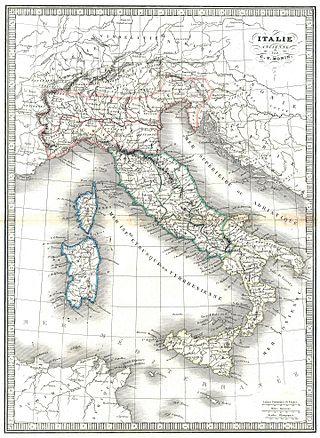

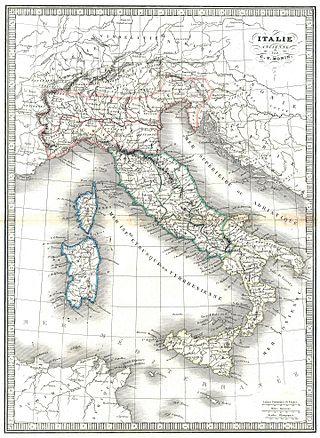

The Etruscan civilization was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in ancient Italy, with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roughly what is now Tuscany, western Umbria, and northern Lazio, as well as what are now the Po Valley, Emilia-Romagna, south-eastern Lombardy, southern Veneto, and western Campania.

The founding of Rome was a prehistoric event or process later greatly embellished by Roman historians and poets. Archaeological evidence indicates that Rome developed from the gradual union of several hilltop villages during the Final Bronze Age or early Iron Age. Prehistoric habitation of the Italian Peninsula occurred by 48,000 years ago, with the area of Rome being settled by around 1600 BC. Some evidence on the Capitoline Hill possibly dates as early as c. 1700 BC and the nearby valley that later housed the Roman Forum had a developed necropolis by at least 1000 BC. The combination of the hilltop settlements into a single polity by the later 8th century BC was probably influenced by the trend for city-state formation emerging from ancient Greece.

Veii was an important ancient Etruscan city situated on the southern limits of Etruria and 16 km (9.9 mi) north-northwest of Rome, Italy. It now lies in Isola Farnese, in the comune of Rome. Many other sites associated with and in the city-state of Veii are in Formello, immediately to the north. Formello is named after the drainage channels that were first created by the Veians.

Etruscan religion comprises a set of stories, beliefs, and religious practices of the Etruscan civilization, heavily influenced by the mythology of ancient Greece, and sharing similarities with concurrent Roman mythology and religion. As the Etruscan civilization was gradually assimilated into the Roman Republic from the 4th century BC, the Etruscan religion and mythology were partially incorporated into ancient Roman culture, following the Roman tendency to absorb some of the local gods and customs of conquered lands. The first attestations of an Etruscan religion can be traced back to the Villanovan culture.

The Falisci were an Italic tribe who lived in what is now northern Lazio, on the Etruscan side of the Tiber River. They spoke an Italic language, Faliscan, closely related to Latin. Originally a sovereign state, politically and socially they supported the Etruscans, joining the Etruscan League. This conviction and affiliation led to their ultimate near destruction and total subjugation by Rome.

The Villanovan culture, regarded as the earliest phase of the Etruscan civilization, was the earliest Iron Age culture of Italy. It directly followed the Bronze Age Proto-Villanovan culture which branched off from the Urnfield culture of Central Europe. The name derives from the locality of Villanova, a fraction of the municipality of Castenaso in the Metropolitan City of Bologna where, between 1853 and 1855, Giovanni Gozzadini found the remains of a necropolis, bringing to light 193 tombs, of which there were 179 cremations and 14 inhumations.

The concept of Italic peoples is widely used in linguistics and historiography of ancient Italy. In a strict sense, commonly used in linguistics, it refers to the Osco-Umbrians and Latino-Faliscans, speakers of the Italic languages, a subgroup of the Indo-European language family. In a broader sense, commonly used in historiography, all the ancient peoples of Italy are referred to as Italic peoples, including those who did not speak Indo-European languages such the Rhaetians, Ligures and Etruscans. As the Latins achieved a dominant position among these tribes, by virtue of the expansion of the Roman civilization, the other Italic tribes adopted Latin language and culture as part of the process of Romanization.

Caere is the Latin name given by the Romans to one of the larger cities of southern Etruria, the modern Cerveteri, approximately 50–60 kilometres north-northwest of Rome. To the Etruscans it was known as Cisra, to the Greeks as Agylla and to the Phoenicians as 𐤊𐤉𐤔𐤓𐤉𐤀.

The Tomb of the Roaring Lions is an archaeological site at the ancient city of Veii, Italy. It is best known for its well-preserved fresco paintings of four feline-like creatures, believed by archaeologists to depict lions. The tomb is believed to be one of the oldest painted tombs in the western Mediterranean, dating back to 690 BCE. The discovery of the Tomb allowed archaeologists a greater insight into funerary practices amongst the Etruscan people, while providing insight into art movements around this period of time. The fresco paintings on the wall of the tomb are a product of advances in trade that allowed artists in Veii to be exposed to art making practices and styles of drawing originating from different cultures, in particular geometric art movements in Greece. The lions were originally assumed to be caricatures of lions – created by artists who had most likely never seen the real animal in flesh before.

Barbarano Romano is a comune (municipality) in the Province of Viterbo in the Italian region of Latium, located about 50 kilometres (31 mi) northwest of Rome and about 20 kilometres (12 mi) south of Viterbo.

The Sarcophagus of the Spouses is a tomb effigy considered one of the masterpieces of Etruscan art. The Etruscans lived in Italy between two main rivers, the Arno and the Tiber, and were in contact with the Ancient Greeks through trade, mainly during the Orientalizing and Archaic periods. The Etruscans were well known for their terracotta sculptures and funerary art, predominantly sarcophagi and urns. This sarcophagus is a late sixth-century BCE Etruscan anthropoid sarcophagus found at the Banditaccia necropolis in Caere, and is now located in the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia, Rome.

Bucchero is a class of ceramics produced in central Italy by the region's pre-Roman Etruscan population. This Italian word is derived from the Latin poculum, a drinking-vessel, perhaps through the Spanish búcaro, or the Portuguese púcaro.

Etruscan art was produced by the Etruscan civilization in central Italy between the 10th and 1st centuries BC. From around 750 BC it was heavily influenced by Greek art, which was imported by the Etruscans, but always retained distinct characteristics. Particularly strong in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terracotta, wall-painting and metalworking especially in bronze. Jewellery and engraved gems of high quality were produced.

The prehistory of Italy began in the Paleolithic period, when members of the genus Homo first inhabited what is now modern Italian territory, and ended in the Iron Age, when the first written records appeared in Italy.

In ancient Roman culture, the olla is a squat, rounded pot or jar. An olla would be used primarily to cook or store food, hence the word "olla" is still used in some Romance languages for either a cooking pot or a dish in the sense of cuisine. In the typology of ancient Roman pottery, the olla is a vessel distinguished by its rounded "belly", typically with no or small handles or at times with volutes at the lip, and made within a Roman sphere of influence; the term olla may also be used for Etruscan and Gallic examples, or Greek pottery found in an Italian setting.

The Latins, sometimes known as the Latials or Latians, were an Italic tribe that included the early inhabitants of the city of Rome. From about 1000 BC, the Latins inhabited the small region known to the Romans as Old Latium, the area in the Italian Peninsula between the river Tiber and the promontory of Mount Circeo 100 km (62 mi) southeast of Rome. Following the Roman expansion, the Latins spread into the Latium adiectum, inhabited by Osco-Umbrian peoples.

Narce was a Faliscan settlement in Italy located 5 kilometers south of Falerii. Its residents spoke an Italic language related to Latin. It was inhabited from the 2nd millennium to the 3rd century B.C. The ancient name of the settlement is uncertain, but it may have been called Fescennium.

The Proto-Villanovan culture was a late Bronze Age culture that appeared in Italy in the first half of the 12th century BC and lasted until the 10th century BC, part of the central European Urnfield culture system.

Etruscan architecture was created between about 900 BC and 27 BC, when the expanding civilization of ancient Rome finally absorbed Etruscan civilization. The Etruscans were considerable builders in stone, wood and other materials of temples, houses, tombs and city walls, as well as bridges and roads. The only structures remaining in quantity in anything like their original condition are tombs and walls, but through archaeology and other sources we have a good deal of information on what once existed.

Etruscan sculpture was one of the most important artistic expressions of the Etruscan people, who inhabited the regions of Northern Italy and Central Italy between about the 9th century BC and the 1st century BC. Etruscan art was largely a derivation of Greek art, although developed with many characteristics of its own. Given the almost total lack of Etruscan written documents, a problem compounded by the paucity of information on their language—still largely undeciphered—it is in their art that the keys to the reconstruction of their history are to be found, although Greek and Roman chronicles are also of great help. Like its culture in general, Etruscan sculpture has many obscure aspects for scholars, being the subject of controversy and forcing them to propose their interpretations always tentatively, but the consensus is that it was part of the most important and original legacy of Italian art and even contributed significantly to the initial formation of the artistic traditions of ancient Rome. The view of Etruscan sculpture as a homogeneous whole is erroneous, there being important variations, both regional and temporal.