Related Research Articles

Immunosuppressive drugs, also known as immunosuppressive agents, immunosuppressants and antirejection medications, are drugs that inhibit or prevent the activity of the immune system.

Henoch–Schönlein purpura (HSP), also known as IgA vasculitis, is a disease of the skin, mucous membranes, and sometimes other organs that most commonly affects children. In the skin, the disease causes palpable purpura, often with joint pain and abdominal pain. With kidney involvement, there may be a loss of small amounts of blood and protein in the urine, but this usually goes unnoticed; in a small proportion of cases, the kidney involvement proceeds to chronic kidney disease. HSP is often preceded by an infection, such as a throat infection.

Glomerulonephritis (GN) is a term used to refer to several kidney diseases. Many of the diseases are characterised by inflammation either of the glomeruli or of the small blood vessels in the kidneys, hence the name, but not all diseases necessarily have an inflammatory component.

Pemphigus is a rare group of blistering autoimmune diseases that affect the skin and mucous membranes. The name is derived from the Greek root pemphix, meaning "blister".

Carprofen is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) of the carbazole and propionic acid class that was previously for use in humans and animals but is now only available to veterinarians for prescribing as a supportive treatment for various conditions in animals. Carprofen reduces inflammation by inhibition of COX-1 and COX-2; its specificity for COX-2 varies from species to species. Marketed under many brand names worldwide, carprofen is used as a treatment for inflammation and pain, including joint pain and postoperative pain.

Strangles is a contagious upper respiratory tract infection of horses and other equines caused by a Gram-positive bacterium, Streptococcus equi. As a result, the lymph nodes swell, compressing the pharynx, larynx, and trachea, and can cause airway obstruction leading to death, hence the name strangles. Strangles is enzootic in domesticated horses worldwide. The contagious nature of the infection has at times led to limitations on sporting events.

H3N8 is a subtype of the species Influenza A virus that is endemic in birds, horses and dogs. It is the main cause of equine influenza and is also known as equine influenza virus. In 2011, it was reported to have been found in seals. Cats have been experimentally infected with the virus, leading to clinical signs, shedding of the virus and infection of other cats. In 2022 and 2023, three people in China were infected with H3N8, with one fatality, marking the first time a human has died from this strain of flu.

Equid alphaherpesvirus 4, formerly Equine herpesvirus 4 (EHV-4) is a virus of the family Herpesviridae that cause rhinopneumonitis in horses. It is the most important viral cause of respiratory infection in foals. Like other herpes viruses, EHV-4 causes a lifelong latent infection in affected animals. These horses are usually the source for new infection for foals over two months old, weanlings, and yearlings. Symptoms include fever, loss of appetite, and discharge from the nose. Most infected animals recover in one to three weeks, but death can occur in environments with overcrowding and other stress factors. There are several vaccines available.

Equid alphaherpesvirus 1, formerly Equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1), is a virus of the family Herpesviridae that causes abortion, respiratory disease and occasionally neonatal mortality in horses. Initial spread of EHV-1 by a newly introduced horse through direct and indirect contact can lead to abortion and perinatal infection in up to 70 percent of a previously unexposed herd. Abortion usually occurs in the last four months of gestation, two to four weeks after infection of the mare. Perinatal infection can lead to pneumonia and death. Encephalitis can occur in affected animals, leading to ataxia, paralysis, and death. There is a vaccine available, however its efficacy is questionable. The virus varies in severity from sub-clinical to very severe. Most horses have been infected with EHV-1, but the virus can become latent and persist without ever causing signs of infection. In 2006, an outbreak of EHV-1 among stables in Florida resulted in the institution of quarantine measures. The outbreak was determined to have originated in horses imported from Europe via New York, before being shipped to Florida.

Pemphigoid is a group of rare autoimmune blistering diseases of the skin and mucous membranes. As its name indicates, pemphigoid is similar in general appearance to pemphigus, however unlike pemphigus, pemphigoid does not feature acantholysis, a loss of connections between skin cells.

Meclofenamic acid is a drug used for joint, muscular pain, arthritis and dysmenorrhea. It is a member of the anthranilic acid derivatives class of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and was approved by the US FDA in 1980. Like other members of the class, it is a cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor, preventing the formation of prostaglandins.

Streptococcus zooepidemicus is a Lancefield group C streptococcus that was first isolated in 1934 by P. R. Edwards, and named Animal pyogens A. It is a mucosal commensal and opportunistic pathogen that infects several animals and humans, but most commonly isolated from the uterus of mares. It is a subspecies of Streptococcus equi, a contagious upper respiratory tract infection of horses, and shares greater than 98% DNA homology, as well as many of the same virulence factors.

Angina bullosa haemorrhagica is a condition of the mucous membranes characterized by the sudden appearance of one or more blood blisters within the oral cavity. The lesions, which may be caused by mild trauma to the mouth tissues such as hot foods, typically rupture quickly and heal without scarring or further discomfort. The condition is not serious except in rare cases where a large bulla that does not rupture spontaneously may cause airway obstruction.

Guttural pouches are large, auditory-tube diverticula that contain between 300 and 600 ml of air. They are present in odd-toed mammals, some bats, hyraxes, and the American forest mouse. They are paired bilaterally just below the ears, behind the skull and connect to the nasopharynx.

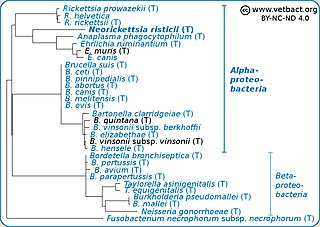

Neorickettsia risticii, formerly Ehrlichia risticii, is an obligate intracellular gram negative bacteria that typically lives as an endosymbiont in parasitic flatworms, specifically flukes. N. risticii is the known causative agent of equine neorickettsiosis, which gets its name from its discovery near the Potomac River in Maryland and Virginia. N. risticii was first recovered from horses in this region in 1984 but was not recognized as the causative agent of PHF until 1979. Potomac horse fever is currently endemic in the United States but has also been reported with lower frequency in other regions, including Canada, Brazil, Uruguay, and Europe. PHF is a condition that is clinically important for horses since it can cause serious signs such as fever, diarrhea, colic, and laminitis. PHF has a fatality rate of approximately 30%, making this condition one of the concerns for horse owners in endemic regions N. risticii is typically acquired in the middle to late summer near freshwater streams or rivers, as well as on irrigated pastures. This is a seasonal infection because it relies on the ingestion of an arthropod vector, which is more commonly found on pasture in the summer months. Although N. risticii is a well known causative agent for PHF in horses, it may act as a potential pathogen in cats and dogs as well. Not only has N. risticii been successfully cultured from monocytes of dogs and cats, but cats have become clinically ill after experimental infection with the bacteria. In addition, N. risticii has been isolated and cultured from human histiocytic lymphoma cells.

Pigeon fever is a disease of horses, also known as dryland distemper or equine distemper, caused by the Gram-positive bacteria Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis biovar equi. Infected horses commonly have swelling in the chest area, making it look similar to a "pigeon chest". This disease is common in dry areas. Pigeon fever is sometimes confused with strangles, another infection that causes abscesses.

Theiler's disease is a viral hepatitis that affects horses. It is one of the most common cause of acute hepatitis and liver failure in the horse.

Grapiprant, sold under the brand name Galliprant, is a small molecule drug that belongs in the piprant class. This analgesic and anti-inflammatory drug is primarily used as a pain relief for mild to moderate inflammation related to osteoarthritis in dogs. Grapiprant has been approved by the FDA's Center for Veterinary Medicine and was categorized as a non-cyclooxygenase inhibiting non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) in March 2016.

Streptococcosis is an infectious disease caused by bacteria of the genus Steptococcus. This disease is most common among horses, guinea pigs, dogs, cats, and fish with symptoms varying based on the streptococcal species involved. In humans, this disease typically involves a throat infection and is called streptococcal pharyngitis or strep throat.

References

- 1 2 "Strangles - Complications".

- 1 2 3 4 MacLeay, JM (February 2000). "Purpura hemorrhagica". Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 20 (2): 101. doi:10.1016/S0737-0806(00)80451-7.

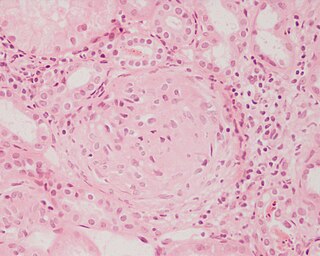

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pusterla, N; Watson, JL; Affolter, VK; Magdesian, KG; Wilson, WD; Carlson, GP (26 July 2003). "Purpura haemorrhagica in 53 horses". The Veterinary Record. 153 (4): 118–21. doi:10.1136/vr.153.4.118. PMID 12918829. S2CID 32178046.

- ↑ Kaese, HJ; Valberg, SJ; Hayden, DW; Wilson, JH; Charlton, P; Ames, TR; Al-Ghamdi, GM (1 June 2005). "Infarctive purpura hemorrhagica in five horses". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 226 (11): 1893–8, 1845. doi:10.2460/javma.2005.226.1893. PMID 15934258.

- 1 2 Taylow, S. D.; Wilson, W. D. (September 2006). "Streptococcus equi subsp. equi (Strangles) Infection". Clinical Techniques in Equine Practice. 5 (3): 211–217. doi:10.1053/j.ctep.2006.03.016.