia in Anatolia, and Hellanicus of Lesbos who claimed that the Tyrrhenians were the Pelasgians originally from Thessaly, Greece, who entered Italy at the head of the Adriatic sea in Northern Italy. The third hypothesis was reported by Livy and Pliny the Elder, and puts the Etruscans in the context of the Rhaetian people to the north and other populations living in the Alps.

The Latial culture ranged approximately over ancient Old Latium. The Iron Age Latial culture coincided with the arrival in the region of a people who spoke Old Latin. The culture was likely therefore to identify a phase of the socio-political self-consciousness of the Latin tribe, during the period of the kings of Alba Longa and the foundation of the Roman Kingdom.

The Latins, sometimes known as the Latials or Latians, were an Italic tribe which included the early inhabitants of the city of Rome. From about 1000 BC, the Latins inhabited the small region known to the Romans as Old Latium, that is, the area between the river Tiber and the promontory of Mount Circeo 100 km (62 mi) southeast of Rome. Following the Roman expansion, the Latins spread into the Latium adiectum, inhabited by Osco-Umbrian peoples.

The genetic history of Italy is greatly influenced by geography and history. The ancestors of Italians were mostly Indo-European speaking peoples and pre-Indo-European speakers. During the Roman empire, the Italian peninsula attracted people from various regions of the Mediterranean basin, including Southern Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Based on DNA analysis, there is evidence of ancient regional genetic substructure and continuity within modern Italy dating to the pre-Roman and Roman periods.

The Unstrut culture was part of the Bronze Age Urnfield culture, a homogeneous society noted for their biconical funerary urns used in storing the ashes of the deceased. The Unstrut group settled in Germany, particularly in the central region where the Saale mouth group also lived. These two groups, along with the Helmsdorf or Elb-Havel group formed on the western edge of the Lausitz culture.